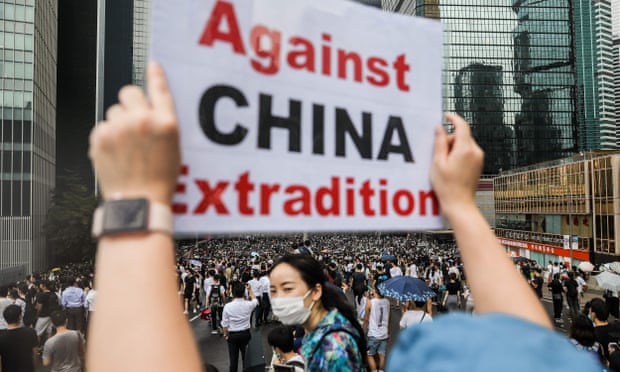

Chinese authorities and masked protesters have held rival press conferences in an attempt to take control of the narrative amid escalating demonstrations in Hong Kong.

In a rare press conference on Tuesday, Beijing sounded its strongest warning yet to protesters not to underestimate the power of the Chinese government.

Calling the demonstrators “brazen, violent and criminal actors”, Yang Guang, a spokesman for the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the Chinese government, said: “Don’t misjudge the situation or take restraint as a sign of weakness … don’t underestimate the firm resolve and tremendous power by the central government.”

Quick GuideWhat are the Hong Kong protests about?

Show

Why are people protesting?

The protests were triggered by a controversial bill that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China, where the Communist party controls the courts, but have since evolved into a broader pro-democracy movement.

Public anger – fuelled by the aggressive tactics used by the police against demonstrators – has collided with years of frustration over worsening inequality and the cost of living in one of the world's most expensive, densely populated cities.

The protest movement was given fresh impetus on 21 July when gangs of men attacked protesters and commuters at a mass transit station – while authorities seemingly did little to intervene.

Underlying the movement is a push for full democracy in the city, whose leader is chosen by a committee dominated by a pro-Beijing establishment rather than by direct elections.

Protesters have vowed to keep their movement going until their core demands are met, such as the resignation of the city’s leader, Carrie Lam, an independent inquiry into police tactics, an amnesty for those arrested and a permanent withdrawal of the bill.

Lam announced on 4 September that she was withdrawing the bill.

Why were people so angry about the extradition bill?

Beijing’s influence over Hong Kong has grown in recent years, as activists have been jailed and pro-democracy lawmakers disqualified from running or holding office. Independent booksellers have disappeared from the city, before reappearing in mainland China facing charges.

Under the terms of the agreement by which the former British colony was returned to Chinese control in 1997, the semi-autonomous region was meant to maintain a “high degree of autonomy” through an independent judiciary, a free press and an open market economy, a framework known as “one country, two systems”.

The extradition bill was seen as an attempt to undermine this and to give Beijing the ability to try pro-democracy activists under the judicial system of the mainland.

How have the authorities responded?

Beijing has issued increasingly shrill condemnations but has left it to the city's semi-autonomous government to deal with the situation. Meanwhile police have violently clashed directly with protesters, repeatedly firing teargas and rubber bullets.

Beijing has ramped up its accusations that foreign countries are “fanning the fire” of unrest in the city. China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi has ordered the US to “immediately stop interfering in Hong Kong affairs in any form”.

Lily Kuo and Guardian reporter in Hong Kong

Yang responded to questions about whether Beijing would deploy its military in Hong Kong by reiterating the Chinese government’s support of Hong Kong’s leader, Carrie Lam. Yang said that with the backing of the Chinese government and the people of China, the Hong Kong government and police were “fully capable of punishing those criminal activities and restoring order”.

Yet, across the border in the city of Shenzhen, police took part in riot training in footage released by the state-run Global Times on Tuesday. Officers faced people dressed in black and wearing colourful hard hats – outfits that evoked those worn by Hong Kong protesters – throwing petrol bombs, pushing a trolley on fire towards police, and hitting officers with wooden sticks.

Earlier on Tuesday, masked protesters staged their first “civilian press conference”, in response to government and police press briefings.

“Netizens have initiated the citizens’ press conference, to bring the people’s unheard voice to the public and to highlight the repeated condemnations and empty rhetoric presented by the [Hong Kong] government,” said an unidentified speaker wearing a yellow hard hat, accompanied by a sign language translator.

The dual press conferences took place a day after some of the worst confrontations between protesters and police, who clashed in at least seven districts of the semi-autonomous city. Police fired teargas and rubber bullets at protesters who occupied roads and vandalised police stations and arrested 148 people aged between 13 and 63 on suspicion of assault and possession of offensive weapons.

Hong Kong, in its ninth week of consecutive mass protests, is facing its most serious political crisis since the former British colony was returned to Chinese control in 1997.

Like much of the protest movement, the demonstrators’ press gathering was organised on the online forum LIHKG, the city’s version of Reddit, and those speaking sought to make it clear they had no political or organisational affiliation, and did not represent all the protesters. It came after Lam on Monday announced the police would hold daily press conferences.

One of the group’s first orders of business was to provide a counter-narrative to claims by the Hong Kong government that the economic slowdown was due to the protests, instead placing the blame squarely on global economic problems.

Later, the speakers reiterated the five demands of the protesters, called for a return of “power back to the people”, and said the “pursuit of democracy” was “the inalienable right of the people”.

Quick GuideDemocracy under fire in Hong Kong since 1997

Show

Hong Kong’s democratic struggles since 1997

1 July 1997: Hong Kong, previously a British colony, is returned to China under the framework of “one country, two systems”. The “Basic Law” constitution guarantees to protect, for the next 50 years, the democratic institutions that make Hong Kong distinct from Communist-ruled mainland China.

2003: Hong Kong’s leaders introduce legislation that would forbid acts of treason and subversion against the Chinese government. The bill resembles laws used to charge dissidents on the mainland. An estimated half a million people turn out to protest against the bill. As a result of the backlash, further action on the proposal is halted.

2007: The Basic Law stated that the ultimate aim was for Hong Kong’s voters to achieve a complete democracy, but China decides in 2007 that universal suffrage in elections for the chief executive cannot be implemented until 2017. Some lawmakers are chosen by business and trade groups, while others are elected by vote. In a bid to accelerate a decision on universal suffrage, five lawmakers resign. But this act is followed by the adoption of the Beijing-backed electoral changes, which expand the chief executive’s selection committee and add more seats for lawmakers elected by direct vote. The legislation divides Hong Kong's pro-democracy camp, as some support the reforms while others say they will only delay full democracy while reinforcing a structure that favors Beijing.

2014: The Chinese government introduces a bill allowing Hong Kong residents to vote for their leader in 2017, but with one major caveat: the candidates must be approved by Beijing. Pro-democracy lawmakers are incensed by the bill, which they call an example of “fake universal suffrage” and “fake democracy”. The move triggers a massive protest as crowds occupy some of Hong Kong’s most crowded districts for 70 days. In June 2015, Hong Kong legislators formally reject the bill, and electoral reform stalls. The current chief executive, Carrie Lam, widely seen as the Chinese Communist party’s favoured candidate, is hand-picked in 2017 by a 1,200-person committee dominated by pro-Beijing elites.

2019: Lam pushes amendments to extradition laws that would allow people to be sent to mainland China to face charges. The proposed legislation triggers a huge protest, with organisers putting the turnout at 1 million, and a standoff that forces the legislature to postpone debate on the bills. After weeks of protest, often meeting with violent reprisals from the Hong Kong police, Lam announced that she would withdraw the bill.

News of Monday’s violence filtered into mainland China, where censors have been allowing more discussion of the protests, framed as riots.

On the social media platform Weibo the hashtag #FujianFellows was trending alongside videos of men in white grabbing long bamboo sticks to beat protesters and “protect ordinary neighbours”. Their attack on protesters was reminiscent of a more brutal attack by men similarly dressed in white on 21 July in and around a subway train station in the district of Yuen Long, in which at least 45 people were injured.

The US House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, issued a statement in support of the protesters: “The people of Hong Kong are sending a stirring message to the world: the dreams of freedom, justice and democracy can never be extinguished by injustice and intimidation.”

She said their courage was extraordinary while Hong Kong’s government was “cowardly”, and said it was refusing to respect the rule of law and called for it to meet the Hongkongers’ legitimate democratic aspirations.

China’s foreign ministry released a statement on Tuesday rebuking Pelosi, saying her words and that of others in support of Hong Kong’s protesters had made the demonstrators “even more fearless and lawless”.