Why China’s overseas students find things aren’t always better back home

More Chinese than ever before are studying overseas, but when they return many struggle to find jobs that satisfy their high aspirations

Having obtained a dual bachelor’s degree from a US university and climbed to a senior software engineer’s position within two and a half years of working for an American company, Owen Wang was forced to dramatically scale back his salary expectations when he decided to come home to China.

Currently working in Kansas City – where the average annual senior software engineer’s salary is US$100,000, according to glassdoor.com – the best offer from a Chinese firm he has received so far is a package from a Shenzhen-based start-up worth around 240,000 yuan (US$35,250).

But while he had expected salaries in the southern Chinese city to be lower than those on offer in the US – the per capita income in Kansas City is over four times more than the average in Shenzhen – he had been hoping someone would offer him a pay packet worth around 500,000 yuan a year.

“We’re still negotiating. I guess I will finally accept a compromise if there’s no better choice, but the quality of my life will drop significantly,” said the 27-year-old.

Wang’s plan to return home is not motivated purely by financial considerations – he worries that tighter US immigration policies will make it harder for him to stay and his parents have been hoping that he will be able to come home and visit them more often – but his disappointment is mirrored by many of the hundreds of thousands of Chinese who return home from studying and working overseas every year.

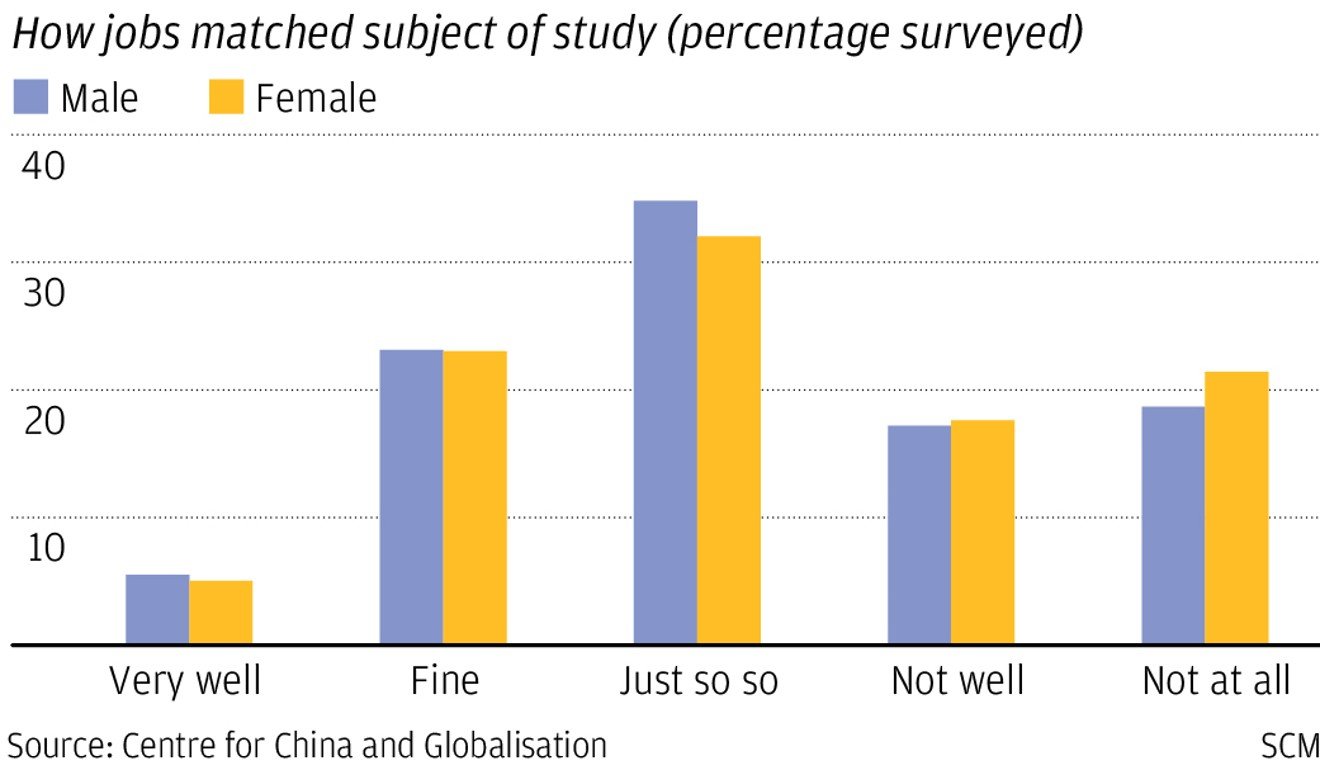

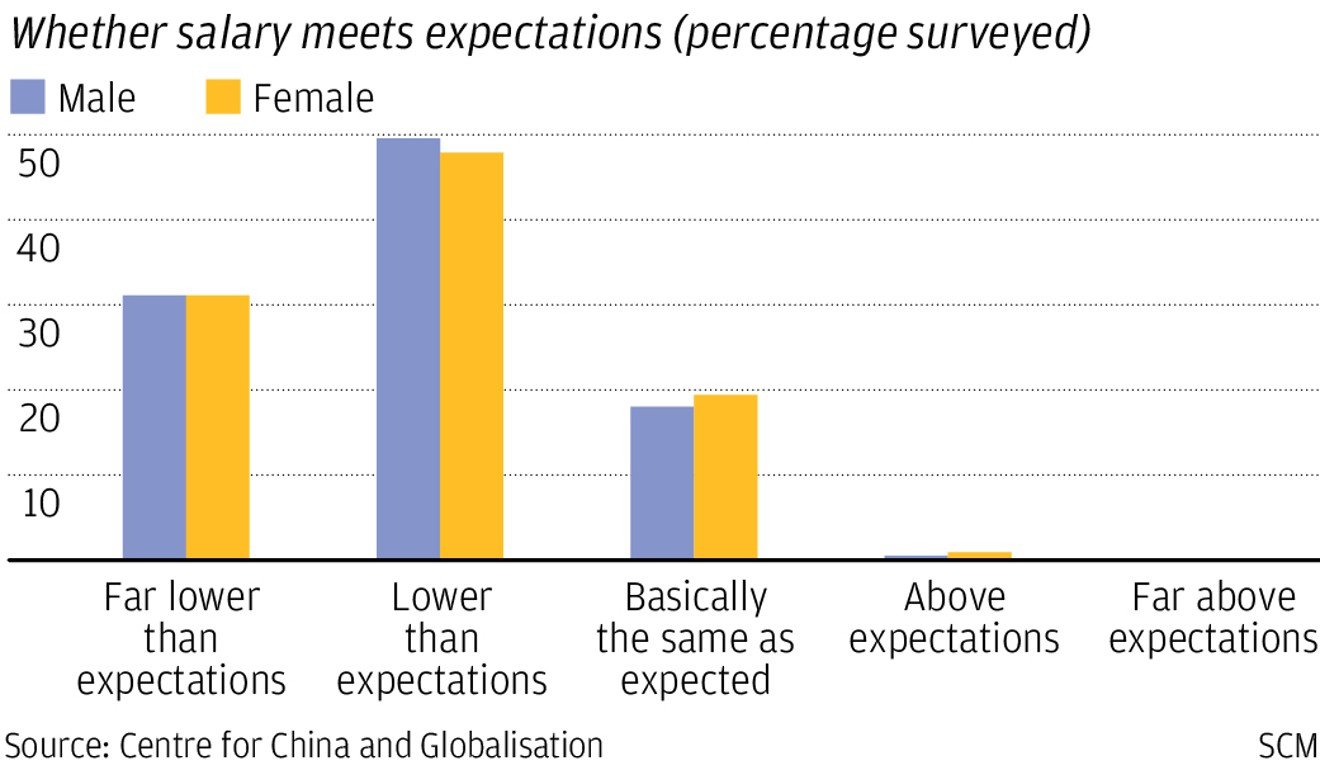

A recent survey by a Beijing-based think tank of more than 2,000 Chinese returnees found that about 80 per cent said their salaries were lower than expected, with around 70 per cent saying what they were doing did not match their experience and skills.

New firewall between Pentagon and Confucius Institutes on US campuses

“The group of overseas returnees are seeing a widening gap between their income and expectations,” said the report issued in mid August by the Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG).

While growing number of students are being sent abroad by their increasingly affluent families for what is deemed a better education in the West, a large proportion are being lured back both by personal considerations like Wang’s and the opportunities presented by a quickly growing economy.

Last year China sent 608,400 people to study abroad, up by 11 per cent from the previous year and over four times of the number 10 years ago, according to the Ministry of Education. In the same year, 480,000 returned.

Over the past four decades, about 5.2 million Chinese have gone abroad to study, more than 80 per cent of whom eventually returned, official data showed.

Chu Zhaohui, a senior researcher at the National Institute of Education, said that international academic experience used to be highly valued because only the best students were able to win places at foreign universities.

But now the growing numbers of these haigui or “sea turtles” as they are known colloquially (a word play on two similar sounding phrases) have diluted the value of this experience.

“Many of the students are sent abroad because their parents can afford it. They vary a lot in terms of diligence, intelligence, social skills, and so on,” he said.

Wang believes he is at a major disadvantage because he has lost touch with the situation in China after being based in Missouri since 2010.

“I didn’t know about my industry in China until I started asking my friends there about it half a year ago,” he said.

Although he believed his quick progression in a big US company and fluency in English made him more valuable compared with those with similar education and work experience in China, he found that major Chinese tech firms did not put a premium on his experience.

“Headhunters told me that the big firms would want to hire former employees of top companies such as Google and Facebook. As for the small ones, they cannot afford haigui,” he said.

How Chinese students who return home after studying abroad succeed – and why they don’t

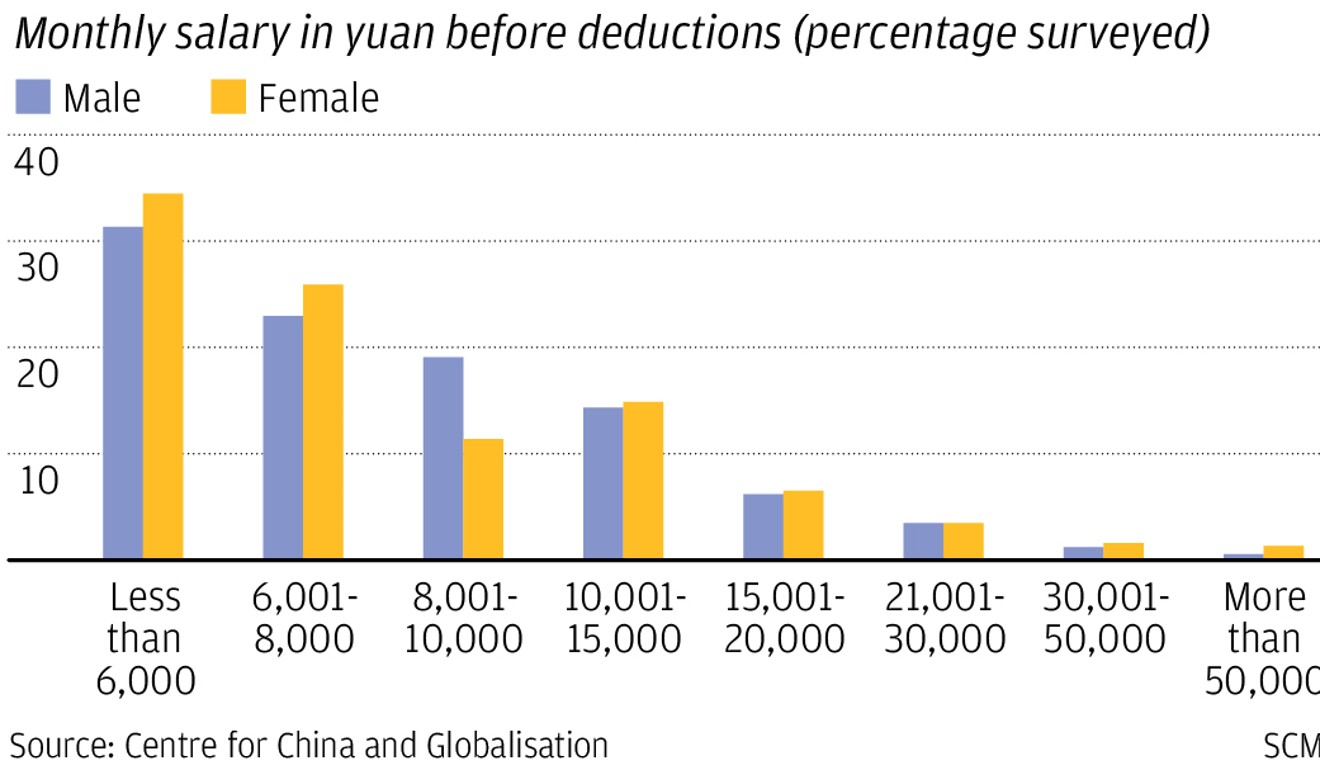

In the CCG’s survey, nearly a third of those questioned reported that their monthly salary was 10,000 yuan (US$1,470) or more, which – excluding any bonuses or other benefits – would equate to an annual salary of US$17,600 or more.

A further 40 per cent were paid between 6,000 and 10,000 yuan a month, and the rest were paid less than 6,000 yuan a month – equivalent to a basic salary of less than US$10,700 a year.

Though they are already earning more than the average graduate from domestic universities, they often expect to make more after living in higher income countries, said Nancy Zhou, who completed a one-year postgraduate programme at the University of Warwick in England early last year and then moved to Shanghai to work for an internet company.

She said although she found a satisfactory job within three months, it took longer than she expected.

One major issue for overseas students looking for a job back home is that they graduate at the wrong time of year for the main domestic graduate recruitment season, which begins in May and June for the hi-tech sector.

She also said that the lack of internships and the “reverse culture shock” experienced when readjusting to life in China also hampered returnees.

“For example, I’m not good at those skills required in a nepotistic society [like China],” Zhou said.

She explained some of the expected forms of networking and currying favour with employers made her feel uncomfortable, for example the heavy drinking culture at business dinners.

“You know on such occasions people will often be forced to drink and it’s considered rude if you refuse,” she said.

But despite their complaints, the growing supply of talent educated overseas is making a great contribution to Chinese society, said Wang Huiyao, director of the CCG.

They are playing a key role in China’s innovation and entrepreneurship after joining emerging industries or choosing to start up their own businesses after coming back, he noted.

“I would say that those people were a catalyst for innovation in China in recent years. For example, because of their contribution, new things have come thick and fast in China’s internet sector,” he said.

“With a great number of both people leaving for study overseas and people returning, China is now witnessing a virtuous cycle [in talent supply],” he added.

Double degree: Shanghai twins both headed for MIT to study theoretical physics

However, the CCG report warned that employers had to do more to address the widespread discontent among haigui – the percentage switching jobs because they were unsatisfied with their salaries rose by around 9 points compared with the previous year – if they hoped to retain talent.

Various local authorities have also set up incentives to lure haigui to their areas, ranging from easier access to residency rights to discounted housing or cash bonuses.

But the survey found 60 per cent of those questioned were not fully aware of these incentives and it recommended that more should be done to advertise these.