“When you think of hip-hop blogs, you think of us.” —LowKey, YouHeardThatNew

In 2009, Vibe magazine closed its doors, marking the end of an era. Founded by Quincy Jones and Time Warner in 1992, the magazine became a source for widely celebrated, award-winning journalism, and propelled the careers of everyone from 2Pac to Mariah Carey. Although Vibe was damaged by the recession and a stumbling music industry, its subscription numbers were solid. But the Internet caused the rates for print advertising to decline precipitously. The lower rates for online advertising didn't make up the difference, so few publications were willing to make the jump and invest fully in a web-driven direction. Established, undernourished websites like SOHH and AllHipHop moved sluggishly to fill the void, perhaps not recognizing the opportunity before them. More than other genres, hip-hop has a constant churn of news and music—diss tracks, rumors, radio freestyles, and illicit mixtapes have long been the culture's hidden backbone, flourishing outside the market of radio singles and major label albums. Likewise, the nonstop drip-drip-drip of music leaks had become a flood. With the music industry helpless to stop up the dam, the genre had a massive, invested audience, a surplus of product, and no platform.

This was the empty space a new generation of personalities and enthusiasts clambered to fill. And soon business was booming. As more and more readers shifted to the Internet for daily news and music, there was a huge opportunity to shape the conversation—and few magazines aggressively pursuing online audiences. In their place grew an ad hoc collection of independent hip-hop blogs, which rose in influence disproportionate to their small size, when compared with the fully-staffed magazines that came before them. In 2008, while print media foundered, seven of the biggest brand names in hip-hop blogging came together to form the New Music Cartel, whose members became the gatekeepers in a new era for hip-hop media: 2DopeBoyz, OnSmash, YouHeardThatNew, Xclusives Zone, Miss Info, DaJaz1, and the father of them all, NahRight. In the process, some bloggers became, for a brief window, rich.

“Nothing goes down unless we’re involved,” NahRight founder Ahsmi “Eskay” Rawlins stunted when christening the group on May 6, 2008. “No exclusives, no singles, no nothing. A freestyle is spit in the park, we want in. You guys got fat while everybody starved on the street. It’s our turn.” The “you guys” linked in the text included iTunes, the Recording Industry Association of America, New York radio superpower Hot 97, and mixtape DJ Big Mike. Despite its seemingly innocuous context, at the time it was a bold statement about the arrival of a new player in the distribution of hip-hop music and news.

What was the NMC? During the NMC's heyday—roughly 2008–2011—the crew served a few different functions, depending on who you asked. Sometimes it was a professional support network. It was also a strategic alliance in the battle for exclusives with bigger brands, a platform for giving a leg up to rising artists, a crew of leakers profiting from others' intellectual property, an email listserv of daily chit-chat and pornographic images. But inarguably it was a group of pioneers building an audience and growing rapidly at a time when media and music industries alike were in freefall.

MP3 blogs had become a media phenomenon a few years prior; in 2004, Rolling Stone highlighted the “music blog boom,” touting Fluxblog's 2,500 daily unique views. At that time, the pace was glacial, and celebrated bloggers were writers first and foremost—RS observed Oliver Wang painstakingly ripping old soul records for daily posts and described the Cocaine Blunts hip-hop blog’s “overbearing critical swagger...redeemed by great taste.” Although a few of these first-wave music blogs covered hip-hop, the hip-hop blog as it became known by the end of the decade was created by Eskay on nahright.com in May 2005 and perfected within the next two years. Simple and straightforward, his template became the baseline upon which the hip-hop blogosphere, and ultimately hip-hop media more broadly, was built.

“Consistency and speed,” says Brendan “BFred” Frederick, former VP of operations at Complex and genius.com’s director of content, when describing the reasons for NahRight’s success. “But they also had a subtle taste that they messaged with the things that they chose to write about.” Frederick was responsible for hiring Eskay to run XXL’s web presence in late 2006 after following NahRight’s sudden rise. “It’s a basic site, which was what was so good about it—it didn’t try to be fancy. It gave it to you, fastball down the middle: Here’s the new stuff.”

Ahsmi Rawlins was born in New York City in 1977 and moved to Yonkers, N.Y., when he was still a kid. His first exposure to hip-hop came in the mid-’80s through MTV and WNYC’s Video Music Box, where he discovered Run-DMC. In the early 2000s, while working as a desktop support analyst for a New York publishing company, he came across hiphopmusic.com, the hip-hop blog of writer, critic, and radio DJ Jay Smooth. It sparked an idea: “I was burning CDs for people, emailing them to people. I saw [NahRight] as a place to bring all that together, this central location for people I knew to find music—and also to make it available to whoever else might be interested.”

When starting the site, Rawlins reinvented himself as a mysterious figure named Eskay. The name derived from Rawlins’ graffiti handle as a teenager: SK. The pseudonym was necessary mainly because he was doing most of his blogging in the office at his day job. He quickly honed a straightforward blogging style: summaries of news that would interest a hip-hop audience with brief, measured editorializing, links to other hip-hop sites and stories of note, and—most notably—new leaked MP3s.

“That was the point where the labels realized they needed to start paying attention to what we were doing." —eskay

And no doubt many came mainly for the music. Eskay lived in the legal gray area in which all MP3 sites existed at the time. At that early point, his source for new music was message boards—leaks appeared in public web forums, and Eskay posted them to NahRight. In centralizing this music, his site rapidly inverted the message board dynamic—soon, his comments section became a community of its own, regularly spawning lengthy discussions that veered far from the original song or video at the top of the post.

NahRight wasn’t a financial success—at the time, it was making mere pennies via Google AdSense—but its popularity was undeniable, and other sites began to attract similar attention. One was 2DopeBoyz. While NahRight played to a primarily New York-oriented hip-hop audience with a street edge, 2DopeBoyz had more of a true school vibe. Founded by Californians Joel “Shake” Zela and Meka Udoh, the site also had a West Coast orientation.

Initially—as with most blogs—it started out as a hobby. “We were just going to put out music we enjoy,” Meka says. “Within the first month we had maybe 12,000 hits. The next month we got 25,000 hits. The months [following] it just kept doubling and doubling.” The democratization of publishing found hip-hop fans pushing against marketing categories to which they’d felt assigned. “I honestly thought I was one of the few people out there who enjoyed both Mos Def and Cam’ron. And it turned out a lot of people were also huge fans. I just thought it was always interesting people could like Sean Price and Cam’ron in the same breath.”

The other blogs that became a part of the NMC soon followed. Splash, a Queens blogger who came up alongside mixtape DJs Envy and Clue, founded DaJaz1 in 2008. For Eskay, he served as a mentor. “He’s the OG New York mixtape head,” says Eskay. “Anything that has to do with mixtapes that happened in New York City between 1992 and now, Splash knows it.”

Meanwhile, Xclusives Zone, founded in 2008, was about hitting everything, and fast. At the time, it was the connoisseur’s haunt, with virtually no editorial concerns. Less a tastemaker than a running catalog of hip-hop released during that era, it was helmed by the enigmatic Mr. X, about whom no one—including the other members of the NMC—seems to know much. “He was just so quick,” says Eskay. “He’s always got his eyes and ears open. I don’t even know how he does it.”

But perhaps no site in the NMC better had its finger on the pulse of where hip-hop, popular music, and technology would go than OnSmash, founded in 2006 by label employee named Kevin "Hof" Hofman. “OnSmash had a good ear for things that were gonna become big,” Eskay says. “If you were in that rap Internet world, a lot of things would come across your plate. Especially at that point in time, OnSmash was doing a good job of saying, ‘Hey, this is gonna be big.’”

OnSmash began as a message board called DaPhatSpot in 2004. Hof worked in digital marketing for a major label and says he found the message board a huge asset to his job. “There were a lot of kids on that message board who had good intuition on what was popping at the time,” he says. “It would be a good place to help test records. The A&R staff would give me records a little early to see what the feedback was.”

“We showed how powerful we are—we’re just as powerful as the label, we’re just as powerful as a popular DJ."

—Lowkey

DaPhatSpot was a notable message board in hip-hop; some suggest it was where A$AP Yams first linked up with A$AP Ant, a Baltimorean who posted as Antman. It was also where Hof met a developer who helped him program the first OnSmash video player. “The video player came before the blog section,” Hof says. “[It] began when YouTube first started its content ID system. Rappers were now doing videos to a lot of their freestyles over beats that they didn’t have the rights to. So, they couldn’t put their videos on YouTube any more, because those videos were getting tagged by content ID. As someone who is friends with a lot of the artists, A&Rs, managers, and so forth, I’d seen a need for a kind of video site to emerge.”

The first video OnSmash posted was for Kanye West’s flip of Rich Boy's “Throw Some D’s,” which led to more and more artists reaching out. Hof hoped to emulate New York cable access show Video Music Box, which broadcast underground hip-hop videos in the 1990s. “There was no place to get a curated list of all the hot new videos because everybody was putting their videos up on YouTube, and as we know YouTube has no curation to it. So instead of their videos getting lost in the sauce, everyone wanted to come and have their videos on our site.”

The site also began migrating street DVDs to the streaming web. Eventually, competitors popped up. One was Lee Q. O'Denat, founder of WorldStarHipHop, who claimed in a 2012 interview that OnSmash had been not just the model for his site, but implying some "savage street-hacking attacks" were involved in "creating" their own video player. Yet at the time, Hof himself claims he was largely uninterested in monetizing his platform; he continued working in the music industry while running OnSmash. “We were all fans of the music, and we were just working together to do our best to make sure the music we thought was the best at the time was going to get the proper spotlight,” he claims, “because the music we thought of as the best at the time, those artists didn’t have a proven sales history or any singles history.”

To Hof, joining the NMC was about smaller sites coming together to muscle their way up against competition coming from sites with deeper pockets for premieres, like AOL and Yahoo, and then using that muscle to give artists traction. And he was becoming exceedingly successful. OnSmash helped propel both Curren$y—the site premiered his earliest solo, post-Cash Money mixtapes—and Rick Ross at a time when their careers were in doubt. Ross shouted out OnSmash in the liner notes to 2010’s Teflon Don.

In 2008, NahRight became one of the first blogs to make a jump to the newly established Complex Media Network. At the time, the site was rap Internet's biggest source of traffic. (Ultimately, all members of the NMC signed on to the CMN.) Complex’s approach was hands-off, allowing each site to operate its content independently, while Complex sold ads against their content and shared the revenue stream.

The ad-based approach was lucrative enough that by the end of 2008, Eskay had quit XXL and was running NahRight full time while living in New York and raising a family. “Around 2009, 2010, was probably the peak of our revenue stream,” he says. “That was the point where the labels realized they needed to start paying attention to what we were doing. We were so narrowly focused, and we had the eyes and attention of the exact people that they wanted to advertise to. And they started to pour money into advertising with us.”

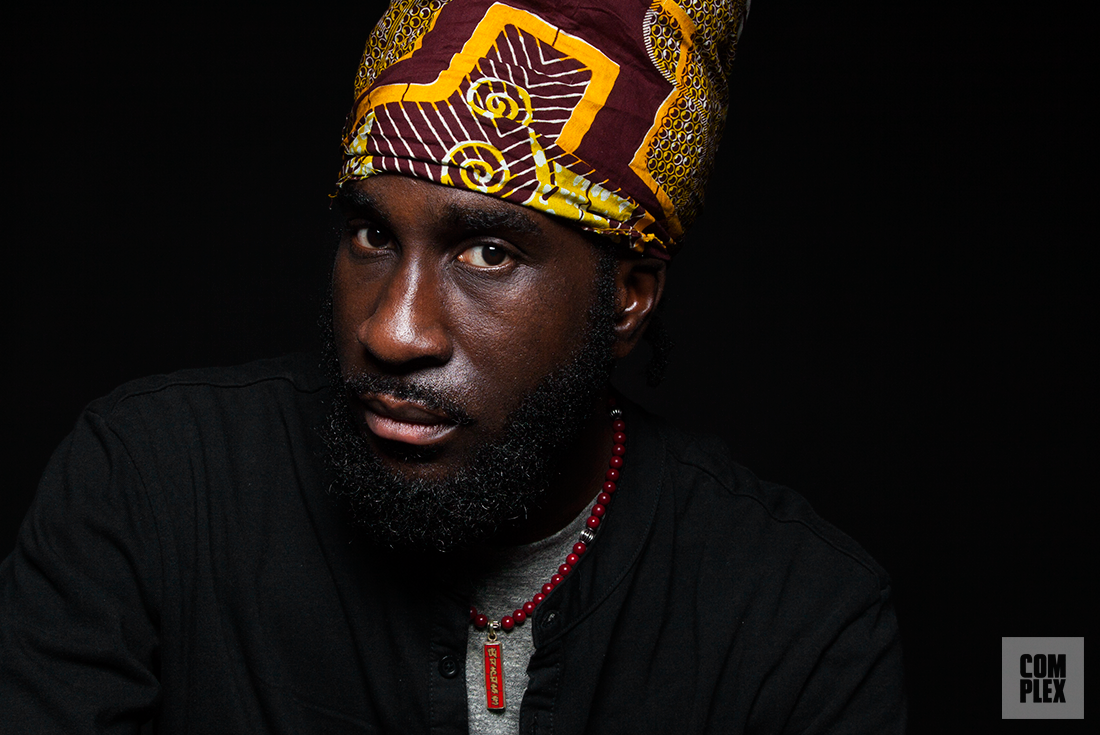

“We were ruffling feathers left and right, but we didn’t give a shit,” says Nile “LowKey” Ivey, an ironically named, chest-beating founder of the NMC site YouHeardThatNew. “We showed how powerful we are—we’re just as powerful as the label, we’re just as powerful as a popular DJ, we’re just as, if not more powerful.”

“It would be a good place to help test records. The A&R staff would give me records a little early to see what the feedback was.” —hof

The success of the NMC had a lot to do with its focus on distributing music first and foremost, and that meant providing exclusive content to which other sites—including major magazines—didn’t have access. LowKey’s YouHeardThatNew was not the biggest of the NMC sites. As the sites became more professionalized, artists, managers, and A&Rs had started to reach out to the bloggers directly, and for LowKey, it was his exclusivity set his site apart: “I started the site based on what I was obtaining,” he says. “I would have music before Eskay, I would have music before Miss Info. And that was my [contribution] to the group. Everyone had their own niche, and my own was just having music first.”

LowKey grew up in South Brunswick, N.J. His father worked for Sony Music, and LowKey interned at Sony Music Studios in high school, hoping to become a producer or engineer. While attending Howard University, he interned for Puff Daddy. After graduating in 2006, he hoped to work in radio, but sending out air checks to different radio stations led nowhere. He started YouHeardThatNew while working at the desk of the DoubleTree Hotel in Somerset, N.J.

“For the next four or five years we were getting everything," LowKey says about the formation of the NMC. "Labels hated us, radio jocks hated us, the DJs hated us because we were getting shit we weren’t supposed to have.” Indeed, the NMC had become the bottleneck through which most major releases in the industry passed.

“The best thing about the New Music Cartel at that time was that they were one of 15 or 20 people who knew [new music] was coming,” says Joe La Puma, Complex's director of content strategy. “The label, the artist, their manager, and the New Music Cartel were the only people.”

Soon, LowKey’s success with YouHeardThatNew led to a gig writing for BET’s Sound Off blog, which gave him another level of access. It also led to one of the most infamous leaks in the NMC’s history. In May 2009, as a member of BET’s website staff, Low attended a Def Jam open house, where the label showcased the videos and records it was rolling out for the remainder of the year. Using a flipcam, LowKey recorded bootleg copies of all the videos, including The-Dream’s “Walking on the Moon,” featuring Kanye West, Fabolous’ “My Time,” featuring Jeremih, and “Paranoid,” from ’Ye’s 808s and Heartbreak. “Rihanna was in it, and that was the first time we saw her after the Chris Brown incident,” he says.

That night, LowKey posted them on both BET’s Sound Off blog and YouHeardThatNew, then forwarded them to the rest of the NMC. “The next morning the Internet’s going crazy about these new videos,” he says. “No one knows anything about the videos or when the albums are coming out. And Def Jam is screaming bloody murder at me. I was banned from Def Jam events for a good five months. The head of Def Jam called [BET head of programming] Stephen Hill and was like, ‘We want him fired. If he’s not fired we’re not dealing with you guys any more.’

But then everybody calmed down—it was actually helping them because it built so much buzz around those projects. Everybody covered it, from YBF to fucking Rolling Stone.”

“Today, we’re in rollout plans, we’re in marketing plans, we’re in strategy plans,” says LowKey. “They have to come to us, they have to strategize around us. And it’s not to sound cocky and not to toot our own horn. But for the guys that are blogging now and the guys that have their sites, we kinda laid our shit down and got stoned for the kids now. We made it possible for it to be cool to leak music.”

"The gift and the curse was when we got on the radar of top tier artists. That was the beginning of the end.” —hof

All members of the NMC perceived the network as serving many different functions, even if LowKey prioritized exclusives or Miss Info emphasizes the group’s role as a network of friends and peers. But its longest lasting impact may have been not on hip-hop’s ancillary industries (DJing, blogging)—technology shifted quickly, and soon social media eclipsed the new generation of gatekeepers—but on the music itself. At a time when the music industry was contracting and magazines were going bankrupt, NMC sites—especially 2DopeBoyz, OnSmash, and NahRight—played a major role in minting a new generation of hip-hop stars, many of whom remain industry staples today. (Eskay once referred to the 2009 XXL Freshman cover as the “NahRight All-Stars.”) Exclusives and free music drew an audience, but it was the blog’s role as a platform for rising artists, pre-SoundCloud, before the modern era of social media, that may be its lasting impact.

There’s no question NMC played a role in the success of some of the biggest artists of that era. Eskay claims he helped launch Wiz Khalifa, Wale, and Drake. Drake's success in particular he credits to NahRight blogger Nation, who started off as a commenter on the site. “He’s from Canada, and he was aware of Drake early,” says Eskay. “He put me on. He was like, ‘Listen to this kid, get used to him, he’s going to be big.’” (“Fuck what the blogs say, but shout out to Nation!” Drake once rapped.) Meka of 2DopeBoyz, meanwhile, suggests he and Shake were among the first to recognize the potential of Kendrick Lamar—then known as K-Dot—and Casey Veggies.

Of course, they were bloggers and not A&Rs, and for every success story there were a few more who didn’t stick; heavily promoted stars like Asher Roth ended up feeling like test cases for the frat rappers that followed. And there were blind spots in the NMC’s vision of what hip-hop was. An early Eskay post that has aged poorly declares “Snap Is Crap,” a reflection of the strong antipathy many New York bloggers felt for Atlanta’s dance trends. This was further reflected in the lack of coverage of artists like Soulja Boy, who exploded through Myspace and YouTube, Gucci Mane, many of whose fans were drawn to defunct streaming platform iMeem, and the listeners of various regional movements like jerk music and hyphy (again, artists who’d built fan bases through Myspace). By the time NMC was cresting in 2009-2010, blogs like Dirty Glove Bastard and Muzik Fene had begun serving fans outside the more New York-oriented audience of the NMC.

Perhaps the most infamous public conflagration over the blogs’ tastemaker status came with the rise of Odd Future in 2011. “Yo, fuck 2DopeBoyz and fuck NahRight,” Tyler, the Creator said on the opening track of his 2009 debut, Bastard. Frustrated by the lack of interest the sites had taken when he’d sent them his music, he also suggested on Bastard’s “Seven” that “Maybe I should buy some Hundreds, wear some fucking skinny jeans/And follow in your footsteps like a motherfucking millipede.” Shake from 2DopeBoyz returned fire in a post of the “DTA Raps” video from onetime Odd Future member Casey Veggies, referring to Tyler as “some clown that got all butt hurt” and a “loser,” while the former OF member raps over Tyler's beat. Neither Shake nor Meka posted the group’s music from that time on.

Meka says 2DopeBoyz never received any emails or tweets from Tyler in the first place, and that the first they heard of the group was when Tyler was dissing them on Bastard. He believes it was merely a marketing ploy, but one that boosted traffic to his site. “If anything,” Meka says, “they made it a lot easier for me to make sure my mom never has to pay another bill.” Whether or not the scheme was pure marketing, Odd Future’s irreverence toward these new gatekeepers ended up propelling OF further as an underdog narrative took hold. It was also a sign that the NMC had transformed fully from industry upstarts to a part of the establishment.

Perhaps the biggest signal of the bloggers’ clout was Eskay’s response to the controversy that erupted in 2009 when Asher Roth quoted Don Imus’ racist “nappy headed hoes” statement on Twitter. The week that Roth’s debut album was released, Eskay ceased posting any Asher Roth content, even after being contacted by Roth’s manager, Scooter Braun. Although Eskay seemed won over by Braun's explanation that Roth had been mocking Imus, he held the line, temporarily stopped posting Roth's music, and insisted Roth should respond publicly to the controversy. Roth issued a formal apology two days later, and Eskay declared the ban "lifted."

“We made it possible for it to be cool to leak music,”

—LowKey

The NMC found the grey area in which it operated became a lot more black and white after the Feds moved in on DaJaz1 and OnSmash over Thanksgiving 2010. What the DJ Drama raid of 2007 had been for hip-hop mixtape culture, the 2010 website shutdown was for hip-hop blogs. The government alleged that OnSmash was accused of “copyright infringement and selling counterfeit goods.” “It blindsided us,” LowKey says of the NMC's reaction to the shutdown of his peers' sites. “We knew we were pissing people off, but to this point?”

For Hof—who at the end of last year received his onsmash.com domain name back from the government—the seizure came as a surprise. “It was always my general assumption that things came from an artist or it had an artist, manager, or label’s blessing,” he says. “Sometimes artist management gives us a record to put out because the label doesn’t want it out. I can’t tell you how many times I had labels freaking out on me because a manager gave us a video that the label couldn’t put out because of clearances—whether it be a sample clearance or a location they shot it at didn’t get cleared, or people featured in the video. At the time, there was a certain naivete that I had to all that. The gift and the curse was when we got on the radar of top tier artists. That was the beginning of the end.”

Hof suspects it wasn’t merely about music piracy but about competing interests for the next generation of music distribution. “Don't forget, Vevo was coming up at the time,” he says. “UMG and Sony and all them were creating Vevo. There was an unwillingness—all of a sudden they felt like they didn’t need us any more. They were about to start their own thing. I had a lot of conversations with people at Universal, at Sony, at Warner, to legitimize what we were all doing. And that ultimately might have put us on a radar that we might not have been on [previously].”

The crackdown ushered in the inevitable end of the rap blog era, but there is perhaps an upside to that. “[The raid] forced a lot of the sites and media companies in general to evolve what the online content was, so it was more proprietary, something that wasn’t just reposting other music,” says BFred. “Long term, it had positive effects. It allowed a site like Complex and other sites to come in and do more cultural analysis, more reporting, which ultimately is a good thing for the culture. It creates more of a dialogue in the culture, rather than ‘Here’s new songs, let’s yell at each other in the comments section.’”

Other developments took their toll on the model as well: The arrival of social media meant music fans no longer relied on gatekeepers to suggest artists, instead relying on word of mouth, the suggestions of peers, and virality. Big players stepped into the game as well; DJs who’d once mocked the blogs ended up establishing sites of their own, leveraging their relationships in competition with the members of the NMC, as did hip-hop journalist Elliott Wilson, who’d founded Rap Radar in 2009 and soon ate away at NahRight’s hold on the center of the hip-hop discussion. And now, streaming music has become the platform that offers curated music to a vast audience looking for a filter.

As a result, many of the members of NMC began to diversify. Miss Info had always been a journalist, and Hof never left the music industry. But Meka began DJing on the side and ended up working as a tour DJ for Kendrick, Ab-Soul, and even Iggy Azalea. LowKey began working in the industry for Kevin Liles and consulting on marketing for Trae tha Truth. His upfront personality eventually led him to jobs hosting the Hennypalooza day parties and a show on Beats 1, a full-circle move for a man who’d started out his post-collegiate career unsuccessfully mailing out air checks. Mr. X has a show on Dash radio.

For Eskay, meanwhile, NahRight remains his focus, and he continues to update it daily. “Eskay was resistant to changing what NahRight was,” BFred says. “Complex offered its services to redesign NahRight for him several times, and he turned it down because I think he wanted to stay true to what NahRight was, not make it into some whole fancy bigger thing. Ultimately the thing that made NahRight—its simplicity and focus—is the thing that ended up making it less of a central part of the conversation, once the online culture evolved into this more complicated, nuanced thing. He stayed doing his thing, it's still valuable. But in some ways the culture has moved into a different place.”