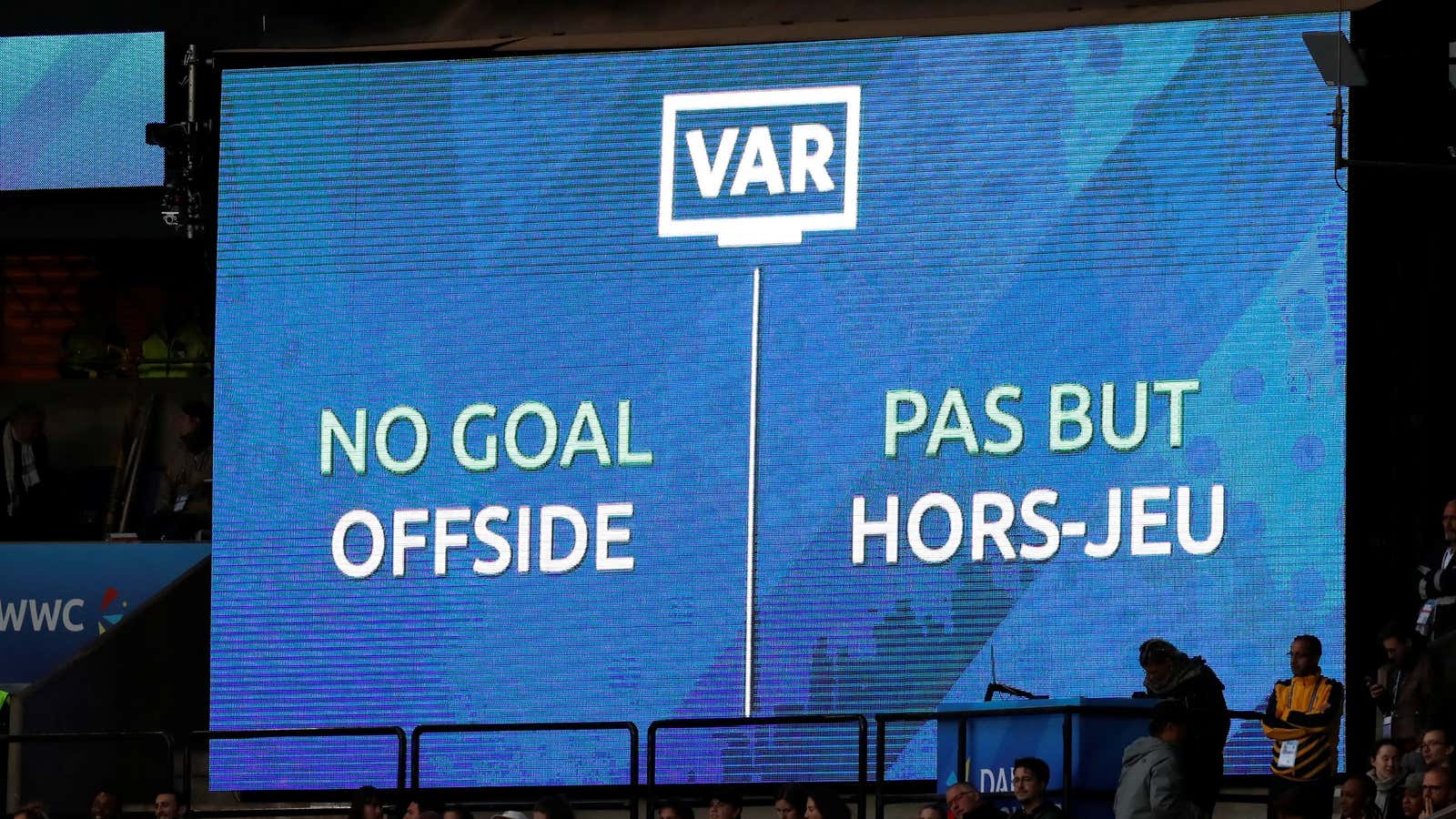

Oh no! The video assisted referee, or VAR for short, has done it again. VAR, which allows soccer’s officials to watch video replays to review key moments of matches, has only been part of the game for a short while, but it is again at the center of controversy.

Its latest piece of troublemaking came in the final of the CAF African Champions League, where Esperance of Tunisia faced Wydad Casablanca. With Esperance a goal ahead in the second leg, Wydad thought that they had scored an equalizer, only for it to be disallowed. The team asked the video assistant referee to review the decision, only to be told that the pitchside equipment was not working, and so they left the field in protest. After a significant delay, the referee awarded the match, and therefore the trophy, to Esperance.

Subsequently, CAF (Confederation of African Football), the continent’s top soccer body has ordered Esperance to return their medals, and for the second leg to be replayed. Once again, it seems to many VAR is more trouble than it is worth.

The argument goes that if there were no such technology, no final right of appeal, then both teams would merely have to abide by the result. The match officials, so this argument continues, are highly trained; if, after all that training, they still fail to spot an infringement, then tough luck. That’s just life.

It’s a popular outlook, shared by those who believe the arrival of VAR has robbed the game of its flow, that so much momentum and excitement is lost when the match stops while the video replay is consulted. There is also a concern, voiced by leading figures within soccer, that the application of VAR is too often inconsistent; that instead of eradicating human error, VAR has exacerbated it.

The people proposing this argument have one major problem; technology has now been democratized. A few years ago, the video replay was only in the possession of the gods; that is to say, the television cameras. Now, thanks to the arrival of smartphones, there are potentially thousands of people within the stadium itself who can capture a decent camera angle of the game’s major incidents. There is a strong expectation that if all those people are able to review in real time exactly what has happened, then match officials should be too. It seems farcical that, in contests of such importance, officials should maintain a wilful ignorance about what exactly might have happened, even as everyone else in the ground can readily access footage of these incidents via social media.

Yet people who dislike VAR are not merely afraid of the march of the future; even though, oddly enough, two of the biggest English Premier League clubs will not show VAR replays in their stadiums next year. There is a particular fear that games of soccer risk becoming on-field lawsuits, where crucial moments are endlessly re-litigated, with players forever asking for the cameras to be consulted.

The fear here is that soccer will be beset by stoppages every few minutes; that it will go the way of sports like American football and basketball whose structure often seems preoccupied with the accommodation of TV commercial breaks.

These fears are largely misplaced. VAR has had some problems with its application, but these can be regarded for the most part as teething problems. It will take time for match officials to get it right, but the trick—as seems to be visible from the NBA’s experience—is to introduce changes gradually, not all at once; to carefully consider which incidents should be reviewed, and which should not. It is a work in progress, and will naturally involve a period of adjustment. But it is arguably better to have VAR in place than to have a situation where a country is denied a place at a World Cup partly due to a clear handball during a playoff game.

The question ultimately comes down to a philosophical one, and one which is at the very heart of football. One reason for the game’s enduring popularity is perhaps that, contrary to other sports, the best team does not always win. Soccer is such a low-scoring sport by comparison with others that the margins for success and failure are particularly small; this means that acts of gamesmanship—a sly foul here, a cunning dive there—can be especially pivotal.

The World Cup, for example, has long thrived on a culture of injustice, with Diego Maradona’s handball against England and Geoff Hurst’s goal against Germany providing two of the tournament’s defining events. That inherent unfairness, where football so closely mirrors life—where there are no action replays, where the bad people win, where the good ones frequently do not get what they deserve—is, for many viewers, soccer’s essential attraction.

Yet there is much more to soccer than its injustice. There is its beauty, its capacity to thrill with attacking play of rare delight and defensive play of awe-inspiring resilience; and, crucially, none of that is threatened in the long run by the introduction of greater fairness. So may the best team win; because it is high time that they always did.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox