The new Neon series about the fight to have gender equality enshrined in the US Constitution is a fun 70s romp with a bitter twist, writes Catherine McGregor.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, they say, and right now that’s especially true for television, which is filled to the gills with historical series attempting to say profound things about America’s current political moment. I’m still workshopping a name, but for now let’s call it ‘‘How we got into this mess” TV. It includes shows like The Loudest Voice in the Room, on the rise of Fox News; Central Park Five dramatisation When They See Us, which features Donald Trump’s late-’80s awakening as a rabble-rouser and race-baiter; and Chernobyl, a queasy exploration of how political myths and alternate realities can lead to horrific real-world consequences.

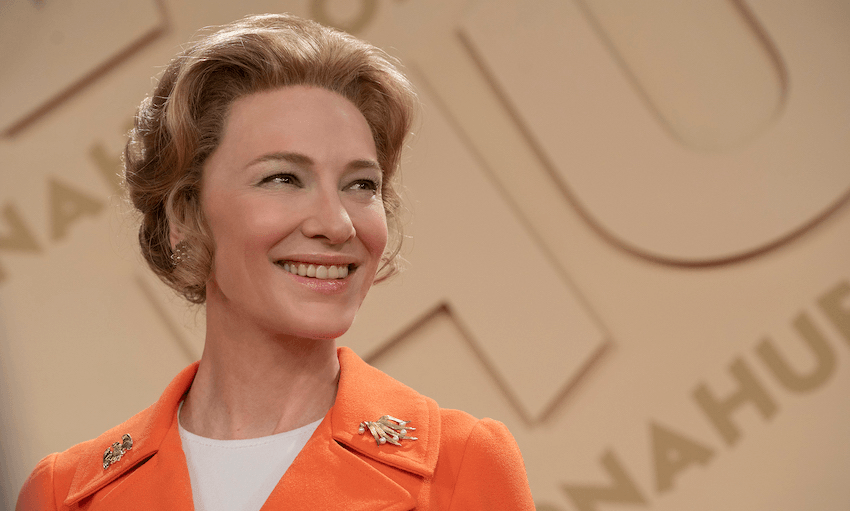

The latest addition to the genre is Mrs. America, a nine part series telling the story of the movement to have the Equal Rights Amendment, guaranteeing women equal protection under law, added to the United States Constitution. It also tells the story of the movement to stop it, spearheaded by conservative firebrand Phyllis Schlafly, played here with monstrous charm by Cate Blanchett. Probably the only comparable example of a cinema legend appearing in a TV show like this is Meryl Streep’s turn in Big Little Lies, although Blanchett’s role is far larger and more complex.

There are similarities to Streep and Blanchett’s television forays, however, and not only because they both played dangerously smart conservative women. Like Streep, with her false teeth and theatrical facial expressions, Blanchett’s performance often teeters on the edge of camp. The housewife whose primped and polished exterior hides a malevolent soul is a cinematic mainstay, and Blanchett is clearly having fun embodying all of Schlafly’s grotesque contradictions. With her shellac-ed bouffant and pussy bow dresses, she’s a 50s archetype transposed into the early 1970s where repressed Eisenhower optimism has given way to sexual liberation and Vietnam-inspired dread.

It’s her perfectly put together appearance – and her ever-present, tightly condescending smile – that helps give the words that come out of her mouth such impact. Decades before Fox News was even a twinkle in Roger Ailes’ lecherous eye, Schlafly understood the unique power of a beautiful woman making politically inflammatory claims on TV. And if those claims have little basis in fact, well so what? After Schlafly tells talk show host Phil Donahue that ERA supporters “want to legislate away any differences between the sexes which will mean goodbye girl scouts and hello unisex bathrooms” he asks if she’s fact-checked her assertions. She sidesteps, sweetly replying that ratifying the ERA would be the first step on a slippery slope to a “feminist totalitarian nightmare” before turning on her heels and stalking off. Schlafly was an early proponent of what Stephen Colbert would later term “truthiness” – her claims seemed plausible enough that they could be true, and that was enough to make them so for the millions of women who soon joined her cause.

According to historians and people who knew her, this malignly calculating version of Schlafly was true to life, but Mrs. America also spends a good chunk of its early episodes working viewers’ empathy valves on Schlafly’s behalf. In a clear attempt to draw parallels with the “women’s libbers” she loathes, Schlafly is shown being routinely belittled, under-estimated and sexually harassed. As the only woman in a Capitol Hill meeting on nuclear arms control, her area of expertise, she’s talked over and asked to take notes – and it’s there and then that she decides to pivot to anti-ERA activism, realising that defending the rights of “homemakers” will get her more attention than critiquing defence policy ever could.

Over on the other side of the ERA divide, the women arguing for equal rights are facing their own battles, personal and political. While Schlafly, as star and chief “anti-feminist”, is a whirlwind force throughout Mrs. America, there’s a secondary focus on the women lined up to defeat her. And what women they are. It’s hard to decide what’s more of a thrill: watching Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shirley Chisholm formulate what would become the modern women’s movement, or the incredible cast Mrs. America has assembled to play them. The initial episodes zero in on those three feminist heroes, played respectively by Rose Byrne, Tracey Ullman and Uzo Aduba, but the cast is stacked with talent to an almost distracting degree. Margo Martindale, Melanie Lynskey, Elizabeth Banks, Jeanne Tripplehorn, John Slattery, Sarah Paulson – everywhere you turn, there’s another award-winning face. This is undoubtedly television of quality, but while the show has Emmy-bait all over it, perhaps the best thing about Mrs. America is that it’s also so much fun.

A lot of the joy with which the show is infused is down to showrunner Dahvi Waller, whose previous experience on Mad Men and Halt and Catch Fire no doubt taught her how to create period pieces that don’t feel staid. Her Mrs. America is both colourful and stylish – Schlafly, for all her faults, apparently had impeccable fashion sense – with a soundtrack that captures the energy of the era, if not always with 100% accuracy to the time. Using Walter Murphy’s disco-funk version of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony over the opening credits is inspired, even though it wasn’t released until 1976, five years after the Mrs. America story begins.

For a majority of viewers in the US, the central question of the series – will the Equal Rights Amendment be ratified by all 50 states, and thus become law? – is likely moot. They know how it turned out, for better or worse. We here in New Zealand have the benefit of ignorance, so I won’t spoil it for you. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, wrote William Blake, but foresight is better. He was probably right, though sometimes it’s best not to know what’s coming down the tracks for us. If we did, would we ever sleep again?