Created in 1997, Lilith Fair was intended as a testament to female creativity and empowerment – a Lollapalooza-style touring caravan that would consist solely of female solo artists and bands led by women. That said, the festival, co-founded by Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan, promoted a narrow form of feminism in its initial incarnation: Tracy Chapman and India.Arie were among the few black artists on a roster that skewed towards the “sensitive” end of the musical spectrum, as the Observer put it at the time.

The festival’s second incarnation, however, branched out into edgier territory with the likes of Erykah Badu, Liz Phair and a breaking rapper hailing from Portsmouth, Virginia, named Missy Elliott. She already had a platinum-certified 1997 debut album, Supa Dupa Fly, and an iconic image immortalised in video collaborations with Hype Williams. But her sets at Lilith Fair, beginning in Palm Beach, Florida, on 26 July 1998, would be her first live performances; ones that demonstrated the potency of this legend in the making and expanded industry perceptions of what gigs could even be.

Only 25 at the time, Elliott was making a name for herself in the intensely masculine world of hip-hop. The genre was in flux, partly in the wake of the deaths of 2Pac and the Notorious BIG, and inventive artists such as Melissa Arnette Elliott could thrive: with a debut album recorded in just two weeks, her withering flow was partnered with a futurist sound: Timbaland instrumentals that Ed Simons of the Chemical Brothers said at the time had “an English experimental feel” to them. Supa Dupa Fly felt more in line with the optimism of the new millennium than the strife of the 90s; Missy said: “Rap’s coming around again to stuff that isn’t all about discussing negative things. That’s why I think my music may be getting over.”

Edward Helmore of Mojo magazine claimed in April 1998 that “an invitation to join Lilith was an opportunity to demonstrate industry clout and a public display of unity”. This much is evident throughout Elliott’s set, the first time she used the nickname “Misdemeanor”.

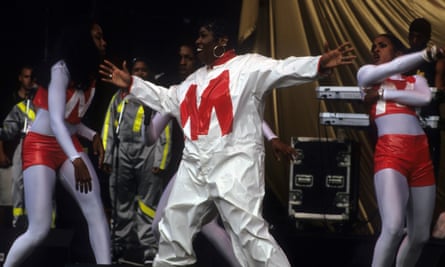

The first misdemeanours were her outfits, including one reused from the music video for hit single The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly): imagine a black Michelin woman. With mute “video vixens” the pervasive face of femininity in rap music videos at the time, Elliott’s inflatable black orb was a clear indication of an artist doing things on her own terms. Her frame didn’t match the typical vixen silhouette, and so she played on this in the most extreme way possible, pointing to the absurdity of those who might use her weight against her to undermine her talent. She represented middle America’s worst nightmare: a gigantic black woman in full command. More prosaically, it was also difficult to move about on stage in the outfit, demonstrating Elliott’s dedication to putting on a spectacle. “Why was I in that?” she replied to a fan wondering about the outfit on Twitter last year. “I don’t know – cuz I’m Missy.”

Elliott came on stage to Breathe by the Prodigy, signposting her unpredictability and irreverence; accompanied by a live band, her sets only lasted around 15 minutes, but left the crowd “stunned” according to Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield. This rule-breaking set her apart, along with her cartoonish playfulness. While there were several other male acts such as Busta Rhymes, Wu-Tang Clan and Outkast who were tapping into a more exuberant image during the “shiny suits” era of rap, Elliott pointed towards outright fantasy, where aesthetics could be transcendent. Many hip-hop artists, like Elliott, had a tough upbringing, amid poverty and a violent father, and her wild creativity perhaps comes from wanting to make art that hoists you out of your circumstances through sheer imagination.

Everything is carefully curated and had wider meaning for Elliott, right down to the Betty Boop finger waves in her hair and her ruler-length coloured acrylic nails. This was a look that was distinctly black, not watered down to suit the once melanin-deficient Lilith Fair. Helmore compared Elliott’s bravado to that of Chaka Khan, suggesting that she “breathed new life into a genre that has been in danger of setting rigid as karaoke with beats” and that she was “destined to become hip-hop’s first female media mogul”, an accolade that she achieved, and then some.

A review of the set from Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo commented that Elliott “spent more time changing clothes during the performance or running through the audience than singing”, clearly a criticism, but actually pointing to one of the most pioneering aspects of Elliott as an artist. This month saw the release of the music video for WAP by Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B. The concept was clearly an homage to the black camp aesthetic that Elliott perfected at the beginning of her career: seeing the two artists stroll down the corridor of an ostentatious and surreal mansion is a clear callback to Elliott’s Beep Me 911 and their kinship is arguably reminiscent of that of Elliott and fellow female rap pioneer Lil’ Kim. Elliott was quoted as saying in i-D Magazine in 1998, “if I was to talk and rap what everyone else sung about, it wouldn’t make me special … Hopefully females that might have been scared to go out there and be a writer and producer will see that I’m successful and give it a try.” This mindset is her legacy, clearly apparent in rap today. The recent cadre of female rappers such as Flo Milli, CupcakKe and Megan Thee Stallion are clearly drawing on the misadventure and unashamed filth that made us fall in love with Elliott.

Though there is little archival documentation of Elliott’s Lilith Fair sets, they are indicative of something much bigger. Elliott, now in the fourth decade of her career, is both benchmark and blueprint for much of the female-led hip-hop and campy pop that is now ever-present. At Lilith Fair, she blew up, in every sense.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion