This report has been updated with a new version for 2022.

State of Phone Justice:

Local jails, state prisons and private phone providers

by

Peter Wagner and

Alexi Jones

February 2019

Press release

At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, people behind bars in the U.S. are often forced to pay astronomical rates to call their loved ones or lawyers. Why? Because phone companies bait prisons and jails into charging high phone rates in exchange for a share of the revenue.

The good news is that, in the last decade, we’ve made this industry considerably fairer:

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) capped the cost of out-of-state phone calls from both prisons and jails at about 21 cents a minute;

- The FCC capped many of the abusive fees that providers used to extract extra profits from consumers; and

- Most state prison systems lowered their rates even further and also lowered rates for in-state calls. 1

However, the vast majority of our progress has been in state-run prisons. In county- and city-run jails — where predatory contracts get little attention — instate phone calls can still cost $1 per minute, or more. Moreover, phone providers continue to extract additional profits by charging consumers hidden fees 2 and are taking aggressive steps to limit competition in the industry.

These high rates and fees can be disastrous for people incarcerated in local jails. Local jails are very different from state prisons: On a given day, 3 out of 4 people held in jails under local authority have not even been convicted, much less sentenced. The vast majority are being held pretrial, and many will remain behind bars unless they can make bail. Charging pretrial defendants high prices for phone calls punishes people who are legally innocent, drives up costs for their appointed counsel, and makes it harder for them to contact family members and others who might help them post bail or build their defense. It also puts them at risk of losing their jobs, housing, and custody of their children while they are in jail awaiting trial.

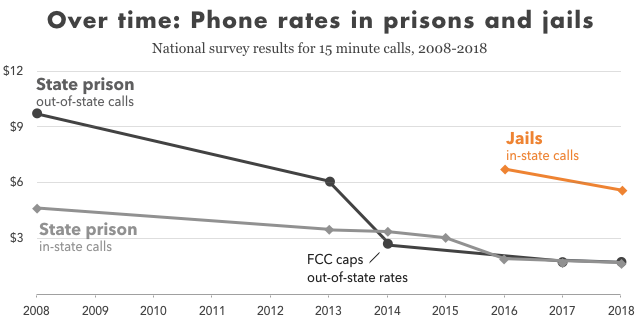

The cost of calls home from state prisons has declined as a result of the FCC’s caps and political pressure from the families, but jails still lag far behind. In fact, we estimate that approximately half of the small rate drop shown for jails is due to changes in data and methodology between the 2016 and 2018 surveys and may not reflect an actual drop in prices. (Shown are 6 national surveys of out-of-state calls from state prisons, 7 surveys of in-state calls from state prisons, and 2 surveys of in-state calls from jails. For more information about these surveys, see methodology). To see the states with the most significant rate drops, see Appendix Table 1.

The cost of calls home from state prisons has declined as a result of the FCC’s caps and political pressure from the families, but jails still lag far behind. In fact, we estimate that approximately half of the small rate drop shown for jails is due to changes in data and methodology between the 2016 and 2018 surveys and may not reflect an actual drop in prices. (Shown are 6 national surveys of out-of-state calls from state prisons, 7 surveys of in-state calls from state prisons, and 2 surveys of in-state calls from jails. For more information about these surveys, see methodology). To see the states with the most significant rate drops, see Appendix Table 1.

It is well within the power of both prisons and jails to negotiate for low phone rates for incarcerated people, by refusing to accept kickbacks (i.e. commissions) from the provider’s revenue and by striking harder bargains with the providers. And many state prisons have done so: Illinois prisons, notably, negotiated for phone calls costing less than a penny a minute.

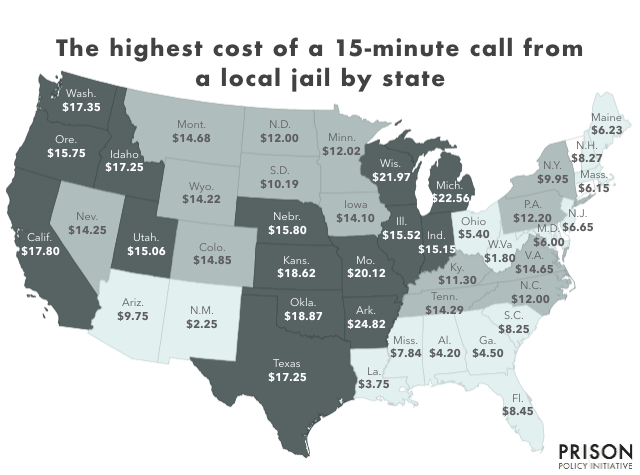

But in Illinois jails — which are run not by the state but by individual cities and counties — phone calls cost 52 times more, with a typical 15-minute call home from a jail in Illinois costing $7. In other states, the families of people in jail have to pay even more: A call from a Michigan jail costs about $12 on average, and can go as high as $22 for 15 minutes (compared to $2.40 from the state’s prison system).

Compare another facility: or

On average, phone calls from jail cost over three times more than phone calls from state prisons. Nationally, the average cost of a 15-minute call from jail is $5.74. This table and the map below show just how much more local jails are charging in each state than state prisons for the same 15 minute in-state phone call:

| State | Highest cost of a 15 minute in-state call from a jail (2018) | Average cost of a 15 minute in-state call from a jail (2018) | Cost of a 15 minute in-state call from a state prison (2018) | How many times higher the average jail rate is compared to the state prison's rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | $24.82 | $14.49 | $4.80 | 3.0 |

| California | $17.80 | $5.70 | $2.03 | 2.8 |

| Illinois | $15.52 | $7.11 | $0.14 | 52.7 |

| ⇡ Show all states ⇣ | ||||

| Michigan | $22.56 | $12.03 | $2.40 | 5.0 |

| New York | $9.95 | $7.79 | $0.65 | 12.0 |

| Texas | $17.25 | $6.53 | $0.90 | 7.3 |

What accounts for these vast price disparities? Local jails are not significantly more expensive to serve than state prisons. Rather, phone providers have learned how to take advantage of the inherent weaknesses in how local jails, as opposed to state prisons, approach contracting. The result is that jails sign contracts with high rates that are particularly profitable for the providers.

State prisons have, compared to jails, several advantages:

- State prisons, which are larger than jails, have the means to analyze the costs and benefits of proposed contracts (and often write their own contracts). Their analyses can reveal hidden fiscal and policy costs underlying too-good-to-be-true vendor proposals.

- State prisons tend to be run by appointees of the Governor, so they are often insulated from short-term financial and political pressures, and are often supported by career staff who have years of experience negotiating with billion-dollar communications companies.

- The typical prison sentence is about 29 months 8 so the families of people in prison can put sustained political pressure on the prison system to negotiate fairer prices. 9

- Many state legislatures have passed laws lowering the cost of calls home from state prisons. 10

Jails, meanwhile, are vulnerable to signing bad contracts because:

- County jails tend to be smaller, 11 and unless they rely on expensive consultants, their staff will have a harder time negotiating sophisticated telecommunications contracts, and may even rely on language suggested by the providers.

- Local governments (which run jails) tend to have smaller or less flexible budgets and are less eager to think long-term than state governments (which run prisons). And in particular, when jails are run by elected officials, they may not be looking beyond the next election.

- The typical person booked into a jail is released in hours or days and may make only a few calls, so it is difficult for their families to put sustained political pressure on jail administrators to negotiate better contracts.

- Many state legislatures — and by extension the Public Utility Commissions and other regulatory and civil society organizations — pay very little attention to individual jails or the state’s aggregated jail policy.

So to recap, the companies are savvy and very effective at cutting self-serving contracts with the jails. But in addition to their high rates in jails, companies also slip in hidden fees that exploit families and, as we will see, shortchange facilities.

How charging families hidden fees shortchanges both families and facilities

Phone providers are counting on facilities, regulators, legislators, journalists and the readers of this report to focus only on per-minute phone rates, ignoring their other major source of revenue: fees.

Because the typical reader unfamiliar with telecommunications regulations would assume that rates and fees are the same thing, it is helpful to step back and clarify our definitions:

- Rates:

- This is what you pay per minute, including any higher charge for the first minute of the call.

- Fees:

- This is everything else you might pay for “services” related to the call, such as fees to open an account, have an account, fund an account, close an account, get a refund, receive a paper bill, etc.

Charging high consumer fees allows phone providers to technically abide by rate caps while generating a new source of revenue — one on which, as a bonus, they do not have to pay commissions to facilities. As long as these fees are ignored or dismissed as an “ancillary” issue, companies will continue to use them as — in the FCC’s words — “the chief source of consumer abuse.” Historically, these fees are not trivial, but “can increase the cost of families staying in touch … by as much as 40%.”

To its credit, the FCC made tremendous progress on this issue in 2015, capping some fees and eliminating others. 12 Just one of the reforms — capping the fee charged for a credit card purchase (to a still significant $3.00) 13 — has saved consumers $48 million every year since. 14

Sadly, the most unscrupulous providers have found ways to evade these new regulations, and continue to charge unconscionable fees.

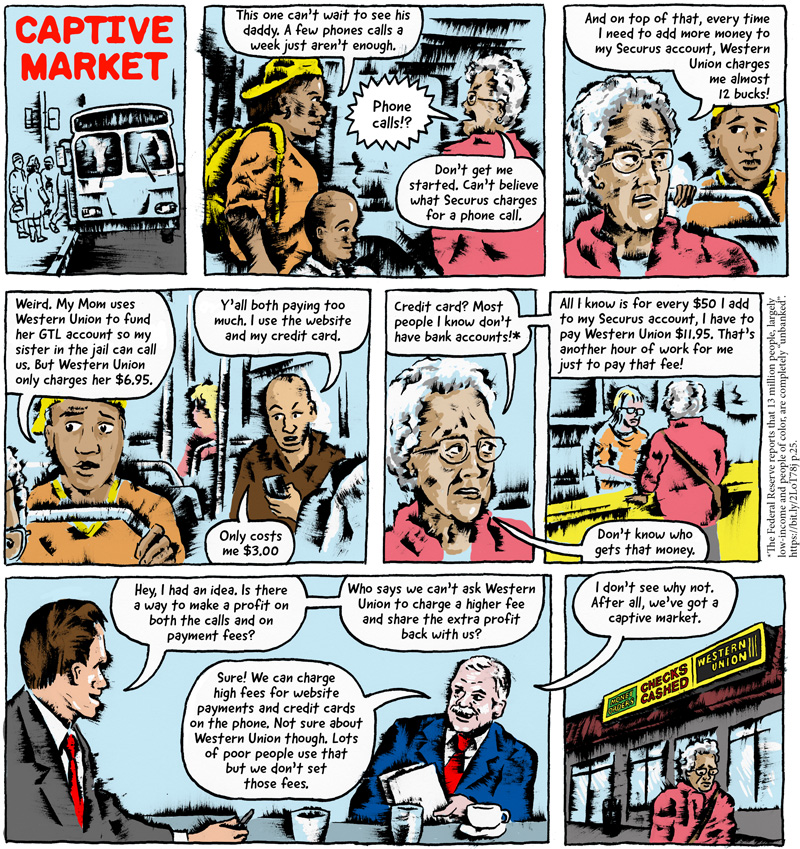

For example, many people living in poverty (who are among the most likely to be incarcerated or have incarcerated loved ones) do not have bank accounts and often pay their bills by money transfer via WesternUnion or Moneygram. 15 WesternUnion and MoneyGram charge a standard price of about $6.00 16 to send a payment to most companies, including GTL, 17 NCIC, Telmate, Paytel, or ICSolutions. (See table.)

| Provider | Moneygram Fee | WesternUnion Fee |

|---|---|---|

| Amtel | N/A | $9.99 |

| GTL | N/A | $6.95 |

| Infinity | $6.95 | N/A |

| Lattice Inc | N/A | $9.95 |

| NCIC | $4.99 | $6.50 |

| Paytel | $6.49 | $5.00 |

| Securus | $11.99 | $11.95 |

| Telmate | $6.99 | N/A |

| ICSolutions | N/A | $5.00 |

However, other companies have arranged 18 hidden profits in these third party payment systems. For the same $25 payment to Amtel, Lattice or Securus, Western Union and MoneyGram charge a shocking $10-12. The explanation is that Western Union and MoneyGram are collecting a portion of this fee on behalf of the phone providers, something that the FCC intended to prohibit. Amtel has even admitted to the FCC that it receives a portion of Western Union’s fees. Western Union calls these payments a “revenue share” in its correspondence and a “referral fee” in its contracts. Families and facilities would be right to call this hidden fee a form of exploitation.

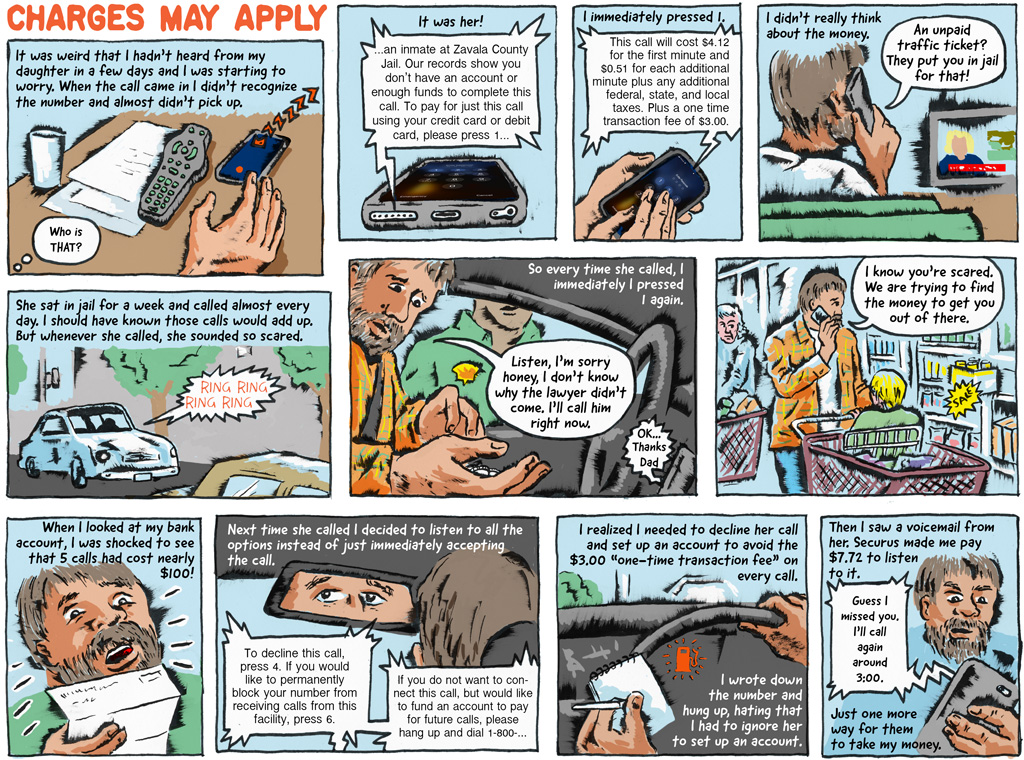

For example, Securus goes out of its way to make it hard for family members to create and fund accounts in an efficient manner. Rather than encourage families to create pre-paid accounts — or to add funds to a depleted account — Securus instead steers people to pay for each call individually. By emotionally manipulating family members into paying for single calls rather than creating accounts (see comic below), the companies drive up fee revenue. 19 Other services — such as charging families to listen to voicemails from their loved ones in jail — similarly manipulate consumers and increase revenue from fees. Neither public safety nor consumer “convenience” benefit from these unnecessary but highly profitable call products.

It’s easy to see how the phone providers benefit from imposing a variety of burdensome fees, but how this practice also hurts facilities does not get enough attention. Facilities’ commissions come from phone calls themselves, not the fees attached to them. Facilities should therefore want families to be making more phone calls, but when families are bled dry by high fees, the number of calls they can afford to make goes down. That outcome is fine with the providers, but leaves the facilities with less revenue than they expect. (For sheriffs who already feel uncomfortable charging families $1/minute, understanding that they, too, are being ripped off by providers should push them to negotiate for contracts that prioritize the interests of local families over large corporations.)

The providers are consolidating the market to limit facilities’ choices and lock them into unfair contracts

Phone providers, as we explain above, are skilled at writing self-serving contracts that burden consumers with unfair rates and fees. It is therefore in the interest of correctional facilities to be careful and conscientious in selecting a phone contract. But the odds of negotiating a fair contract — odds already tilted against facilities, as we’ve shown — are declining as phone companies buy up their direct competitors and the providers of related correctional services.

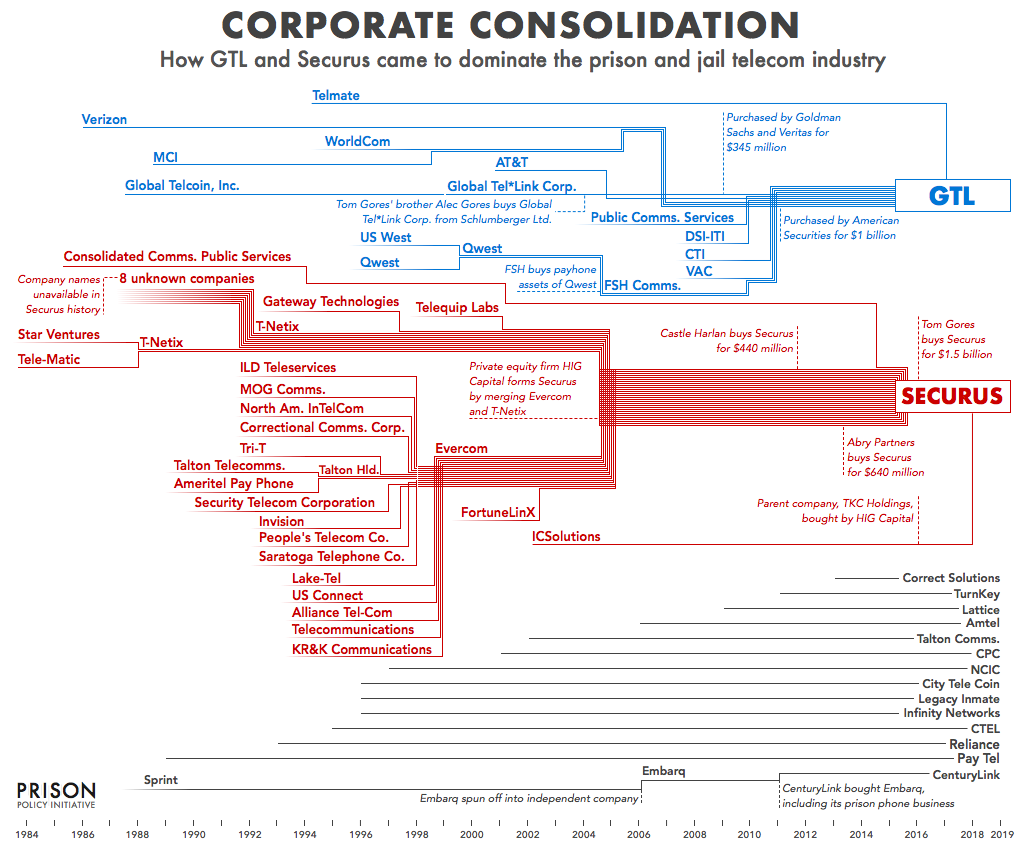

First, as the below timeline illustrates, providers are limiting facilities’ choice of vendor by directly purchasing their competitors:

This timeline of mergers in the prison/jail telephone space shows how GTL and Securus have, over time, gobbled up many of their competitors. Not shown are the respective sizes

20 of each of the companies (GTL is the largest, followed by Securus and — if it were an independent company — ICSolutions), or the fact that some companies like CenturyLink operate only in partnership with Securus and ICSolutions or that for some companies (like AT&T or Verizon) only the portion of their business that was prison and jail phones was transferred. Additionally, it is possible that one corporate merger on this timeline may be undone, as Securus’ purchase of ICSolutions is currently under review by the Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice.

21

This timeline of mergers in the prison/jail telephone space shows how GTL and Securus have, over time, gobbled up many of their competitors. Not shown are the respective sizes

20 of each of the companies (GTL is the largest, followed by Securus and — if it were an independent company — ICSolutions), or the fact that some companies like CenturyLink operate only in partnership with Securus and ICSolutions or that for some companies (like AT&T or Verizon) only the portion of their business that was prison and jail phones was transferred. Additionally, it is possible that one corporate merger on this timeline may be undone, as Securus’ purchase of ICSolutions is currently under review by the Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice.

21

The fact that only two companies now control most of the correctional phone market — and are poised to control even more if Securus acquires ICSolutions — is bad news for both facilities and consumers.

But the dominant companies have a second monopoly strategy, which is both more subtle and more harmful: buying non-telephone companies, in order to offer facilities packages of unrelated services in one huge bundled contract.

Bundled contracts combine phone calls with other services, such as video calling technology, electronic tablets, and money transfer for commissary accounts. This allows providers to shift profits from one service to another, thereby hiding the real costs of each service from the facility. Bundling also “locks in” contracts for the provider: It makes it more difficult for the facility to change vendors in the future, because the facility must now change their phone, email, commissary, and banking systems all at the same time.

So even the savviest of facilities are undercutting their future power by signing risky bundled contracts.

Compare another facility: or

Recommendations:

Taming the correctional phone market will require focusing on the areas where injustice is concentrated: Jails (rather than only prisons), fees (rather than only rates), and bundled contracts (rather than phone-only contracts). The bulk of the work lies with specific officials: contracting authorities, state legislatures, public utilities commissions, the FCC and Congress. For those groups, we recommend the following strategies:

Prisons and jails (and their oversight bodies):

- Prohibit commission payments in all of their forms.

- Negotiate better contracts based on delivering the best price to the consumer. (This goes beyond negotiating for “low” rates; and requires refusing unnecessary “extras” in the contract and looking at the total cost to the consumer, including fees.)

- Consider making phone calls free. In July 2018, New York City went further than prohibiting a commission and pledged to make phone calls free. This saves the poorest families critical funds, is a cost-effective investment in lowering recidivism, makes the justice process fairer and, because it reduces all of the hassle associated with accounts and billing, may not cost very much.

- Refuse to consider contracts that bundle telephone service with other goods and services. Facilities should always know what they are getting and what they — and the families — are paying for.

- Regularly conduct realistic tests of how your provider charges and treats consumers. Such tests should include test phone calls to staff phone numbers not already in the provider’s system and should include test deposits made via the mechanisms most likely to be used by the families of incarcerated people, including WesternUnion and MoneyGram. If you discover your provider is charging consumers beyond the fees and rates disclosed in your contract, demand that the provider make refunds.

Providers:

- Amtel, Lattice and Securus should stop making a profit on WesternUnion and MoneyGram payment fees. The consumers that use these services are among the lowest-income people in the country and should not be a target for exploitation.

- All providers should explore and promote alternative and lower-cost ways for low-income consumers — their target demographic — to pay for services. In particular, their customers who do not have bank accounts or credit/debit cards often pay the providers via WesternUnion or MoneyGram, which offer a network of retail locations to take cash to pay bills, but services like PayNearMe 22 can provide the same functionality at a much lower cost.

- During the request for proposals process, be honest with the facilities that high-rate/high-commission contracts are not in the facility’s best interests. Explain that low-rate/low-commission contracts produce comparable revenue for the facilities while increasing family contact.

State Public Utility Commissions:

- Follow the lead of Alabama and craft comprehensive regulation of the prison and jail telephone industry operating in your state.

- If your state statutes do not grant you sufficient regulatory authority over the industry, immediately go to the legislature and request it so that consumers and facilities in your state will not remain defenseless.

State legislatures:

- Require these correctional communications contracts be negotiated on the basis of the lowest price to the consumer. (This goes beyond setting a cap or banning “commissions.”) Ensure that these rules apply to both prisons and jails.

- Alternatively, consider establishing a system that sets a maximum commission amount on a per minute basis — at for example 1 cents a minute — in order to give jails an economic incentive to both increase call volume and keep the total cost to consumer low now and in the future.

- Require the state prison system to negotiate its contract to give county jails the option to opt in to the state contract and its terms. 23 Depending on the number of counties in a state and the resources of each county; this could be a powerful way to reduce a burden on county jails while lowering the cost to families.

- Encourage the State Public Utility Commission to investigate and regulate the prison and jail telephone industry. Be on the lookout for arguments from providers that they are exempt from regulation because they claim to be providing Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP) or Internet Protocol-enabled (IP-enabled) services. (Some states deregulated these services when cable telephone markets became competitive, but such reregulation should not apply in a quintessential monopoly such as prison and jail phone service.) Depending on your state, you may want to encourage your Public Utility Commission to reject such arguments as contrary to legislative intent, or you may need to pass clarifying legislation.

FCC:

- Return to actively investigating the industry. When Chairman Pai was Commissioner Pai, he opposed the majority’s proposal for how to regulate the industry, but he agreed that the market was dysfunctional and in need of active regulation. 24 Now that he is Chairman of the FCC, he can plot a course to regulate the industry that his consistent with his view of the limits of the FCC’s power. 25

- Reject Securus’ application to merge with ICSolutions.

- Investigate Amtel, Lattice and Securus for arranging a kickback with WesternUnion and MoneyGram in violation of the FCC’s order prohibiting marking up those money transfer fees.

Congress:

- Pass legislation like the last Congress’ S. 2520 Inmate Calling Technical Corrections Act which would clarify the FCC’s authority to regulate both in-state and out-of-state calls, fees, and advanced technology like video calling.

Appendices and Exhibits:

Appendix Table 1

| State | Cost of a 15 minute in-state call (2008) | Cost of a 15 minute in-state call (2019) | Rate Drop (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | $5.19 | $3.15 | 39% |

| Alabama | $6.45 | $3.34 | 48% |

| Arkansas | $4.68 | $4.80 | -3% |

| Arizona | $5.40 | $3.34 | 38% |

| California | $4.23 | $2.03 | 52% |

| Colorado | $5.97 | $1.80 | 70% |

| Connecticut | $4.97 | $3.65 | 27% |

| Delaware | $5.30 | $0.60 | 89% |

| Florida | $1.76 | $2.10 | -19% |

| Georgia | $4.66 | $2.40 | 48% |

| Hawaii | $3.41 | $1.95 | 43% |

| Iowa | $5.36 | $1.65 | 69% |

| Idaho | $3.80 | $1.65 | 57% |

| Illinois | $6.14 | $0.14 | 98% |

| Indiana | $6.45 | $3.60 | 44% |

| Kansas | $7.70 | $2.70 | 65% |

| Kentucky | $4.30 | $3.15 | 27% |

| Louisiana | $4.81 | $3.15 | 35% |

| Massachusetts | $2.26 | $1.50 | 34% |

| Maryland | $7.05 | $0.52 | 93% |

| Maine | $5.05 | $1.35 | 73% |

| Michigan | $1.80 | $2.40 | -33% |

| Minnesota | $6.22 | $0.75 | 88% |

| Missouri | $2.40 | $0.75 | 69% |

| Mississippi | $4.70 | $0.59 | 87% |

| Montana | $5.55 | $2.15 | 61% |

| North Carolina | $4.91 | $1.50 | 69% |

| North Dakota | $5.82 | $1.19 | 80% |

| Nebraska | $1.40 | $0.94 | 33% |

| New Hampshire | $2.60 | $0.20 | 92% |

| New Jersey | $7.35 | $0.66 | 91% |

| New Mexico | $3.85 | $1.20 | 69% |

| Nevada | $2.50 | $1.65 | 34% |

| New York | $0.72 | $0.65 | 10% |

| Ohio | $5.55 | $0.75 | 86% |

| Oklahoma | $3.60 | $3.00 | 17% |

| Oregon | $13.61 | $2.40 | 82% |

| Pennsylvania | $5.99 | $0.89 | 85% |

| Rhode Island | $0.70 | $0.71 | -1% |

| South Carolina | $3.10 | $0.83 | 73% |

| South Dakota | $9.16 | $1.20 | 87% |

| Tennessee | $3.22 | $2.40 | 26% |

| Texas | $3.90 | $0.90 | 77% |

| Utah | $4.48 | $2.85 | 36% |

| Virginia | $5.75 | $0.61 | 89% |

| Vermont | $4.62 | $0.59 | 87% |

| Washington | $2.50 | $1.65 | 34% |

| Wisconsin | $5.17 | $1.80 | 65% |

| West Virginia | $3.65 | $0.48 | 87% |

| Wyoming | $3.55 | $1.65 | 54% |

- Appendix Table 2:

2018 Phone Rates Survey (2,055 local jails) - Appendix Table 3:

The most expensive jail phone calls in each state - Appendix Table 4:

Historical in-state and out-of-state prison phone rates, 2008-2019 - Appendix Table 5:

Commission totals for select counties in Michigan, 2014-2018 - Appendix Table 6:

Phone numbers for governor offices in each state, as of 2016 (for use as in-state phone numbers on provider websites.) - Appendix Table 7:

Phone rates and average daily population in Michigan jails - Appendix Table 8:

Phone industry timeline details [xlsx] - Appendix 9:

How rates compare between urban and rural counties, with national data and graphs for California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, and Ohio. - Appendix 10

Captive Market comic description - Appendix 11

Charges May Apply comic description

Exhibits

- Exhibit 1: Genesee County Michigan contract amendment after the FCC’s 2015 cap on fees went in to effect

- Exhibit 2: Email from Olga Rombach, Western Union National Account Executive to Karen Doss Harbison of AmTel, Re: FCC, September 3, 2014

- Exhibit 3: Amended Contract between Amtel (dba ATN) and Western Union, 2015 showing that in Alabama, Amtel will no longer be receiving a “referral fee” from Western Union.

Methodology

This report, its visuals and its appendices pull together several different surveys of rates:

- 2008 prisons: Prison Legal News collected the collect call rates in effect during 2007-2008. (At this time, most calls from prisons and jails were made collect.)

- 2013 prisons: Prison Legal News surveyed rates in 2012-2013. This survey is based on pre-paid rates, which was, by this time, the most common type of call from prisons and jails.

- 2014 prisons: We collected out-of-state rates and in-state rates by two different methodologies. Unfortunately, there is no singular survey of rates in 2014; but the PrisonPhoneJustice.org website (run by Prison Legal News) was keeping this website up to date with rate information on a rolling basis. This invaluable data collection is available historically through the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20140514050002/https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/ for May 14, 2014. Unfortunately, while PrisonPhoneJustice.org was collecting both collect and prepaid rates, only the in-state collect rates were available in this particular archive. To make the in-state collect rates comparable with the more common prepaid rates, we reduced the collect rates by 15%. (We note that in Prison Legal News’ 2012-2013 survey, prepaid rates were, with few outliers, typically 80-90% of collect rates, so we used the average difference of prepaid being 15% cheaper than collect. Additionally, we concluded that this assumption was reasonable because when the FCC set their rate caps in 2013, they set the prepaid cap of 21c at 15% lower than the collect rate of 25c a minute.)

For the out-of-state rates in 2014, we adjusted the 2013 survey data discussed above to make all states compliant with the new FCC out-of-state rate caps that went into effect in February 2014, limiting the cost of an out-of-state 15-minute call to $3.15. If states’ interstate caps were already below $3.15, we assumed their rates remained the same. Although we do not recall any instances of this, it is possible that some states may have taken the opportunity to immediately lower rates more than was required, and it is possible that our average of $2.80 is a slight overestimate. - 2015 prisons (in-state calls only): We used the same methodology and adjustments as described above for 2014, using the Internet Archive of PrisonPhoneJustice.org for January 26, 2015: http://web.archive.org/web/20150126120301/https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/ . (Out-of-state rate data is not available for 2015. Once the FCC’s out of state rate caps went into effect, much of the movement’s attention turned to in-state calls and out-of-state data does not appear to have been preserved.)

- 2016 prison and jail rates (in-state calls only): We used prison and jail intrastate prepaid rates data collected November 28 - December 12, 2016 by Lee Petro, former counsel for the Wright Petitioners, and the Prison Policy Initiative and made available in a submission to the FCC. Some counties had multiple facilities which were listed separately, but to make the dataset comparable, we merged those facilities together into one county entry for the purposes of our averages. We also removed police departments. This survey did not include many of the smaller companies such as NCIC, Correct Solutions, City TeleCoin, Lattice, AmTel, etc.; and did not include Telmate’s facilities because at the time, Telmate did not publish their rates online. (Like in the previous year, out-of-state data is not available for this year.)

- 2017 prisons: For 2017 in- and out-of-state rates, we used historical prepaid rate data available at prisonphonejustice.org. Each state page provides phone rates from previous years. For example, Maryland’s historical data can be found on this page: https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/state/MD/history/.

- 2018 prisons: We manually looked up prepaid rates 26 on providers’ websites for both intrastate and interstate calls in October of 2018. For intrastate calls, we got a rate quote for a phone call to each state’s governor’s office, consistent with the 2016 survey methodology, and for out-of-state calls we used an out-of-state number.

- 2018 jails (in-state calls only): With the exception of Reliance Telephone (see below), we manually looked up prepaid rates on providers’ websites November 1st 2018 to November 8th 2018 from an in-state number (generally the governor’s number) for each facility listed in the state. (This methodology may have understated the cost of in-state phone calls in a small number of counties if the facility was within the same “LATA” as the Governor’s office. In those cases, our rates may report a lower “local” call rate and not a typical in-state call; but we did not have a way to control for this directly except in Michigan where we manually chose a number located in another “LATA”). In April 2019, we updated the report with the rates of 163 counties that contract with Reliance Telephone.

As in 2016, counties that had multiple facilities were aggregated together, state prisons were kept separate from our data on jails, and we removed police departments. Some facilities are included twice because providers sometimes do not remove the rates/counties from contracts they have lost from their website. If we were unable to determine which provider currently contracts with a facility, we kept both.

The results of this survey are in Appendix Table 2, except for the NCIC facilities. (Unlike most providers, NCIC does not post their facility list or rates online. However, NCIC gave us their facility and price list so that we could calculate the average jail phone cost in each state on the condition that we not include their facility-level data in the Appendix.)

There are some slight differences in these surveys that are relevant to discuss. First, although more comprehensive than our 2016 data, this new survey is still missing data from several smaller prison phone companies that do not post their rates online, including Correct Solutions, City TeleCoin, Turnkey, Consolidated Telecom, Inc. (CTEL), etc. Second, some counties are in one survey but not the other, likely because they changed to or from a provider who does not post rates. Third, our newer survey includes two-lower cost providers that were not in the earlier survey. (Telmate’s decision to finally post their rates online and NCIC’s sharing of their rate data with us slightly reduces the average rates reported. Based on our analysis of counties for whom rates are available for both years, we believe that about half of the $1 decline in the cost of in-state 15 minute phone calls from 2016 to 2018 is the result of actual declines in the rates; and about half is the result of these two lower-cost providers making their data available.

For our survey of WesternUnion and Moneygram fees, we collected Western Union fee data for a $25 payment to different phone providers through in-person payments at Big E’s Supermarket, Easthampton, and Walgreens (225R King St., Northampton, MA) and through online chats with Western Union Representatives.

We collected data on MoneyGram’s fees for a $25 payment through Moneygram’s online BillPay feature and in person at Walmart (337 Russell St, Hadley, MA 01035).

Our interactive feature showing how much a phone call from various local jails would cost is based on our late 2018 survey of jail rates. The feature includes only some of the highest rates from jails in each state, so for the specific rates of all facilities, see appendix 2. The feature always shows the cost of the first minute of a call for the first minute of reading the webpage, and then apportions the cost of subsequent minutes to each subsequent second. For providers who bill only on the basis of individual minutes, our feature therefore underestimates the cost of each call.

Our timeline of consolidation in the industry is built upon reviewing every document we could find and a select number of interviews. The raw data and our notes on sourcing for transaction or change in status is in Appendix 8. Where ever possible, all dates in the visual are accurate to the nearest quarter year. Because it was not always clear when these privately held companies were founded or when they entered the prison or jail phone market, we choose to represent start dates that we were not sure about with a faded line. We used a break in the line to represent companies’ name changes. We did not include some very small companies, such as Michigan Paytel and American Phone Systems, some of which appeared to have substantial business relationships with large phone companies.

For the sidebar about unjustifiably high phone rates from jails, we used commission data for 2014-2017 for select counties in Michigan, which was collected via FOIA requests. With a goal of representing a range of counties, we requested records from at least 54 counties (out of 83 total) and received records from 44. This raw data is available in Appendix 5. To reduce the impact of artifacts in the data and to make it possible to compare counties of different sizes, we averaged the payments from multiple years and used the Average Daily Population reported in the Census of Jails, 2013 to calculate annual revenue per incarcerated person.

Footnotes

In-state call prices are important because in-state calls are about 92% of all calls. For state-by-state data on the drop in the cost of calling home from state prisons, see Appendix Table 1. ↩

These fees to open, have, fund and close accounts added up to almost 40% of what families spent on calls. And because these hidden fees typically do not pay commissions, shifting the families’ costs to fees was a way for the providers to pay facilities far less than they expect. For a summary of the FCC’s fee caps, see footnote 12; and for two of the industry’s current dirtiest tricks, see the How charging families hidden fees shortchanges both families and facilities section. For an alternative calculation on the value of fees, see the 2016 memorandum and contract between Securus and Genesee County, Michigan where the provider and the jail agreed to “move fees into rates” and increase the cost of calls by 23.41¢/minute so that the county and the provider could continue to make just as much money as before the FCC capped fees. ↩

These rates were stayed and ultimately overturned in Global Tel*Link v. Federal Communications Commission, 866 F.3d 397 (2017). ↩

Population analysis based on the 2013 Census of Jails. These are the rates adopted by the FCC, and under review by the Court in the GTL decision. The FCC modified these rates in August 2016, although they were never reviewed by the Court, to 13¢/19¢/21¢/31¢. While these 2016 rates gave more freedom to charge higher rates in smaller jails, they still do not come close to explaining the tremendous difference currently charged by jails as opposed to state prisons. ↩

Looking at kickbacks in terms of annual revenue per incarcerated person is more realistic than looking at percentages in the contract for at least three reasons: 1) Providers can soak up consumer funds via unnecessary fees without paying a commission, and 2) Some providers do not pay commissions for out-of-state calls and can easily reclassify in-state calls as out-of-state, and 3) Providers can steer calls to “premium” call types that pay smaller commissions. Therefore the best way to judge the revenue share in a contract is the actual financial outcome, not just individual terms in that contract. ↩

It’s worth mentioning that many high-commission, low-rate contracts are ICSolutions contracts, and that ICSolutions’ high-volume low-margin strategy appears to be a bid for marketshare as a way to make the company more valuable for acquisition. That is no doubt why Securus is currently seeking regulatory approval to purchase this competitor for $350 million. ↩

And to be sure, when calls are more expensive, people call less and that reduces revenue. To Securus — who also makes profits on ancillary fees and in other ways — this may not be important; but to facilities who seek to claim a portion of call revenue; higher rates can be particularly self-defeating. ↩

National Corrections Reporting Program: Time Served In State Prison, By Offense, Release Type, Sex, And Race, 2009 [zip] Table 8 ↩

See our 2017 summary. This pressure from state legislatures flows directly from the previous bullet point above that the families of people in state prisons are able to exercise effective political power, at least as compared to the families of people in jails. ↩

The median jail size is 46 people and the average size is 216 people (in average daily population), according to the 2006 Census of Jail Facilities. The largest jails tend to have the lowest rates. We found that the most urban counties have rates that average less than half that of the most rural jails. In most states, this pattern continues between the extremes: the more urban the county the more effective the jail is at getting lower rates. See our national figures and details for California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, and Ohio in Appendix 9. ↩

In summary, the FCC’s fee caps are:

- Payment by phone or website: $3 (previously up to $10)

- Payment via live operator: $5.95 (previously up to $10)

- Paper bills: $2 (previously up to $3.49)

- Markups and hidden profits on mandatory taxes, regulatory fees and third party transaction fees: $0 (Previously up to 25% of the cost of the call)

- All other ancillary fees: prohibited. (Previously, there were many of these charges, including $10 fees for refunds.) ↩

Most businesses quietly eat the cost of processing credit cards because they consider it the cost of doing business, but because these phone providers have monopoly contracts in each facility, they have zero fear of consumers switching providers to avoid unreasonable fees. ↩

We calculated the annual fee savings from reducing credit card deposit fees from as much as $9 per deposit to $3 per deposit by estimating the number of deposits made by the major providers and apportioning that to their share of the market.

For GTL: According to data GTL submitted to the FCC in 2014, GTL processed 11,408,021 credit card transaction fees. GTL reported charging between $2.00 and $9.00 per credit card transaction, and while we believe that most of those charges were at the high end; we made the conservative assumption that the typical GTL fee was the average of those two figures, or $5.50 per deposit. The FCC’s order thereby saves consumers $2.50 for each of the 11.4 million deposits made in a year at GTL facilities, for a savings of $28.5 million.

For Securus: Securus did not submit public-use information to the FCC that would allow a similar analysis. However, we know that at the time, Securus’ marketshare was about 1/3rd of GTL’s — Securus has an estimated 15.0% - 19.4% of the market (compared to GTL’s 46.0% - 52.9% - so we therefore estimated that Securus had 3,968,007 transactions in 2014. Securus’ credit card processing fee was $7.95, so reducing the fee to $3 would save $3.95 almost 4 million times a year for a savings of $19.6 million.

Since GTL and Securus control such a large slice of the market, we did not include estimates for other companies. Therefore, the actual money saved is higher than this estimate. ↩

According to the Federal Reserve, 13 million people in the United States do not have a checking, savings, or money market account. Another 46 million people are underbanked, meaning that they had a checking or savings account but also obtained financial products and services outside of the banking system. These populations are more likely to have low income, less education, or be in a racial or ethnic minority group. ↩

Alabama’s regulation of the prison and jail phone industry included an important provision around WesternUnion and MoneyGram payments that is both a model for other regulators and an insight into how these payments work. Alabama required that providers who accept WesternUnion and MoneyGram set the payment cost at no more than $5.95 or provide a copy of the contract demonstrating that the provider is not receiving any kind of revenue share from the payment company. What happened next is telling: Securus stopped accepting WesternUnion in Alabama and WesternUnion lowered the fees — in Alabama only — for the other providers. NCIC told us in an interview that they attempted to get the same $5.95 rate from Western Union nationwide, but that WesternUnion refused. ↩

GTL’s behavior in this regard has improved. As of our last survey on December 28, 2015, Western Union charged $11.95 to send a $25 payment to GTL (then called Global Tel*Link). As of our most recent survey in December 2018, Western Union quoted an approximately standard price of $6.95; so GTL clearly renegotiated their contract with Western Union to comply with the intent of the FCC’s order. (And GTL has never accepted payments via MoneyGram.) ↩

Companies are not powerless over their relationship with processors like WesternUnion. As we documented in 2013, companies can easily change the terms of their contracts with Western Union. ↩

Securus’ “single call” products often go by the brand names Instant Pay, PayNow, or Text2Connect; GTL often uses the brand names Collect2Card and Collect2Phone; and Telmate often uses the name QuickConnect. However, it would appear that the providers are currently rebranding these products and the names may therefore be changing. ↩

For example, GTL purchased Telmate in 2017. Telmate was a major competitor with two state prison contracts, a hundred county jail contracts, and (via subsidiary/partner Talton Communications) the contract for all United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facilities. That transaction gave GTL control of about 50% of the market and eliminated a major competitor in the valuable state prison market. ↩

The Prison Policy Initiative has joined other organizations in objecting to the Federal Communications Commission’s approval of the merger. Additionally, the Department of Justice is conducting an anti-trust investigation into the merger, according to Securus’ public letter to the FCC on October 18, 2018. ↩

PayNearMe is nationwide, including with locations in every CVS. To our knowledge, PayTel is the only prison/jail phone provider that currently accepts payment via PayNearMe. ↩

The New Jersey Department of Corrections lets county jails opt-in to its contract and most counties have done so. ↩

See https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-12-167A6.pdf ↩

And of course, to the degree that Chairman Pai believes that the FCC lacks authority to fully regulate this industry, he can support the Senator Duckworth's bill that would clarify that authority. ↩

Securus’s prepaid service is called Advanced Connect and GTL’s is Advanced Pay. For Securus, there were a few counties where prepaid rates were not available. For these counties, we used the Direct Bill price. ↩

Privacy policy

This report requests your location so that we can show the rates of phone calls in jails in your state. If you gave us this permission, we discarded your location data as the page finished loading. If you did not give us this permission — or if your browser was configured to decline permission automatically — this report simply makes an educated but unrecorded guess based on your IP address about what state’s data you will find most relevant.

Acknowledgements

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, and this report is no different, building on an entire movement’s worth of research and strategy. For this report, we wish to single out the contributions of illustrator Kevin Pyle for explaining two of the industry’s dirtiest and most complicated tricks in two comics, as well as Robert Machuga, Jordan Miner and Mack Finkel for their assistance with design and interactive functions. We also wish to acknowledge the editors at The Verge, who (in the excellent 2016 article Criminal Charges) gave us the inspiration for the phone rate clock in this report. We are also grateful to the many colleagues who helped us gather rate data, pointed us to documents on the history of companies in the prison and jail telephone industry, or reviewed drafts. The Prison Policy Initiative’s Communications Strategist, Wanda Bertram, provided invaluable feedback and editorial guidance. We also have to thank our individual donors, who choose to invest in research that gives voice to the 2.3 million Americans behind bars, and who make reports like this one possible.

About the authors

Peter Wagner is an attorney and the Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. He co-founded the Prison Policy Initiative in 2001 in order to spark a national discussion about the broader harms of mass incarceration. He is a co-author of a landmark report on the dysfunction in the prison and jail phone market, Please Deposit All of Your Money, and has testified in partnership with the Wright petitioners before the FCC in support of stronger market regulations. His other work includes the annual Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, groundbreaking research on the racial geography of mass incarceration, and reports putting each state’s overuse of incarceration into the national and international context. He is @PWPolicy on Twitter.

Alexi Jones is a Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative and a graduate of Wesleyan University, where she worked as a tutor through Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education. In Boston, she continued working as a tutor in a women’s prison through the Petey Greene Program. Before joining the Prison Policy Initiative in 2018, Alexi conducted research related to health policy, neuroscience, and public health. Her most recent publication is Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state (December 2018).

Compare another facility: or

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.