Going to bed hungry

For these families, every meal is now a struggle

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/XJEGVFR7A4I6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/I3UB44R6MUI6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/5CV63MSAOUI6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/3COPSDCAOUI6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/XQNBGJBZVUI6XKWZRFMSE4UAYQ.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/J2UGOSRZVYI6XKWZRFMSE4UAYQ.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/W4IGJDB7A4I6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/H33GYEB6MQI6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost/public/V7Z3TCB7A4I6XNMLCYR7MJTZMA.jpg)

Hunger is a hidden hardship that the pandemic has made visible, a persistent crisis that the pandemic has made worse.

Across America, people are lining up for food — on foot and in cars, at churches and recreation centers and in school parking lots, in wealthy states and poorer ones. They are parents and grandparents, students and veterans, employed and underemployed and jobless.

They often spend hours waiting for as much food as will fit in a box. They hope it will be enough to get them through the week, or the week after, when they will line up again for another box.

After months of deadlock, lawmakers passed a relief package in December with $400 million to help supply food banks. But billions in food aid expired at year’s end. The country’s largest network of food banks is bracing for a 50 percent reduction in food received from the government this year, even as demand soars.

In Pennsylvania and New Mexico, Maryland and California, The Post spent time with people living with hunger, and the people trying to help them.

Pennsylvania

This is Kelly Evans. She was a self-employed home health-care worker in the Pittsburgh area, until she caught the virus. She hasn’t had steady work since, or received unemployment. Most days she has five children to feed — a teenage son, an 11-year-old daughter and three grandkids, who stay with her while her eldest daughter, Kathryn, drives for DoorDash. Every meal is a struggle.

Evans’s daughter Kathryn Avitts spends 10 hours most days, and seven days most weeks, delivering meals. Sometimes she takes the kids with her, but they get tired after a few hours in the car. The $1,200 stimulus check last spring helped Avitts keep up with her bills for a few months, but now she’s behind again. The food stamps she receives are not enough to feed the family.

The local food bank only has enough supplies to offer pickups once a month, and the next-closest one is 45 minutes away. Getting there takes time Avitts can’t spend working and gas money she can’t afford.

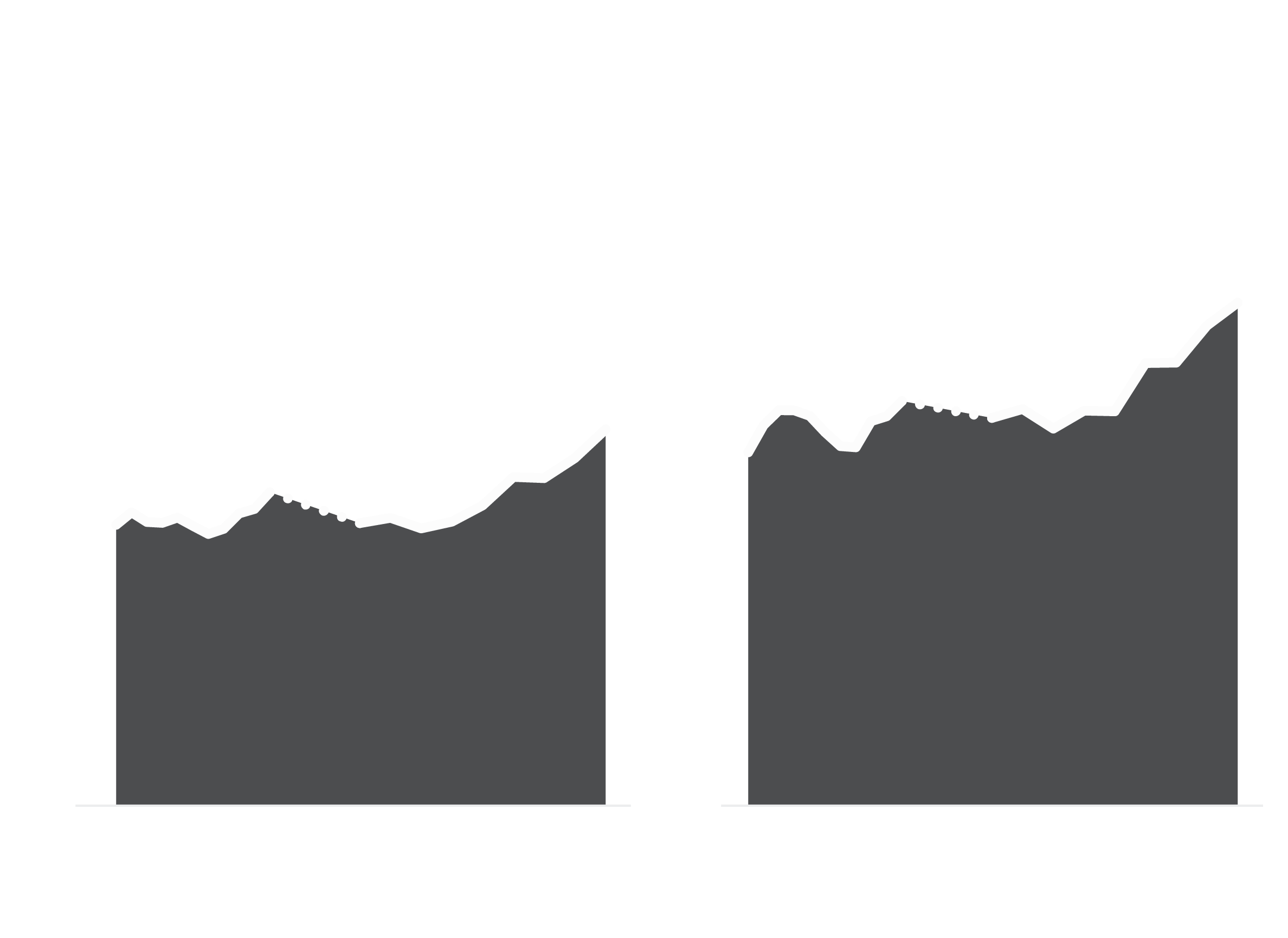

Nearly 30 million adults reported they sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last week, according to the latest Census Bureau data analyzed by The Post, more than at any time during the pandemic.

New Mexico

In many parts of New Mexico, fresh food is hard to come by, even in better times. You can drive for miles without passing a supermarket. If you don’t have a car, the local dollar store may be the only place to get groceries. The Food Depot is based in Santa Fe, but serves nine counties. It’s a lifeline for small, indigent communities, even more isolated during the pandemic.

For Justin Peters, the director of warehouse operations, sourcing the food is a constant challenge. He has to deal with donors, brokers, manufacturers and other food bank associations, all trying to keep pace with the need. He worries every day there won’t be enough to go around.

Murphy was living comfortably in Santa Fe, semiretired after a career as a paralegal. She had saved up for a trip to Egypt. The pandemic ended her travel plans, then it drained her savings. She’s always given to charity, and prides herself on being the person others turn to when they need a hand. Now, for the first time, she’s had to ask for help. She would only give her first name.

California

In Inglewood, Calif., in the heavily Latino neighborhoods near the Los Angeles airport, some 3 in 10 families live in poverty. Many people here have lost their jobs in the service industry; some are undocumented and don’t qualify for government aid. They can all turn to St. Margaret’s Center, which provides food every Wednesday to around 225 families.

For Juan Rosas, the weekly food box from St. Margaret’s has been one of the only constants in a time of uncertainty. He lost his job delivering food to hotels and restaurants. Now, his days are full of worry — about his four children’s struggles with virtual learning, about his landlord’s threats of eviction, and, most critically, about keeping his family fed.

Maryland

There is hunger, too, in affluent areas. In Takoma Park, Md., on the outskirts of D.C., hundreds of cars from across the region line up twice a month. Volunteers fill their trunks with food. When the day is done, they take a box home for their own families.

Among them is Theresa Nedd, an African American retiree on a fixed income who loves to cook for her six grandchildren — curry chicken, rice and peas, macaroni and cheese. “My son says, ‘You’re spoiling them, you need to stop,’ ” Nedd said. ‘“But I’m a grandmother, and that’s what grandmothers are for.”

A husband and wife set up the food distribution, piecing together grants and donations. Smith Kwame Oliver Vodi and Yvonne Reginat Vodi, founders of Shepherds of Zion Ministries International Church in Silver Spring, Md., poured their energies into feeding people after the pandemic forced a halt to services.

Hunger is tightening its grip on America. It is an empty fridge in New Mexico, a skipped meal in Pennsylvania, an unpaid bill in California, a line of cars just outside the nation’s capital.

One in 7 adults say their households don’t have enough to eat.

President Biden has increased funding for food stamps and school lunches, and he has proposed nearly $2 trillion in new economic relief.

For families in need, it can’t come soon enough.

Scroll to continue