The New Right’s Strange and Dangerous Cult of Toughness

An emerging culture idolizes a twisted version of “toughness” as the highest ideal and despises a false version of “weakness” as the lowest vice.

Last month, at the National Conservatism conference, a gathering of hundreds of leaders and members of a movement that hopes to represent a new, less libertarian American right, one of the speakers, a lawyer named Josh Hammer, delivered a strange denunciation of “fusionism.” For those not steeped in the language of conservatism, fusionism refers to the alliance among economic conservatives, social conservatives, and defense hawks forged during the Reagan administration. It was designed to confront government overreach at home and the threat of Soviet tyranny abroad.

Fusionism, Hammer said, is “inherently effete, limp, and, as Hillsdale College’s David Azerrad might say, unmasculine.” It “makes for a cowardly way to approach politics” in part because it “ensures never having to face pushback from one’s political opponents on the most contested issues.”

Longtime fusionists, who are veterans not just of the intense and consequential debates surrounding foreign policy during the Cold War and the War on Terror but also of countless successful courtroom contests designed to expand First Amendment rights in the face of government censorship, might be startled by this news.

But that’s hardly the oddest part of Hammer’s critique. Fusionism is “unmasculine”? How is that claim a part of an allegedly serious ideological argument? The critique, however, helps illuminate the emerging culture of the right—a culture that idolizes a twisted version of “toughness” as the highest ideal and despises a false version of “weakness” as the lowest vice.

Claims of cowardice have particular purchase among Trump’s followers. Coward is a one-word rebuttal that not only attempts to end an argument, but also aims to discredit the person who made it. Who wants to listen to a coward? Who wants to be known as a coward?

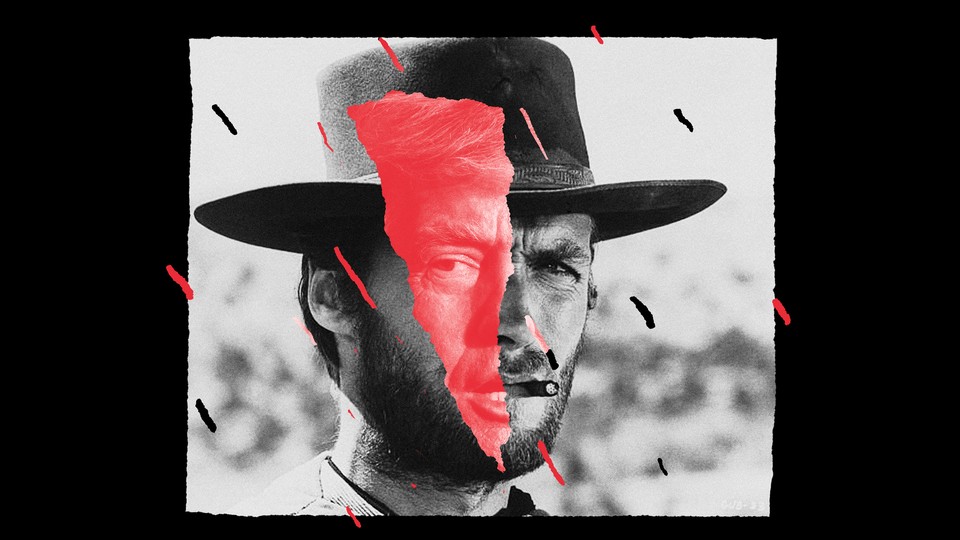

What makes the claims of toughness and weakness especially curious and dangerous is the way in which they’re tied to the person of Donald Trump. Although “toughness” has long been a populist virtue—especially in the South—the age of Trump transformed the right’s definitions of strength and courage by reference to the man himself. And what are Trump’s alleged strong, masculine virtues?

In the Azerrad essay that Hammer cited, Azerrad explains that Trump’s strength is “not that of a soldier who risks his life in combat or of a general who leads men into battle.” (Trump used an alleged diagnosis of bone spurs to avoid the draft during the Vietnam War.) So in that sense, Trump “isn’t as manly as” General Jim Mattis, Azerrad concedes. But Trump is more manly than Mattis in a different way, he explains: “Trump’s manliness is that of a man who is not afraid to say out loud what others only whisper and to incur the wrath of the ruling class for doing so.”

This is a curious definition of manliness. Saying what you think or what others seem afraid to say isn’t inherently “manly.” Speaking your mind isn’t even inherently virtuous, much less inherently masculine. Trump has said many false and harmful things, and the fact that other people might whisper them does not mean that they should be shouted from the presidential bully pulpit.

When Trump’s supporters claim that he is tough and manly, though, they’re often also trying to flatter themselves by implying that they share his virtues. In an apology written to Never Trumpers after the January 6 attack on the Capitol, the evangelical intellectual Hunter Baker expressed a common view. Never Trumpers, he said, “struck me as psychologically and emotionally weak people with porcelain-fragile sensibilities.”

The weakness/strength dichotomy works as shield and sword. Any critique of Trump, Trumpism, or the new right can be dismissed as evidence of mere cowardice or fragility. The Never Trumpers and classical liberals aren’t strong enough for the fight, the new right tells itself. Rather than doing what it takes to stand against the left, they retreat to the shelter of “elite” spaces, where the left welcomes them with open arms.

And what of the “strength” of Trumpism? Because the movement is centered on and modeled after Trump himself, many of these displays of “strength” are deliberately cruel (see, for example, Adam Serwer’s seminal essay, “The Cruelty Is the Point”) and deliberately defy moral norms. Indeed, the cruelty itself is an act of defiance—decency is what “they” demand, and one cannot comply with “their” demands.

This defiance of moral norms means that Trumpist “toughness” was never, and could never have been, truly confined to online spaces or even to tough rhetoric. Boundaries are for the weak. So while Trump’s new-right allies and successors often treat Twitter as their Omaha Beach and angry tweets and vicious insults as the online equivalent of attacking a German pillbox with rifle fire and grenades, others know that becoming a keyboard warrior is hardly the highest masculine ideal.

Indeed, the logic of the movement presses toward direct action. If you tell enough people that the future of the country is at stake, that their political opponents have corrupted democracy, and that only the truly tough have what it takes to save the nation, then speeches about unmanly ideologies will never be enough. Trolling on Twitter will, ironically, come to look like a hollow remedy, itself a form of weakness.

Thus we see the increased prevalence of open-carried AR-15s at public protests, the increased number of unlawful threats hurled at political opponents, and outbreaks of actual political violence, including the large-scale violence of January 6.

One of the most dangerous developments in our contentious times has been a growth in radical ideologies bolstered by radical intellectuals who often treat decency and even peace as impediments to justice. The riots that ripped through American cities were inexcusable expressions of political fury (and sometimes pure nihilism) that were too often rationalized, excused, and sometimes even celebrated. The author and academic Freddie deBoer has compiled a depressing list of articles, essays, and interviews in prominent publications excusing and justifying violent civil unrest.

The right-wing cult of toughness, in its distinctly Trumpist version, is no exception to this trend. When it is drained of limiting principles and tied to a man who would rather seek to upend our nation’s constitutional order than relinquish power, then the threat to the republic is plain. That threat will remain until the supposedly weak classical liberals on the left and the right do what they’ve always done at their best—rally in defense of liberty, the rule of law, and the American order itself.