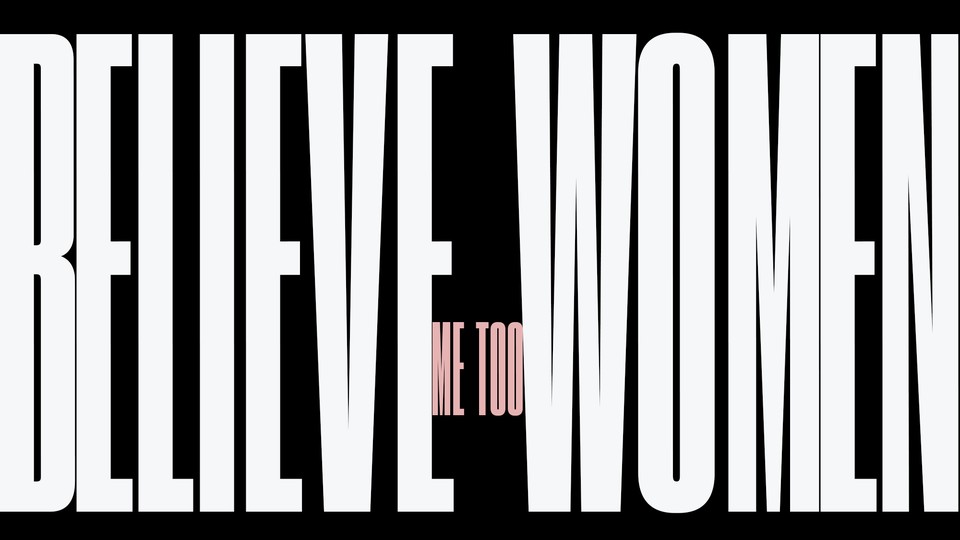

Why I’ve Never Believed in ‘Believe Women’

The Biden allegations reveal the weakness of the #MeToo movement’s rallying cry.

Imagine that a friend tells you they have been sexually assaulted. What do you do? Your first reaction would, I hope, be sympathy. You would not pepper them with questions: what were they wearing, what were they drinking, what were they thinking? You’d believe them.

Now imagine being a human-resources manager. In front of you is an employee making a claim of sexual harassment against a colleague. Your duty is to ensure the employee’s well-being—but also to decide whether to conduct a formal investigation. You might point them toward counseling resources, but also ask if there is evidence to back up their version of events.

Now you’re a journalist. A woman has just come to you alleging that she was sexually assaulted by a public figure. Your response here is the opposite of a friend’s reaction. You ask about corroboration: letters, answering-machine messages, witnesses, emails, photographs, dates, times. You look for the weaknesses in the story, the omissions, the contradictions. You remember the journalist’s maxim If your mother says she loves you, make her prove it. You do not simply “believe women.”

That’s because “Believe women” isn’t just a terrible slogan for the #MeToo movement; it is a trap. The mantra began as an attempt to redress the poor treatment of those who come forward over abuse, and the feminists who adopted it had good intentions, but its catchiness disguised its weakness: The phrase is too reductive, too essentialist, too open to misinterpretation. Defending its precise meaning has taken up energy better spent talking about the structural changes that would make it obsolete, and it has become a stick with which to beat activists and politicians who care about the subject. The case of Tara Reade, who has accused the presidential candidate Joe Biden of sexual assault, demonstrates the problem.

In the two and a half years since the first wave of #MeToo allegations, scores of famous and non-famous women (and fewer men) have come forward with experiences of sexual harassment, assault, and rape. There have been “cancellations,” job losses, and convictions. There have also been edge cases, uncomfortable gray areas, and men who have said their lives were ruined by nebulous allegations. “Believe women” was intended to capture an undeniable truth: Sexual harassment and sexual assault are so endemic in society that they make the coronavirus look like a rare tropical disease. False allegations do exist, but they are extremely uncommon. (Men are more likely to be raped than falsely accused of rape.) When thousands of women tell us that there is a problem with sexual aggression in our society, we should believe them.

That broad truth, however, tells us nothing about the merits of any individual case. And as my colleague Megan Garber has written, “Believe women” has evolved into “Believe all women,” or “Automatically believe women.” This absolutism is wrong, unhelpful, and impossible to defend. The slogan should have been “Don’t dismiss women,” “Give women a fair hearing,” or even “Due process is great.” (Or, you know, something good. Sloganeering is not my forte.) Why did “Believe women” catch on? Possibly because it is almost precision-engineered to generate endless arguments about its meaning, and endless arguments are the fuel of the attention economy otherwise known as internet, newspaper, and television commentary.

As a rallying cry, “Believe women” groups cases together in a deeply unhelpful way. In a court of law, there are grades of offense, and sliding penalties. In the court of public opinion, we talk about rape and a hand on the knee in the same breath. A man who becomes “#MeToo accused”—but whose case is never publicly aired in full—carries a miasma of unspecified wrongdoing. And if there is no possibility of “serving your time,” all the incentives point toward denial rather than confession.

Each new case tends to be read through other, typically unilluminating, reference points. It is hard to find an opinion about Reade that is not also one about Christine Blasey Ford, who publicly accused Brett Kavanaugh of attempted rape when he was nominated by Donald Trump to the United States Supreme Court. (Kavanaugh denied the offense, and he was confirmed.) “Believe women” lumps Reade and Blasey Ford together, demanding that politicians, the media, and observers treat their stories exactly the same. After all, they’re both women, aren’t they?

But the cases are not the same, neither in their details nor how they came to light. Laura McGann at Vox writes that she was one of several mainstream journalists approached by Reade in April last year, and tried hard to corroborate her original allegation—that Biden touched her on the neck and shoulders in a way that made her uncomfortable—but failed. Others did too. Those journalists did not “believe” or “disbelieve” Reade; they didn’t find enough evidence to publish anything close to a definitive account. “If I were an old friend of Reade’s and she told me this same story privately over the course of a year, I doubt I would question her account,” McGann notes. “But I’m not an old friend. I’m a journalist.” The New York Times’s executive editor, Dean Baquet, made a similar point in a spiky interview with his paper’s own media columnist. (Reade later found a hearing among journalists and outlets that have been critical of Biden, and broadened her allegations to include sexual assault. These claims have now been conscripted into the case for ditching Biden as the Democratic nominee in favor of Bernie Sanders.)

One of the hardest #MeToo arguments to make is that sometimes the role of journalists is not to publish, out of fairness to accused men as well as their accusers. It is cruel to expose complainants to the searchlight of publicity when their allegations are flimsy, or to write stories in which inconsistencies are not confronted. Doing so is asking for the accuser to be disbelieved, and that experience can be re-traumatizing.

“Believe women” therefore makes the job of journalists more difficult. It has made necessary skepticism look like hostility. Sources should know that reporters are only asking hard questions because everyone else will. Many interviewees, on any type of story, will offer a version of the past buffed up in numerous tiny ways to make them look better, unaware that they have done so. Being drunk or high doesn’t mean your allegation is not credible, for example, but if those facts are excluded from the initial story, only to be revealed later, your whole narrative will be considered “debunked.” The damage of publishing a story that unravels is huge, not just to the individuals involved, but to the issue of sexual assault as a whole. For instance, gang rape is a real and horrifying phenomenon, but for many people, the sole story they will have heard about it is Rolling Stone’s now-retracted report “A Rape on Campus.”

By and large, it is the liberal left that has adopted the “Believe women” mantra; and, like a gun kept in the house, a weapon of such power is most liable to injure its owner. It provides feminists with no way to rebut or question any particular story without being accused of hypocrisy, turning every marginal case into a “gotcha.” Female politicians get burned both ways: They face angry demands to disassociate themselves from accused men, and equally angry accusations of knee-jerk man-hating if they do. (The case of Senator Al Franken is a sorry tale of well-meaning people feeling the need to decry instantly rather than investigate fully.) As Moira Donegan has noted, female Democrats “have been tasked with cleaning up the mess” from Reade’s allegations. Biden has pledged to pick a woman as his running mate: Expect her to take as much heat on the subject as he does, if not more.

Why has #MeToo become fixated on questions of belief? Because in too many cases, belief is all we have. The worldwide outpouring of traumatic experiences has not led to the structural changes needed to arbitrate claims in anything close to an objective fashion. Instead, in the U.S. and elsewhere, cases are decided along partisan lines. It was painful to read the section of She Said, the book by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, which deals with the Blasey Ford allegations. Here was a woman who tried to do everything right. And then, faced with a Republican artillery barrage, she took refuge in the only place she could, relying on Democrats to champion her cause in the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings. There was never a neutral forum in which her story could be heard.

This is the final failure of “Believe women,” and demonstrates why it was a mistake to let the slogan take hold. In its needless, provocative overstatement, it derails the #MeToo conversation, and prevents it from moving to the question of how to change structures. If belief is fairy dust, we can simply sprinkle that on women and not worry about the institutions that are letting them down. HR departments too commonly exist to protect companies, not their employees. Serial predators go uncaught because untested rape kits lie piled up in warehouses. Complainants are subjected to a “digital strip search,” and cases are dropped if they won’t allow police to rifle through their data. It is impossible for women to expect justice from a system such as this.

In Britain, an outside lawyer was asked to produce a report on Parliament’s failure to deal with bullying and harassment by powerful politicians. Her recommendations included a confidential helpline, and an independent complaints procedure. This is a promising start: From famous actors to cleaners on short-term contracts, from political staffers to delivery drivers managed by an app, the world of work is more and more fragmented and casual, and new channels for complaints must be created. For criminal allegations to be pursued thoroughly, police forces need to look like the communities they represent, and they need to prosecute sexual offences with sensitivity and rigor. Rape cases are often mentally filed in the “too difficult” box: The attrition rate as they move through the police, prosecution, and the courts is high.

Yes, believe that sexual harassment and assault are far more widespread than we have ever been willing to acknowledge. Believe that “nice guys,” even self-identified feminists, are capable of treating the people around them like dirt. Believe your friends when they are asking for nothing more than your support.

But do not confuse any of that with an injunction to believe any single woman’s public allegation, without caveats, without questions. “Believe women” is a bad slogan, and it should be retired. We should not be expected to believe women. We should instead be able to believe in the system.