Robert Adams is one of the most important trailblazers of modern American photography; a key figure in the New Topographics movement (a term coined by William Jenkins to describe the visual documentation of "man-altered landscapes"), he revolutionised the way in which the American West was depicted on film, highlighting the effects of industrialisation upon what was once a vast, imposing wilderness that would have made Lord Byron swoon.

Born in 1937, in Orange, New Jersey, Adams' family relocated to Wheat Ridge, Colorado, a suburb of Denver, when he was 12. Adams spent much of his childhood and adolescence hiking and mountain climbing – a passion which stuck with him into adulthood. Having majored in English, it wasn't until 1963, at the age of 26, that Adams bought a 35 mm reflex camera and began photographing nature and architecture. His fascination with the medium burgeoned, and – after a fortuitous meeting with John Szarkowski, the curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in 1969, which resulted in MoMA's purchase of four of his prints – he opted to pursue his passion full-time.

Adams' monochrome style – at once formal and evocative – was influenced by 19th-century photographers like Timothy O'Sullivan, William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkin, who also focussed on the landscape of the West (in its more primitive state) as well as Lewis Hine, Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams, all of whom married social and aesthetic concerns in their work.

The turning point in Adams' career was the publication of his highly acclaimed photo-essay, The New West, in 1974, which catapulted the image-maker into the public eye. Divided into five sections, the book takes us along the front wall of the Colorado Rocky Mountains, presenting a representative sampling of the entire suburban Southwest. We are first confronted with two, light-drenched images of sprawling prairies, where the only sign of human intervention are electricity pylons and wooden fence posts. Then these open fields are shown bearing signs, first: No Trespassing, then: For Sale or Lease, and you begin to feel the shadow of commercial opportunism ominously approaching. Sure enough, the next section depicts the rapidly growing expanse of tract houses and mobile homes popping up along the Front Range, breaking us in with an image of the foundations of a single tract house being laid in a sparse stretch of land, before presenting us with an entire town of these compact white abodes, which nevertheless appear tiny and somehow insignificant against the backdrop of the towering mountains and an omnipresent sky.

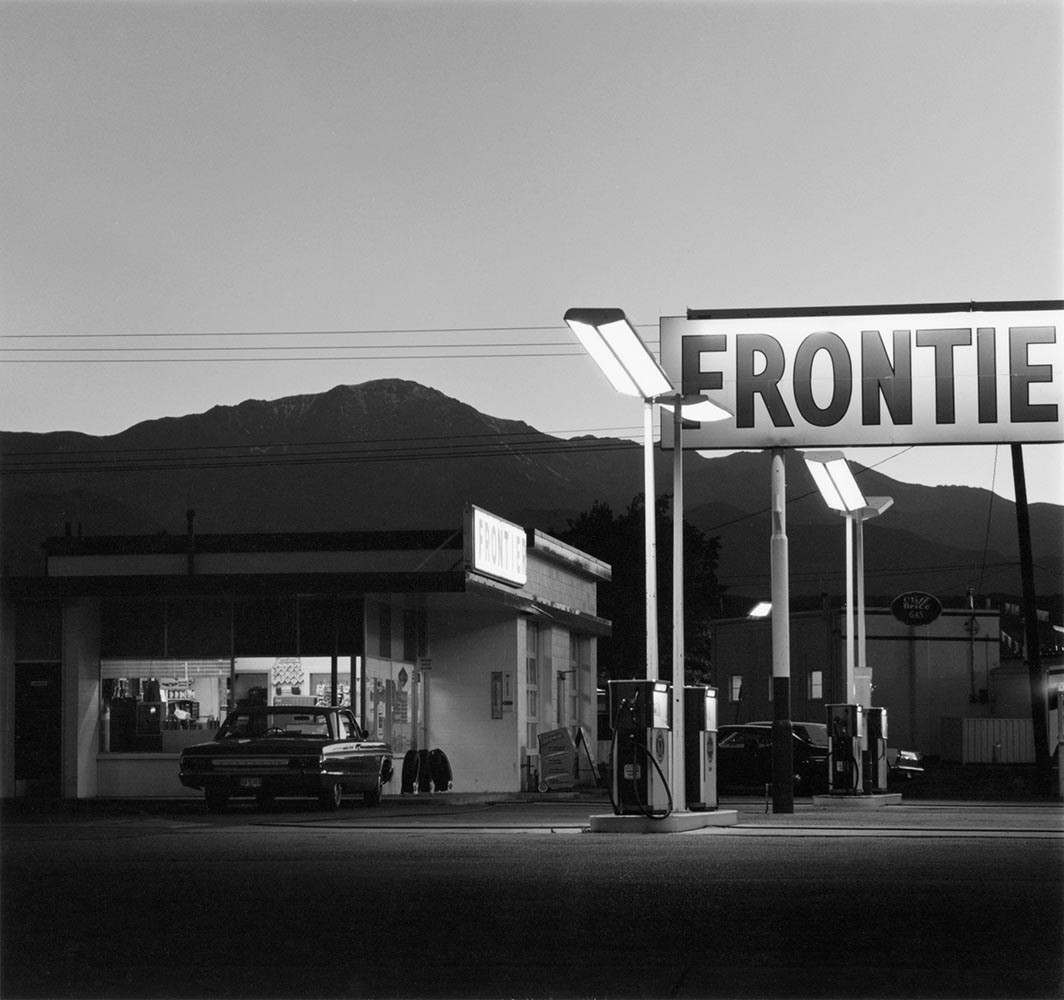

Depicting the unwavering presence and beauty of nature in the face of human intervention was, for Adams, a key element of the project. As he explains in the book's introduction, "Why open our eyes anywhere but in undamaged places like national parks? One reason is, of course, that we do not live in parks, that we need to improve things at home, and to do that we have to see the facts... Paradoxically, however, we also need to see the whole geography, natural and man-made, to experience a peace; all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolute persistent beauty." And indeed, even when Adams zooms in on the man-made – be it a woman strikingly silhouetted between two windows of her neat brick bungalow, a packed Denver carpark or a peak-side gas station, complete with enormous sign – there is an inherent, inescapable allure, stemming from the photographer's aptitude for composition and ability to encapsulate the atmospheric quality of light so unique to the area. "The subject of these pictures," his introduction continues, "is not (...) tract homes or freeways but the source of all Form, light. The Front Range is astonishing because it is overspread with light of such richness that banality is impossible."

This month marks the re-release of Adams' seminal work by Steidl and with it the opportunity to ponder on the positive, and instructional nature of his message. We all need to open our eyes to the impact of our actions and the effects of industrialisation on our planet – today more than ever – because if we stop and acknowledge these things, as Adams writes, "then we know, safe from the comforting lies of profiteers, that we must begin again." Equally, through his exceptionally executed, deeply poetic works, we are reminded that we – with our limited life spans and endless aspirations – pale in comparison to the longstanding landscapes that surround us. "Though the mountains are no longer wild," writes Adams, "they still dwarf us and thereby give us the courage to look at our mistakes – expressways, Tyrolean villages, and jeep roads. Such things shame us, but they cannot outlast the rock; in sunlight they are, even for a moment, like trees." This powerful sentiment is embodied by the book's final image – a mountainside cemetery whose small, greying gravestones populating the grassy plot they inhabit, mirror the pine trees dotted across the mountain slope above them.

The New West is out now, published by Steidl.