As a wind swept leaves past the steps of the Kenosha county courthouse last week, the streets were sparsely trafficked as another day of proceedings came to a close in the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot three people last year, wounding one and killing two.

The muted scene around the courthouse stood in stark contrast to the chaotic scene that played out in the Wisconsin city on the night of 26 August 2020. And it belied the scale of what is at stake for Rittenhouse, his victims, and their family members, and for America as a whole, as it faces yet another legal reckoning over racism, rightwing politics and policing.

“The past year has been a living hell for the family,” said Justin Blake, the uncle of Jacob Blake, who in August 2020 was shot seven times in the back by a Kenosha police officer and left paralyzed from the waist down.

“To see your loved one, someone you helped raise and take to the ballpark and make a good young man out of, to see the video of him shot like that, it takes your breath away. I can’t even watch it any more,” Blake said from the steps of the courthouse.

While Rittenhouse stands accused of six criminal counts, including homicide, much more is on trial in the court of public opinion: the police shooting that set off the protests, selective enforcement of laws, and a justice system that incarcerates Wisconsin’s Black residents at a higher rate than any other state in the nation.

Racial justice advocates say any verdict will not resolve long-simmering racial tensions that boiled over last August. But Kenosha as a community must find a way to move forward regardless of the outcome.

For Blake’s family, the past year has in some ways been framed by gunshots and two videos depicting two wildly divergent responses from police. In one video, Blake, who carried no gun, was shot multiple times in front of his children.

In another, Kyle Rittenhouse, now 18, is seen trotting past police, assault rifle slung over his shoulder, as bystanders identified him as the shooter. Police did not intervene as Rittenhouse left the scene.

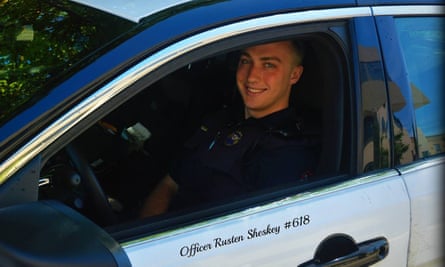

Last month, the US Department of Justice announced that the officer who shot Blake, Rusten Sheskey, will not face any federal criminal civil rights violations. By then, Wisconsin prosecutors had already cleared Sheskey of state criminal charges.

Adelana Akindes, a 26-year-old activist who grew up in Kenosha, said she was not surprised by the response from authorities in the wake of the police shooting and the ensuing protests.

She described Kenosha, a majority-white rust belt city of 100,000 that sits between Milwaukee and Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan, as the kind of place where drivers of color are profiled by police and the sheriff calls for lawbreakers to be “warehoused” for life so “so the rest of us can be better”.

“It’s a racist place,” she said. “Not always outwardly so. But you can look at the people in power and see it,” pointing to the sheriff’s comments.

The night of the deadly protest, former Kenosha city council member Kevin Mathewson put out a call on Facebook asking the Kenosha Guard rightwing militia group and other armed civilians to protect lives and property. Within minutes, the Kenosha Guard leapt into action.

Akindes, who identifies as Black, said activists in Kenosha had historically been slow to mobilize, but when video emerged showing police shoot Blake in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, people took to the streets.

“Everyone had a very visceral reaction,” she said. “This type of uprising doesn’t usually happen in Kenosha, but it was an escalation of the tensions that were already building. It was amazing to see how many people turned up to support Blake.”

Akindes said the night of 26 August, she and several other activists were on their way to join a larger demonstration when two unmarked cars swerved into her path. Officers bound her hands, arrested her and took her to a detention center for violating curfew. She wasn’t released until the next day.

Akindes is a named plaintiff in a lawsuit filed in federal court that alleges law enforcement targeted demonstrators protesting police brutality. More than 150 peaceful protesters were arrested over the nine days of demonstrations, according to the suit – not a single one of them pro-police or members of armed militias.

“In Kenosha, there are two sets of laws,” reads the complaint. “One that applies to those who protest police brutality and racism, and another for those who support the police.”

Videos that surfaced after the night of protests reinforced that perception. One video captured police on patrol the night of 26 August providing water and expressing support for armed militia members. “We appreciate you guys, we really do,” one officer said.

Rittenhouse became a cause célèbre in some rightwing circles, with the Fox News host Tucker Carlson hailing him as someone who “had to maintain order when no one else would”. Fundraising generated hundreds of thousands of dollars to his defense fund. A data breach revealed a list of donors who contributed, including public officials and Wisconsin law enforcement officials.

“Stay strong brother,” wrote one donor whose email account was connected to a law enforcement officer in Pleasant Prairie, seven miles west of Kenosha.

Kim Motley, an international human rights and civil rights attorney, said she saw a disturbingly “cozy” relationship between police and armed militia groups that led to selective enforcement laws the night of 26 August.

Motley is representing Akindes in a class-action lawsuit that accuses Kenosha law enforcement of constitutional violations. In asking the court to dismiss the lawsuit, the city said its enforcement helped curb “rioting, mayhem and attacks” during the uprising and were thereby justified.

Separately, Motley is representing Gaige Grosskreutz, who Rittenhouse shot in the arm, in a suit that alleges law enforcement officials condoned the efforts of white nationalists to use violence against those protesting police brutality.

The attorney representing Kenosha county and Sheriff David Beth said in a statement that the allegations against his clients were false and failed to “acknowledge that Grosskreutz was himself armed with a firearm when he was shot and Grosskreutz failed to file this lawsuit against the person who actually shot him.”

Motley said she sees a real “us-versus-them mentality” from law enforcement in Kenosha.

“I’m from this part of the world. And there has always been a real warrior mentality with the policing that I see in Kenosha county,” she said. “It seemed like police were giving a wink and a nod to militia members that night. I don’t think they wanted anyone to die, but certainly I think there was implicit support for people like [Rittenhouse] to act like law enforcement and to impose punishments as they saw fit.”

Motley said the complicity that appeared to exist between police and militia members set the stage for what was to come.

“Frankly, I feel like Kenosha was training for what happened at the US Capitol.”

With so many issues converging in one case, the concept of justice depends on the perspective of victims. But at the very least, she said, it would include an accounting for the actions taken that night. And it would involve attempts from the city and police to reach out to the community to begin the healing process.

“At the end of the day, there’s only so much police can do. And there’s only so much community members can do. But if neither side is willing to reach across the aisle, it’s just going to be worse,” she said.

Kenosha councilman Jan Michalski, who represents the Uptown neighborhood that experienced much of the damage from the protests, said the city has taken steps toward healing through listening sessions the mayor has led and efforts to support activists that can serve as violence disruptors across the city.

Many of the Uptown storefront windows are still boarded as the community worries over the reaction to the coming verdict. But Michalski said people have come together to rebuild the area and neighborhood development plans are under way.

“The trial has divided folks, certainly. And it’s been hard to tamp down the anger with all the publicity we’ve gotten. But the city of Kenosha is full of good people. People want to feel safe from crime, and also safe from police. And I think that’s a reasonable position,” he said.

For Bishop Tavis Grant II, who accompanied Justin Blake to the courthouse, the verdict in the Rittenhouse trial is only the beginning of a longer march toward justice.

“When we talk about people who don’t have access to capital, access to healthcare, people who don’t have access to the American dream, this is just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

“In all reality, this is not an answer or panacea. No matter what the verdict is, we’ve still got a hell of a lot to fight for, and fight about.”