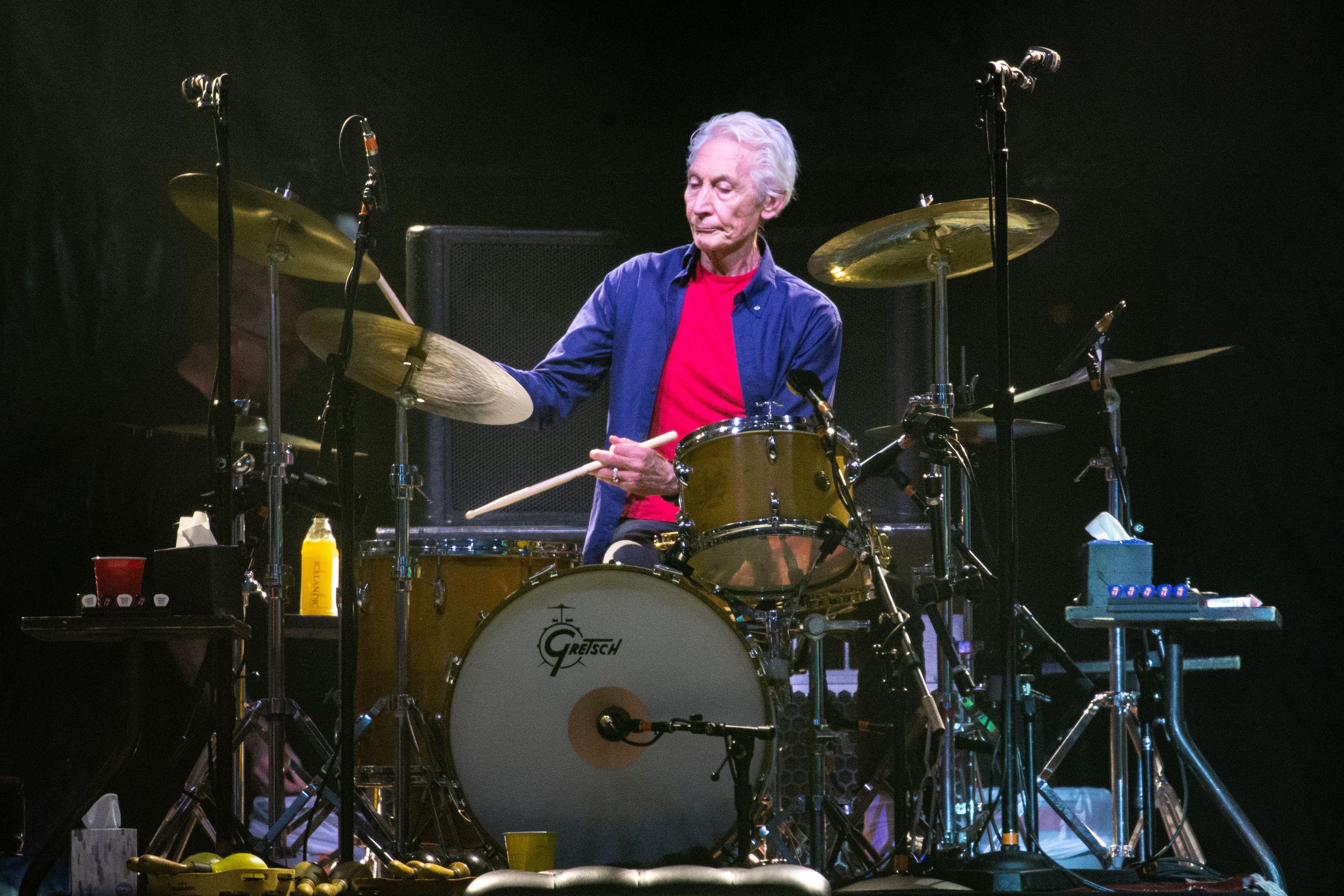

Charlie Watts, the irreplaceable Rolling Stone who died on Tuesday at age 80, wouldn’t have been anyone’s pick for the world’s most technically accomplished drummer. His chops were fine but unremarkable; his sense of time would never be mistaken for a metronome. It speaks to the wonder of music, and rock ’n’ roll music in particular, that these objective shortcomings were, in fact, crucial to what made him so great. Charlie Watts was a drummer whose whole musicality so vastly exceeded the sum of its parts, an outsize part of the soul of the greatest rock ’n’ roll band in the world.

The Rolling Stones released their first recordings in 1963, at a time when rock ’n’ roll and rhythm and blues were, from a musical standpoint, still mostly indistinguishable from each other. Watts was a jazz player first and foremost, who would become, probably for this reason, the greatest British R&B drummer who ever lived. His playing had a swinging and improvisational ease to it, the sound of a man intuitively feeling his way through whatever music was happening before him. As a self-fashioned jazzman, Watts also wasn’t laboriously trying to imitate American blues drummers like Fred Below and Sam Lay, which freed him from the anxiety of influence that stalked many young performers of the British blues scene of the early 1960s—including some of members of his own band.

The creation of the Beatles, the Stones’ great rival and frequent point of comparison, is often spoken of in terms of divine providence: How could four guys that talented manage to find one another as teenagers, in Liverpool of all places? Those questions don’t tend to come up as much about the Stones, five Londoners that mostly connected from having already played in other groups. But there is something equally astonishing about the fact that Charlie Watts and Keith Richards, possessors of two of the most inimitable rhythmic sensibilities in human history that are entirely unique and yet perfectly complementary to each other, ended up in the same band. Drummers are often described as a band’s “heartbeat,” which may imply that other musicians are the cerebellum, but in the Stones that metaphor was precisely the opposite: Keith was the band’s beating heart, pulsing and relentless, whereas Charlie was the brains of the operation, taking that rush of blood and converting it into wit, style, and cool.

When the Rolling Stones first truly arrived with 1965’s “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”—the band’s first trans-Atlantic No. 1, and their first single that felt singularly like the Rolling Stones—Charlie was the engine that drove it there. His drum parts on subsequent hits like “Get Off of My Cloud,” “Paint It Black,” and “Mother’s Little Helper” are dazzling feats of musical energy, all propulsive, clamoring motion. Many of the Stones’ mid-’60s recordings were clumsily produced affairs—Andrew Loog Oldham was no George Martin—but the resultant sonic morasses give these recordings a peculiar power all their own. Charlie’s drums sound like tidal waves; all you can do is hang on. The Stones were already much more accomplished than what would soon come to be known as a “garage band,” but they damn sure sounded like they were playing in a garage, and they helped create a new kind of musical imagination. “The first Velvet Underground album only sold a few thousand copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band” is a cute quote, until you think about just how many people fitting that same description probably bought “19th Nervous Breakdown.”

After a disastrous 1967, the Stones dropped Oldham and hired Jimmy Miller, an American producer who was light-years better at his job than his predecessor and also, crucially, a drummer. Miller’s first production for the Stones was the 1968 “comeback” single “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”; his subsequent work on LPs from Beggars Banquet (1968) to Exile on Main St. (1972) remains the band’s artistic high-water mark and, in my estimation, one of the greatest runs in the history of recorded music. It’s barely an exaggeration to say that the Rolling Stones reinvented rock ’n’ roll music in this period, returning to Chuck Berry’s original architecture and updating it into a loud, riff-driven, swaggering beast that brusquely nudged the music away from both psychedelic pomp and pop sheen and toward the harder and more aggressive sounds that would define much of rock in the 1970s.

Like everyone else in the Stones, it was during the Miller era that Charlie came into his full musical fruition. For a band that was effectively inventing arena rock, the Stones were never much prone to bombast, and Charlie least of all. Part of the magic of the Stones in this period was that the band was writing such deliberately tasteless songs and yet playing them so irresistibly tastefully. On 1968’s incendiary “Dancing in the Street” rewrite “Street Fighting Man,” Charlie provides a world-class R&B backbeat, rock-solid and utterly confident; his performance on the satanic travelogue “Sympathy for the Devil” is a masterpiece of effervescence and insinuation. (Watts later told an interviewer that his “Sympathy” work was inspired by Kenny Clarke’s playing on the bebop classic “A Night in Tunisia.”) I don’t know that a recorded drum has ever sounded better than Charlie’s double-snare-hit entrance on “Let It Bleed,” which comes a mere 13 seconds into the song but still manages to completely transform it.

There’s something impossible and unfathomable about the Rolling Stones in this period, like DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak if Joltin’ Joe were writing songs about dope sickness and serial killers. Even 50-plus years on, listening to the Stones’ 1968–72 records frequently turns me into Jesse Pinkman, howling to the heavens “they can’t keep getting away with it!” Keith transforms from an ace rhythm guitarist into a full-fledged musical genius; Mick goes from a guy who preferred singing covers to one of the greatest songwriters on earth. Through it all, Charlie remains the center of gravity: On Sticky Fingers, tracks like “Sway,” “I Got the Blues,” and “Moonlight Mile”—songs so audacious in their depth and ambition they would have been inconceivable for this band only a few years earlier—only cohere because Charlie knows just how to pull them together, the perfect part to play, the perfect tempo, the perfect feel.

Any discussion of the Rolling Stones can’t help but find its way to the band’s 1972 double-LP Exile on Main St., an album so steeped in lore it can sometimes risk drowning out itself. I don’t know if Exile is the best Rolling Stones album, but it’s certainly the most Rolling Stones album, and as such, it contains a sizable handful of Charlie’s very best performances. Among these is “Tumbling Dice,” a song that, gun to my head, probably gets my vote as the greatest recording this band ever made.

“Tumbling Dice” is soul music at its highest level, one of those moments when you hear the Rolling Stones become everything they once worshipped. Everything about it is ragged and flawless, the song, the performances, the arrangement, the mix, the vocal interplay between Jagger and Keith and the backup singers and, of course our man himself, Charlie Watts, who lays down a groove so beautiful that it has more than once moved me to tears, especially lately. It’s a drum part that floats and dances, generative and responsive and graceful and authoritative and impossibly laid-back. You can’t learn to play music like this; you’re born with those ears or you’re not. No one will ever play drums like Charlie Watts, the perfect drummer in what was, once upon a time, the perfect band.