‘I Was Responsible for Those People’

The manager of Windows on the World survived 9/11, while 79 of his employees died. He’s still searching for permission to move on.

Updated at 11:30 a.m. on September 10, 2021.

On the evening of September 4, 2021, one week before the 20th anniversary of 9/11, Glenn Vogt stood at the footprint of the North Tower and gazed at the names stamped in bronze. The sun was diving below the buildings across the Hudson River in New Jersey, and though we didn’t realize it, the memorial was shut off to the public. Tourists had been herded behind a rope line some 20 feet away, but we’d walked right past them. As we looked on silently, a security guard approached. “I’m sorry, but the site is closed for tonight,” the man said.

Glenn studied the guard. Then he folded his hands as if in prayer. “Please,” he said. “I was the general manager of Windows on the World, the restaurant that was at the top of this building. These were my employees.”

The man glanced over Glenn’s shoulder. “Which ones?”

Glenn didn’t say anything. Slowly, he turned and swept his open palm across the air, demonstrating the scale of the devastation: All 79 names were grouped together. The guard closed his eyes. “Take as much time as you need,” he said softly.

Here, I should pause to explain something: Glenn is my cousin. I was a high-school sophomore in September 2001; my mother was driving me to an orthodontist appointment when the North Tower collapsed. She thought her nephew was dead, only to find out hours later that he wasn’t. For the next two decades, Glenn and I scarcely saw each other, and when we did, I never asked about 9/11. But we grew closer these past couple of years—sparked by my father’s death, and a bar scrap we got into a few nights before the funeral, with multiple guys holding Glenn back from pummeling some drunken loudmouth—and I grew more curious. When I asked if I could spend time with him in early September, Glenn, who is 61, responded enthusiastically. “Maybe it will help me,” he said. I wanted a story. He wanted catharsis.

Glenn’s mother and my father were born into a broken, dysfunctional Sicilian clan in Bergen County, New Jersey. The patriarch, our grandfather, Frank Alberta, ran an eponymous restaurant that was a hangout for mafiosos, businessmen, and the occasional ballplayer. Glenn wanted nothing to do with the family legacy of violence and rage and alcoholism. But he loved restaurants. So he started at Frank Alberta’s when he was 14—washing dishes and busing tables, then serving and bartending—and decided to make it a career. Glenn couldn’t afford college or culinary school; all but abandoned by his father, and tasked with helping raise his younger brother, Greg, he knew the only way to become a real restaurateur was by outhustling his competition.

Related podcast: Grief, conspiracy theories, and a family’s search for meaning in the two decades since 9/11

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts

And that’s what he did. Studying food like a religion and cultivating an expertise in fine wines—to pair with his effortless charisma—Glenn churned through promotions, running one top-rated establishment after another. In 1997, M. H. Reed, the New York Times restaurant critic, called Glenn “the best front-of-the-house manager in the business.” A year later, he accepted an offer to become the general manager of Windows on the World, the two-floor behemoth that, despite boasting the best views of any restaurant in New York, was bleeding money and earning forgettable reviews. “It was like being asked to play center field for the Yankees,” Glenn told me, “and everyone’s counting on you to turn around the franchise.” By 2000, Windows on the World was the highest-grossing restaurant in America. “Every day was surreal,” he told me. “From the day I walked in until the day I watched it burn.”

Surreal, Glenn notes, is a word overused in describing 9/11. But somehow, it’s the only one that fits. When he first heard that a plane had crashed into the North Tower—while listening to Howard Stern, cruising down the West Side Highway in his Saab convertible on “the most perfect fall morning in New York”—Glenn assumed it was a costly accident. Just the week before, he said, his staffers had leapt from their chairs and run to a window as a small plane roared past the building. Clearing multiple police checkpoints with his World Trade Center security credentials, Glenn parked at the corner of Vesey and West Streets. All he could think of was the 1993 truck bombing and how long it had taken to reopen the restaurant; this plane crash could prove far more damaging to the enterprise. Glenn figured his employees would be frightened. So before exiting the car, he paid special attention to his tie, checking the knot in the rearview mirror. He put on his suit jacket and strode toward the North Tower. He was ready to take control.

And then he reached the lobby.

The exquisite entry doors and windows had been blown out. Alarms and sirens pierced the morning air. Teams of firefighters were descending on the scene, rushing past him and taking up positions inside the foyer. As glass crunched beneath his feet, Glenn climbed gingerly through one of the empty windows and made for the elevators. One of the firemen stopped him, looking incredulously at the gentleman in the fancy suit. Glenn explained that he ran Windows on the World and needed to get upstairs to his employees. The man shook his head. “You need to get out of this building. Right now.”

Glenn backpedaled, puzzled and a bit irritated. Then the first body landed—“like a bomb going off”—on the portico just above him. Moments later, another body, this one hitting the ground nearby. And then another. Bystanders shrieked. The sirens grew louder. The sensory overload was such that Glenn didn’t hear a second airplane smashing into the skyscraper next door. It was only when he stumbled away from the lobby of the North Tower, finally heeding the fireman’s directive, that he noticed the South Tower was burning. He pulled out his cellphone, but there was no signal. Standing next to a couple of cops, he heard one of the police radios: “Watch out for a third plane inbound.”

Panicked, Glenn sprinted over to Battery Park. He wanted a better view of the North Tower—and specifically, of Windows on the World. When he arrived, he encountered two indelible images, scenes that will replay in his mind for the rest of his days. The first was a fireman curled into the fetal position on the ground, sobbing. The second, as he raised his eyes to the top of the North Tower, was white handkerchiefs flying from broken windows. Except they weren’t handkerchiefs. They were white table linens. And Glenn could tell, based on their location, that the people waving them were his employees. Clouds of black smoke cascaded from the building; more and more bodies plummeted toward the earth. In that moment, Glenn thought to himself: They’re all going to die.

“I’m floating through Lower Manhattan like a ghost,” Glenn said. “It was so loud, it was actually quiet.” He was in shock, staggering through the streets in a daze. Clarity arrived in the form of a chance encounter with Bob Van Etten, a top Port Authority official who frequented the Windows bar. “Glenn!” Bob yelled. “Get the fuck out of here! Go home!”

He did what he was told. Retreating to his car, Glenn maneuvered between fire trucks and pulled onto West Street. There were hardly any vehicles on the road, but hundreds of people were running parallel to him, a horde of humanity thundering northward. When he reached Chambers Street, six blocks from the towers, Glenn was stopped by a traffic cop who was trying to make some sense of the mass exodus. A few moments later, after the cop whistled him forward, Glenn heard a collective noise he struggles to describe—gasping, wailing, howling. He looked in his side-view mirror and saw the South Tower crumpling into the streets of New York City. Driving northbound on the Henry Hudson Parkway half an hour later, he listened as Howard Stern announced that the North Tower had fallen too.

“That’s when I shut off the radio,” Glenn said.

To tell Glenn’s story—to convey his perspective on life and death, pain and purpose—is to share an uncomfortable truth: 9/11 was not the worst day of his life.

Twelve years before the towers fell, Glenn was driving home after a long shift waiting tables at Montrachet, a French restaurant in Tribeca. It was almost midnight on October 4, 1989, and he was sweaty and exhausted. All he wanted was a shower and clean sheets. It was Greg’s 21st birthday and Glenn, who was nine years older, felt guilty about not seeing his baby brother to mark the occasion. But Glenn headed home, deciding they would celebrate together the next day.

That night, Greg returned home from a night out with friends, lay down in bed, and lit a cigarette. The apartment caught fire. Greg never woke up. Investigators explained to Glenn that his brother likely died quickly, of smoke asphyxiation, before the flames engulfed his bedroom. But this was of no comfort. Glenn was fixated on the idea that he could have been there; that he should have been there. He descended into what he calls “the darkest place of my life.” In the days following Greg’s death, Glenn could not comprehend how he was supposed to carry on; how he was supposed to live without “my best friend, the kindest, most gorgeous kid you’d ever want to meet.” Glenn is not a religious man. But during the funeral—as my father, a young minister, eulogized Greg and prayed over his soul—Glenn heard these words echoing through his mind: You need to keep going.

“Life takes these crazy twists and turns. And when a terrible thing happens—when a tragedy hits—you can feel like it’s the end of your story,” Glenn told me. “But it’s not. And that’s what hit me when we buried Greg. I needed to keep going, because there’s more to my story. It probably sounds cliché. But I just remember thinking that people needed me. People I didn’t even know yet. And I had to keep going for them.”

When the service ended, Glenn told his wife, Merry Anne, about his epiphany. Their interpretation was the same: They wanted a son. And so, 10 months later, the couple welcomed a baby boy. Taylor Vogt—named for the New York Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor, Greg’s and Glenn’s favorite player—became his father’s shadow. They bonded over everything—books and sports, music and food. Even as a young child, Taylor would wait up late until Glenn came home from his restaurant jobs, and the two would talk and tell stories into the early morning hours. Glenn couldn’t hope to be the same after his brother died; an edge, a quiet and veiled hostility, settled over him, often surfacing without warning. Nevertheless, the joys of fatherhood validated everything Glenn came to believe after Greg’s death—that instead of wallowing in anguish, he could will himself forward with a belief in long arcs and winding roads.

Glenn believes this redemptive cycle—the despair associated with Greg’s death, followed by the delights of bonding with Taylor—prepared him for September 11. Thrust into the public eye after such an unthinkable calamity, Glenn expected to feel outmatched and overwhelmed. Instead, he told me, “I had this weird equilibrium. It was horrible, obviously. I lost so many friends. But nothing could ever take me lower than I was when Greg died. And when you’ve been at your lowest and survived it, you walk away with this ability to help other people get through their low points.”

Glenn thought for a moment. “Had I not gone through Greg’s death, 9/11 probably would have broken me.”

There’s a more fateful way of looking at it.

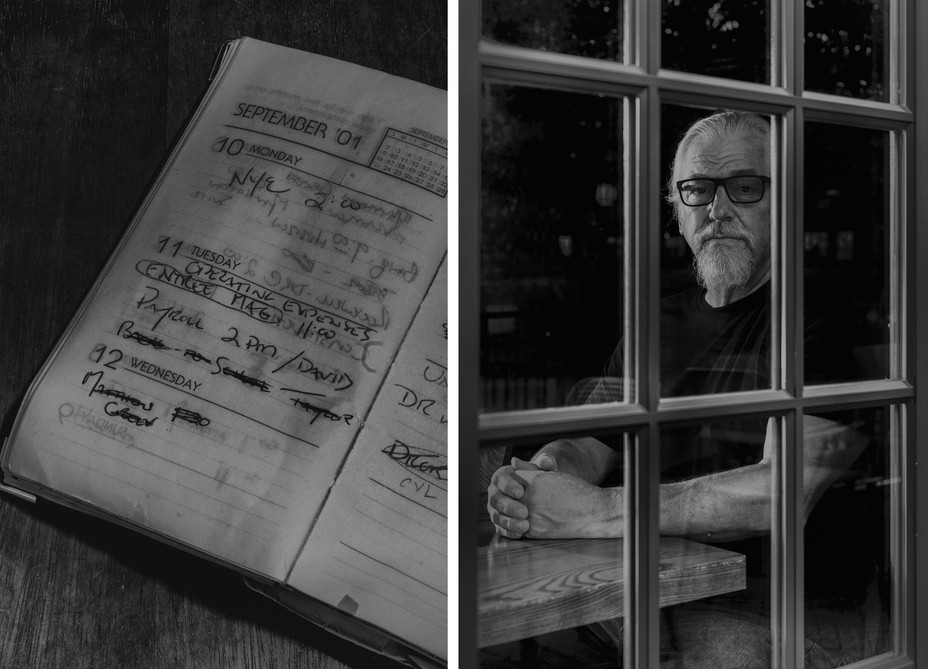

On the morning of September 11, Glenn had a scheduled 9 a.m. meeting with his assistant, Christine Olender, to plan for the restaurant’s New Year’s Eve celebration. Glenn was a stickler for being early; a 9 o’clock meeting meant he belonged in his office by 8:45. That morning, however, Taylor—having stayed up the night before, talking with his dad—was late for school. As Glenn walked out the door of their home in Westchester County, Taylor, a sixth grader, yelled for him to wait. He needed a ride. It was that unplanned 15-minute detour that placed Glenn on the West Side Highway at 8:46 a.m., when the North Tower was hit, rather than inside his office on the 106th floor.

“You can’t make it up,” Taylor told me, sipping a stout inside RiverMarket Bar & Kitchen, the stylish spot Glenn owns in Tarrytown, an hour north of where the towers stood. “My father couldn’t save Greg. My parents had me to replace Greg. And then I wind up saving my father.”

Every name evokes something: a story, a biographical quirk, sometimes even a laugh. As Glenn drifted along the wall, tracing the letters with his fingers, he seemed to have a vignette ready for each person.

HOWARD LEE KANE. (“He actually had Crohn’s disease, so he was never feeling great, but he was just so kind to everyone. So sweet. He was on the phone with his wife when the plane hit.”) VIRGIN LUCY FRANCIS. (“She worked in the ladies’ bathrooms, making sure they were clean, restocking items. Always had a smile … Her son worked here too. But he was off that morning.”) STEPHEN GEORGE ADAMS. (“He came in at eight in the morning, picked up the bar requisitions … If he worked fast, he would have the bars stocked by four in the afternoon. It wasn’t a glamorous job. I doubt we paid him very much. But man, he was so proud of working at Windows.”) ROSHAN RAMESH SINGH and KHAMLADAI KHAMI SINGH. (“Brother and sister. We had a couple of those … When I went to their temple in Queens, their mom came over, grabbed me, made me sit down on a pillow with her, and she just prayed and cried. She lost her only two kids.”)

Glenn talked to me and Taylor uninterrupted for nearly 40 minutes, rattling off obscure factoids about dozens of the departed. He spoke of the undocumented immigrant whose small children asked if Glenn was Jesus when he took them to a church to arrange for social aid. (This, he noted wryly, was long before he grew out his hair.) He grinned while telling me about the big, intimidating, Harley-riding beverage manager who was gay—a fact that stunned colleagues at his funeral. He went into detail about the servers who picked up last-minute shifts that morning and the brand-new parents whose children are now adults. Whenever emotion choked his voice, Glenn was quick to compose himself and carry on.

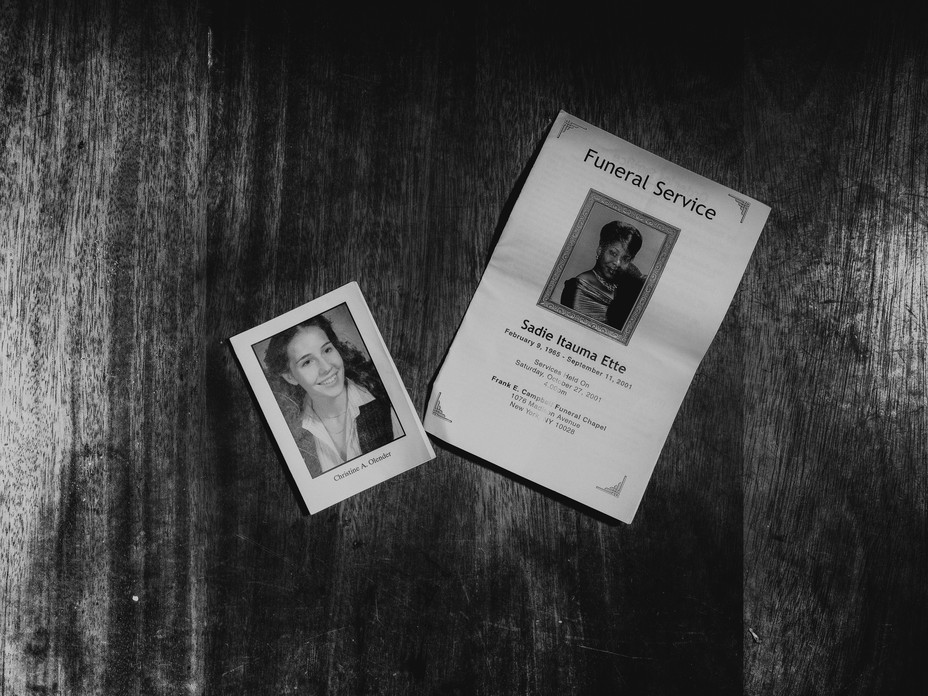

With one exception: CHRISTINE ANNE OLENDER.

Glenn couldn’t manage any words as he leaned over the name. He didn’t need to. If I knew one part of his 9/11 story, it was the part about Christine, his assistant, his dear friend and right hand in running the restaurant. When Glenn pulled up to his home around 11 a.m. on the morning of the attacks, the first thing Merry Anne sobbed—after bolting from the house to embrace him—was “I thought you were dead!” And then, moments later: “Christine kept calling. I told her you’d be there any minute.”

Their living room was bustling. Family friends had picked up Taylor and his younger sibling from school. Neighbors had brought food. It had all the makings of a wake; the only thing missing was a corpse. Bothered by the scene—and by the sights and sounds coming from the television—Glenn escaped to the front porch with Merry Anne. They wept together as she relayed the phone calls from Christine, from the first call, wondering why Glenn’s cellphone wasn’t working, to the final call, telling Merry Anne they were suffocating and asking if she thought it was okay to break a dining-room window. For everything he had just witnessed, Glenn realized, his wife had endured something every bit as traumatic, speaking to a friend for whom a ghastly death was rapidly approaching.

Glenn didn’t sleep that night. He’s not even sure that he lay down. He needed to act. He needed to keep going.

He called the dozens of managers who reported to him and organized a meeting the next morning at Beacon, a sister restaurant in the city, where they could establish a record of the Windows staff. When they gathered, David Emil, a co-owner of both restaurants, stood to deliver remarks but quickly broke down in tears. So did the rest of the room. “These people in the building, they were our friends,” Glenn told me. “People we saw every day. And suddenly, they were gone. There were no remnants. There were no bodies. They were dust. It was so sad. But it was also just overwhelming. We didn’t have the cloud back then; most of our information was on computers that were destroyed. And we’re trying to account for 500 employees. It’s like, where do we even start?”

With Beacon as their operating base, Glenn and his managers launched a round-the-clock effort to identify victims and survivors within the Windows family. They pieced together shift cards and vacation schedules. They aired a special hotline number on every news station in New York and took turns answering phones. Every employee they contacted offered clues about colleagues who hadn’t been located. It took three weeks, but finally, Glenn and his team had a full accounting of their staff. The awful bottom line: 72 Windows on the World employees died in the attacks, plus another seven contractors who worked in security, renovations, and maintenance.

With all the victims identified, Glenn stepped forward to serve as the restaurant’s liaison to the surviving families. He visited spouses and children and siblings and parents, sharing workplace memories of the deceased. He talked with national newscasts and small-town newspapers, offering reflections on the restaurant and its staff. He attended so many funerals—40? 45?—and shook so many hands and hugged so many grieving people in the fall of 2001 that he would occasionally lose track of where he was and to whom he had come to pay respects.

At a certain point, Glenn said, “it became too much.” He had tried to project the sort of grace and empathy people demand from leaders in times of crisis. But he was weary, haggard, desperate for something to interrupt the months-long spiral of grief.

His salvation—at least for a time—was Windows of Hope. The restaurant’s head chef, Michael Lomonaco, had suggested a charity to support the families of their fallen colleagues. When Michael Bloomberg offered to underwrite the operation, Glenn jumped in, helping spearhead a fundraising campaign that eventually generated more than $25 million. The money was dispersed continuously—no questions asked—to 110 families of food-service workers who died in the attacks. (Glenn is most proud that the aid was not exclusively for Windows employees; he recalls bawling on the phone with the wife of a Halal-cart operator, an undocumented immigrant, who had been crushed by falling debris, leaving her widowed and penniless.)

“People in my situation ask, ‘Why me? Why did I survive when so many others died?’” he said, staring into the reflecting pool of the North Tower. “The only time I felt like I had an answer was when I was helping those families.”

Taylor interrupted. “It wasn’t just them, Dad,” he said. “What if your name was on this wall? I wouldn’t be here. There’s no way.”

Pulled out of his sixth-grade class by the school principal on 9/11, Taylor was told that there had been a fire at the World Trade Center—and that his mother needed him at home. “And I’m thinking, right away, My dad is dead. There was no doubt in my mind,” Taylor told me. Ninety minutes later, when Glenn walked in the front door, Taylor went numb. As they embraced, the stoic child uttered words that both father and son still recite to this day: “As long as you’re okay, then I’m okay.”

But Taylor wasn’t okay. He had always been intelligent but high-strung, prone to bouts of fitful behavior. The post-traumatic stress disorder he believes he experienced after 9/11 added a volatile element to his personality. Then, as a teenager, he was diagnosed as manic bipolar.

When it became clear to Glenn and Merry Anne that he needed to be hospitalized, Taylor fought them, cursed them, told them he would never talk to them again if they put him in a psychiatric ward. Merry Anne, who had been emotionally scarred by 9/11, could not bear it. But Glenn could. He visited Taylor every day, at each one of his hospital stops. He brought food. He told stories. He kissed his son’s forehead and promised him that they would keep going—together.

And they did. Taylor, who is now 31, has two master’s degrees and a loving girlfriend, and has been episode-free for the better part of a decade. For all the family folklore of him saving his father on 9/11, Taylor told me, it was his father who saved him in the years that followed.

Our conversation at the memorial underscored how much Glenn had done for others—and how little he had done for himself. Just as in the years following Greg’s death, Glenn committed himself to charging ahead at high speed in the aftermath of 9/11, believing the only antidote to heartache was forward momentum.

The result was a sort of existential divergence. On the surface, Glenn was providing so much help, so much inspiration; one layer beneath, he was suffering a slow-motion breakdown. He did more drinking than eating. He did not sleep. He did not seek help. (After a single session of therapy, he called the shrink a “pompous asshole” and never returned.) All the lights were blinking red, warning Glenn to slow down. But he just kept going.

Glenn bounced between restaurant ventures in Manhattan for some years after 9/11. But it never seemed right. Having played center field for the Yankees, he felt like he was suddenly pinch-hitting in the minor leagues. Underwhelmed by his opportunities—and haunted by the altered skyline of Lower Manhattan—Glenn quit the city’s culinary scene a decade ago. He retreated to Westchester and took on several projects for wealthy benefactors. Finally, in 2013, Glenn opened RiverMarket, achieving a lifelong dream of owning his own restaurant.

He still works a dining room with the best of them, kissing cheeks and pulling up chairs and picking up the tab for regulars or newcomers he takes a liking to. But there are some patrons he doesn’t take a liking to—and he’s not afraid to tell them so. Glenn does not have lukewarm opinions or casual disagreements. He has always been a passionate guy—it’s part of what’s made him so successful—but he used to know how to keep things in perspective. That, he admitted to me, is no longer the case. He seethes over a negative Yelp review. He tells unhappy customers not to return. Recently, after someone left a server a 10 percent tip—“No mask?” the customer wrote on the receipt—Glenn posted an expletive-laden Instagram rant that included an image of the receipt, complete with the person’s name and signature. “Hoping only the worst for you always,” Glenn wrote in the caption.

On Saturday night, after we returned from our visit to Ground Zero, RiverMarket was bustling. Glenn’s regulars didn’t seem to sense that anything was amiss. But I did. His eyes betrayed a deep melancholy; his voice carried an unfamiliar twitchiness. At one point, he came to the bar, where I was sitting, and told me that a couple on the patio had complained to him about not being served proper silverware with their appetizers. “We had to eat oysters with our regular forks,” he whined in a mocking tone. We both rolled our eyes. He let out a long sigh. Then he told me he was thinking about taking an oyster fork to the patio and stabbing it into the man’s forehead.

I knew he was joking. But there was something unsettling in his tone. Glenn has become every bit the old-world Sicilian he grew up despising—a loyal guy, a loving guy, and a guy with a frighteningly short fuse. Earlier this year, when a disgruntled ex-employee flipped him off during a terse exchange at a local bar, Glenn choked the man and nearly bit off one of his fingers during the ensuing brawl. The criminal charges were dropped when Glenn agreed to attend anger-management classes. He said it was the best thing that could have happened to him. “I found some ways to cope. You know—breathing techniques, keeping a dialogue in your head, that kind of stuff,” he told me. “I really did feel less angry for a while.”

On Sunday morning, during a scenic drive through the Hudson Valley, I asked Glenn about the oyster-fork threat. Suddenly, his eyes welled with tears. “Why am I so mad all the time?” he said, shaking his head. “I don’t know. I really don’t know.”

My heart dropped in that moment. Glenn is one of the most generous humans I’ve ever met, and he’s endured more than most people can imagine—a lifelong series of tragedies and near-tragedies that makes you wonder how many times a single man can cheat death. Earlier this year, a freak lightning strike burned down half of his house. Then, the night before I arrived in Tarrytown, flash flooding from Hurricane Ida trapped Glenn in his pickup truck in a gully. As the water rose to his stomach and the cops tossed a rope ladder to his rescue, he wondered if his time was finally up.

“None of that is an excuse,” he told me. “And 9/11 isn’t an excuse. But, you know, yesterday …” He paused. “Yesterday was hard.”

“What,” I asked him, “was the hardest part?”

“There were names that I couldn’t remember,” Glenn said, his voice quivering. “And that makes me feel horrible. It hit me really hard. When we got back to the restaurant, that’s all I could think about. I was responsible for those people, you know? And I couldn’t even remember some of their names.”

We rode in silence for a minute. Then he went on. “The only secret to life that I’ve discovered is that you’ve got to keep going. Right? That’s what I’ve always subscribed to. If you keep going, you find happiness, because people will need you,” Glenn said. “And honestly, as terrible as 9/11 was, I found some happiness afterward because I could help those people. People needed me—”

He stopped and swallowed hard. “It’s been 20 years. They don’t need me anymore. And I can’t even remember some of their names.”

Glenn has frequent dreams that he’s inside the North Tower, inside Windows on the World, on September 11. There are competing versions. In one dream, he is pulling a massive hang glider from his office closet, hitching it to his employees, and flying them to safety. In another, he is caught inside with them, choking on the deadly fumes, hugging them tight and preparing to die the same death as Greg. And then there is a third dream—one with no fire, no plane crash, no attack on New York City. The restaurant is intact. But it’s filled with strange faces; the employees are people he does not recognize, and they are ignoring him. At the beginning of my conversations with Glenn, this seemed quite obviously to be the least distressing of his visions. By the end of our time together, I had come to realize that it was his worst nightmare.

“I had a purpose after Greg died. I had a purpose after 9/11. And now—I just don’t know,” Glenn told me, gripping the wheel so tightly that I could see the blood draining from his knuckles. “I hope there’s something else for me, something else that’s fulfilling, before it’s my turn to leave. I always felt like I needed to be strong for others who can’t be strong for themselves. But I don’t feel so strong anymore.”

Once the clean-cut Manhattan backslapper with a five-figure wardrobe and a Rolodex full of New York City’s elite, Glenn would go unrecognized in Tribeca these days. His daily uniform is a black T-shirt with blue jeans. He sports thick black glasses, a scruffy goatee, and hair down to his shoulders. It’s usually in a ponytail, but as we talked in the car, thinning wisps of white stuck to the corners of his eyes, damp with tears.

I reminded Glenn that he had welcomed my visit—and my probing of his life—to help him find some peace. So I asked him the obvious question: In order to keep going, isn’t it necessary to leave certain things behind?

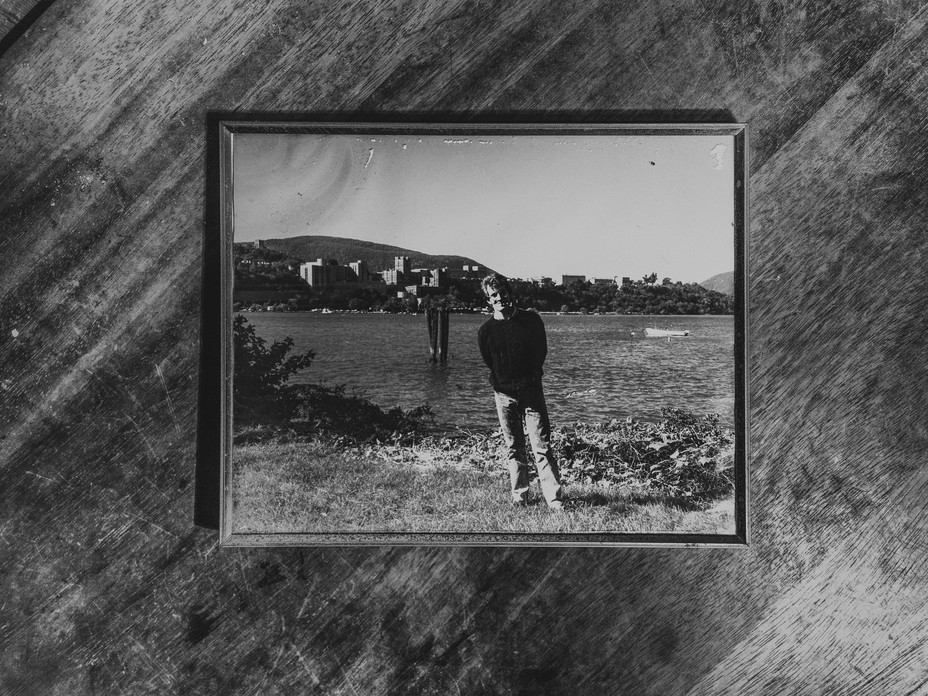

“Greg has been dead for 32 years,” Glenn replied. “I still think about him every day. I still pull out this tiny box of his things and look at these old photographs. I still cry. I want that pain right here”—he tapped on his chest—“so I don’t forget him.”

For the longest time, Glenn told me, he took the same approach to 9/11. He would reread obituaries every anniversary; he would watch documentaries and look up old news clips. He would try to hold his former employees—and the pain of their loss—as close as possible, for fear of forgetting. But as the years slipped away, his dedication waned. New priorities emerged. And sure enough, he began to forget.

Glenn said he would spend this September 11 feeling guilty about that. But I could already tell, by the time he dropped me off at the airport, that his burden was lighter. He asked if we could keep talking about all of this, after my story was published, and I promised that we would. I’m hoping he feels a little less guilty next September, and even less guilty the September after that. Because moving forward isn’t the same as moving on.

This article originally misidentified the Windows on the World co-owner who spoke at the meeting at Beacon restaurant. It also said RiverMarket opened in 2003; in fact, it opened in 2013.