The Perils of ‘With Us or Against Us’

A healthy deliberative process needs to make room for dissent.

When I was 21, the United States experienced a national trauma: the planes crashing into the World Trade Center, the nearly 3,000 people killed in that day’s terrorist attacks, the ruins left smoldering for months at Ground Zero, and the unnerving knowledge that sooner or later, al-Qaeda would almost certainly strike again. Thoughtful deliberation is never so difficult as in such moments. Like tens of millions of other Americans, I felt fear, anger, anxiety, flashes of moral righteousness, and a desire to fight and vanquish evil as I thought about what had just happened and how America ought to respond. With hindsight, though, I can see that thoughtful deliberation is never so vital as in the aftermath of national traumas. The country would have been well served then by a better debate with less aversion to dispassion and dissent and fewer appeals to moral clarity at the expense of analytic rigor.

Recall the national determination to punish not only Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda, who carried out the thousands of murders, but also the regime in Afghanistan, which harbored the terrorist organization; the dictator of Iraq, who had nothing to do with the attacks; and more abstractly, the tactic of terrorism, the ideology of Islamofascism, violent extremism in general, and terror itself. Eventually, President George W. Bush asserted that the ultimate goal was “ending tyranny in our world.” The utopian zeal he stoked portended avoidable catastrophes. But anyone who raised prudential concerns at the time was suspected of being disloyal or insensitive, or of lacking moral clarity.

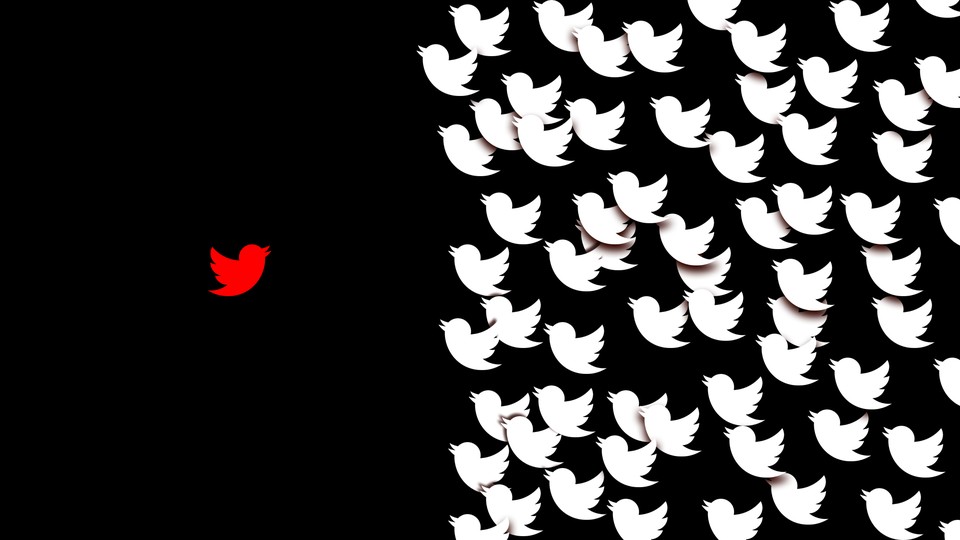

No two eras are exactly the same. No analogue to Bush himself exists in our present moment of national trauma, no mistake as catastrophic as the Iraq War is yet apparent on the horizon, and the advent of social media has transformed the way that social and cultural orthodoxies are enforced. But the problem of egregious police killings has been thrust back into the national spotlight by video of the white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man––and the nation now faces complicated, consequential questions about who or what to fight. Americans are protesting not only killer cops, the colleagues who abet them, and the unions that protect them, but also policing itself, Confederate statuary, “white fragility,” neo-colonialism, microaggressions, systemic racism, neoliberalism, and capitalism.

As a hearteningly broad coalition embraces policing reforms, a distinct, separable struggle is unfolding in the realm of ideas: a many-front crusade aimed at vanquishing white supremacy, hazily defined.

That crusade is as vulnerable to mistakes and excesses as any other struggle against abstract evils. Some of the most zealous crusaders are demanding affirmations of solidarity and punishing mild dissent. Institutions are imposing draconian punishments for minor transgressions. Individuals are scapegoated for structural ills. There are efforts to get people fired, including even some who share the desire for racial justice. There are countless differences between the Bush and Donald Trump eras, including the way our politics is shaped by Trump’s incompetent brand of authoritarian cruelty. But in the stifling, anti-intellectual cultural climate of 2020, where solidarity is preferred to dissent, I hear echoes of a familiar Manichaean logic: Choose a side. You are either an anti-racist or an ally of white supremacy. Are you with us or against us?

The range of institutions affected by recent excesses is remarkable. Here I can note only a small sample of what’s been reported. The University of Chicago economist Harald Uhlig tweeted that Black Lives Matter “torpedoed itself” by supporting calls to defund the police. “Time for sensible adults to enter back into the room and have serious, earnest, respectful conversations about it all,” he wrote. “We need more police, we need to pay them more, we need to train them better.” In response, other academics organized a campaign to remove him from the editorship of a scholarly journal; and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, a quasi-governmental institution, cut ties with him, asserting that his views are incompatible with its “commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion.” Yet the beliefs that defunding the police is a bad idea, and that protesters who advocate for it will lose political support, are common. Many at the Fed surely hold them. All political litmus tests in public institutions are fraught. That litmus test is farcical.

At UCLA, Gordon Klein, a lecturer who has taught at the institution since 1981, dismissively declined an emailed request to alter the requirements of his final exam for Black students during the George Floyd protests. “Are there any students that may be of mixed parentage, such as half black-half Asian?” he wrote. “What do you suggest I do with respect to them? A full concession or just half?” He concluded the email, “One last thing strikes me: Remember that MLK famously said that people should not be evaluated based on the ‘color of their skin.’ Do you think that your request would run afoul of MLK’s admonition?”

Denying the student’s request was within his discretion, as UCLA’s Academic Senate’s Committee on Academic Freedom affirmed. Nevertheless, a petition calling for his dismissal accrued 21,000 signatures, and he was suspended pending an investigation. “This investigation is almost certainly based on the tone or viewpoint of his email, which was—however brusque—protected expression on a matter of profound public interest,” the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education argued. “Klein must be immediately reinstated, and UCLA’s leaders must make clear that their commitment to academic freedom is stronger than an online mob.”

In Vermont, a public-school principal posted her thoughts about Black Lives Matter on Facebook:

I firmly believe that Black Lives Matter, but I DO NOT agree with the coercive measures taken to get to this point across... While I want to get behind BLM, I do not think people should be made to feel they have to choose black race over human race. While I understand the urgency to feel compelled to advocate for black lives, what about our fellow law enforcement? What about all others who advocate for and demand equity for all?

Her school board quickly announced that despite the principal’s “meaningful and positive impact,” her “glaring miscomprehension” of Black Lives Matter would damage the school and its students if she remained in charge. They removed her for speech that is clearly protected by the First Amendment, engaging in viewpoint discrimination. That is an unlawful violation of her civil rights.

A respected data scientist, David Shor, tweeted a link to Princeton Professor Omar Wasow’s recently published academic paper concluding that violent protests diminish the electoral prospects of the Democratic coalition. As a result, he was banned from a listserv of left-of-center data analysts and appears to have been fired from his job at Civis Analytics. (Emerson Collective, the majority owner of The Atlantic, is a minority investor in Civis Analytics.) “For those of you who don’t realize what makes the tweet problematic,” one member of the listserv wrote, “try not to overanalyze the statistical validity of the research paper and think about the broader impact it will have if people perceive it to be true.” That standard demands that people self-censor the truth.

A group of policing-reform advocates identified eight use-of-force policies that are statistically associated with fewer police killings. Then they successfully lobbied dozens of cities to adopt their “8 Can’t Wait” measures, such as banning chokeholds, mandating de-escalation, and requiring cops to intervene to stop excessive force. In a sign of the times, their website now leads with a mea culpa. “Even with the best of intentions, the #8CANTWAIT campaign unintentionally detracted from efforts of fellow organizers invested in paradigmatic shifts that are newly possible,” they wrote. “For this we apologize wholeheartedly, and without reservation.”

Because even insufficient radicalism from allies draws ire, many may feel tempted to keep quiet and observe. But “silence is violence,” some insist. That phrase is chanted on the streets, and its logic is being applied to individuals and institutions. In The New York Times, the author Chad Sanders urged shunning of the silent, advising his white friends to text their relatives and loved ones “telling them you will not be visiting them or answering phone calls until they take significant action in supporting black lives either through protest or financial contributions.” Those are cult tactics.

The theater producer Marie Crisco created and circulated a Google Doc titled “Theaters Not Speaking Out” naming and shaming more than 400 performing-arts venues that “have not made a statement against injustices toward black people.” The Los Angeles Times reported that many theaters then posted messages of solidarity with Black Lives Matter. Crisco told the newspaper that the words seemed to come from a place of shame and “felt slapped together and hollow.”

How could they not? Before this month, no one expected theaters to release statements on worldly injustices or for theater staffers to be skilled at drafting them with the right tone and substance. Yet many institutions are treated as if a failure to quickly publish something that conforms absolutely to highly contested interpretations of anti-racism renders them deserving of opprobrium.

A Denver bookstore, The Tattered Cover, felt compelled earlier this month to explain why it had not released a statement on protests in its city. “We want to make a statement of support and take a moment to explain why we’ve been quiet,” the book store’s owners declared. “We agree with, embrace, and believe that black lives matter. We reject the statement ‘All Lives Matter’ as an either valid or helpful response ... We stand in solidarity with our black friends and neighbors, and grieve the senseless and brutal loss of life; not just of George Floyd and other recent victims, but of all lives lost from centuries of oppression and abuse. We believe there must be systemic change.”

So why had it kept quiet? The bookstore explained that it had maintained a “nearly 50-year policy of not engaging in public debate,” premised on a belief that even proclaiming “simple and unalterable truths” would be anathema to a mission it holds dear: “to provide a place where access to ideas, and the free exchange of ideas, can happen in an uninhibited way.” As they saw it, “If Tattered Cover puts its name and weight either behind, or in opposition to, one idea, members of our community will have an expectation that we must do the same for all ideas. Engaging in public debate is not, we believe, how Tattered Cover has been and can be of greatest value to our community.” The owners closed by pledging to feature more titles by Black authors, to schedule more events with Black authors, and to continue to hire and promote employees from diverse backgrounds.

Their statement of supposed neutrality affirmed everything most businesses say when supporting Black Lives Matter. But because it did not treat solidarity as preeminent, it was deemed too problematic to abide. “I’ve just told my publicist to cancel my 6/23 event in conjunction with Tattered Cover,” the author Carmen Maria Machado announced. “Unlike the owners, I know that choosing neutrality in matters of oppression only reinforces structural violence.”

Soon, the owners released a second statement apologizing for the first one. “We are horrified at having violated your trust. We deserve your outrage and disappointment,” it began. “Tattered Cover will no longer stand by while human rights are being violated. To be silent is to be complicit, to be neutral in the face of injustice is an act of injustice itself.” In fact, statements of solidarity and self-flagellating apologies for wrongthink don’t advance social or racial justice any more than displaying and exalting the American flag after 9/11 made the U.S. safer from al-Qaeda. For now, the bookstore has failed to release statements condemning America’s campaign of drone strikes, War on Terror detainees still held in indefinite detention, or the epidemic of rape and sexual abuse in juvenile-detention facilities. Is the bookstore complicit in all of those evils?

Unanimity is neither possible nor necessary to fight racism. On the contrary, attempts to secure unanimity can undermine the fight: They needlessly divide anti-racists and weaken everyone’s ability to grasp reality. When demands for consensus are intense, people may clam up or falsify their own beliefs. When truth-seeking can get you fired, some people stop seeking the truth. Granted, unfettered liberal deliberation is not sufficient to solve problems as difficult as reining in police abuses or ending systemic racism. But it is necessary no matter how just or urgent the cause. America can achieve more good and harm fewer people with more frank debate, less aversion to dissent, and fewer appeals to moral clarity at the expense of analytic rigor.

Street protests don’t need to stop. Pressure for reforms and accountability should continue. But demands for conformity may permanently damage institutions that can enrich society with their diverse missions and priorities. Short-circuiting debate may deprive Americans of insights on what sorts of protests are effective; how to reform police departments without a spike in murders or other violent crime; how to distinguish between and combat ideological racism versus authoritarianism; how to educate children more equitably; how to determine the potential costs and benefits of race-based reparations; how to determine the relationship among journalistic institutions, their missions, and their readers; how to assess the protections that capitalism can afford to ethnic and religious minorities; and much more.

Absolutely, Black lives matter, which is part of why everyone should encourage constructive dissent, even when it seems frustratingly out of touch with the trauma and emotion of the moment. Identifying changes that will achieve equality is hard. Avoiding unintended consequences is harder. Without a healthy deliberative process, avoidable catastrophes are more likely.