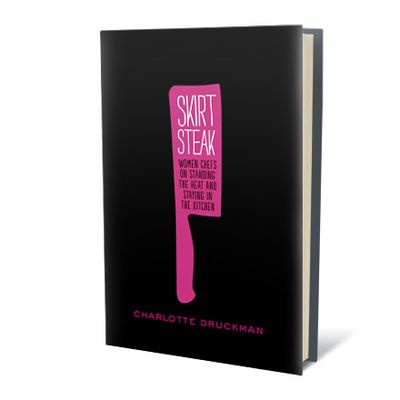

Earlier this week, Chronicle Books released Charlotte Druckman’s Skirt Steak: Women Chefs on Standing the Heat and Staying in the Kitchen. As you can glean from the title, the book deals with the hardships women face in the professional food world, as told by chefs like Alice Waters and Christina Tosi. Straight ahead is an excerpt from the book’s third chapter, “In the Man Cave.”

Sarah Schafer was the first female sous chef in Danny Meyer’s empire (the Union Square Hospitality Group), which includes heavies like Eleven Madison Park and Gramercy Tavern, where she worked. Within those mostly-male temples, any success she had was met with hostility and, often, cruelty. When she arrived at Gramercy after three months of trailing in different restaurants around town, Schafer was shocked when Tom Colicchio (1998—back in the day, people) offered her a job as a line cook. This was unheard of; incoming young bucks would start out as “tavern cooks” and focus on food for the restaurant’s more casual front room, the Tavern. Eventually, they’d be promoted to serve the main dining room as line cooks. Not Schafer. She was put on the appetizer station.

A man who applied for a job right after she did was granted, like everyone else, the “tavern cook” title and directed all of his anger at Schafer, whom, he believed, stole his place (because how could she have been chosen on merit, right?). On comes the sabotage. He managed to turn off her stove and burned her with fish stock. And when one is assaulted with a pot of boiling liquid, what does one do? Schafer was advised not to go to the hospital, but, instead, to get a bucket of ice and spend the rest of that evening’s service with her injured foot in the bucket. Did she? Sure. And then, once the kitchen had shut down for the night, she was able to go to the hospital. What other choice did she have?

“I guess it’s a horrible thing to say, but I didn’t want to seem like a woman in their eyes,” she admits. “I just wanted to be there to cook and be respected for that.”

Six months later, her grin-and-bear-it pain tolerance landed her that sous position. But even at that level, the “different” treatment prevailed. At the meetings she attended, she would be asked to leave at moments, she presumes, when the agenda turned to “bawdy sex stuff.” She stuck it out and eventually left for San Francisco, where she ran a number of restaurants, including those of Doug Washington and brothers Steven and Mitchell Rosenthal. When that team stormed Portland, Oregon, to launch Irving Street Kitchen in 2010, Schafer moved north to lead the charge.

After getting burned, it would be easy to resort to retaliation, but, according to Traci Des Jardins, the way to endure and rise is not to look back at the people behind you in the race; don’t get bogged down in the meanness. Keep on running, and understand that you might need to be selfish—worrying about someone else’s setback is not productive. She put this as candidly as anyone could: “Do you have to fight your way to the top? Is it a battle? Is it cutthroat? Yeah, it’s like, people ask, ‘Do you have to be cutthroat?’ In a way you do. You don’t have to sabotage other people, but you have to willing to step over the bodies … People will usually self-destruct. But, you know, in the French environment, in the kitchens that I grew up in, it was dog-eat-dog; if you weren’t rising to the top, you were going to the bottom.”

This culinary sport is rough stuff. That’s a fact. Amanda Cohen contends that the competition is steeper for the girls who want to participate. It’s as though the entire male gender is seeded while the ladies, all unranked, have to duke it out to score a single entry slot in the tourney bracket. “When you go in as a woman, your competition is the other woman working in that kitchen.” Chills the blood, that. “And I think if you’re a man, you walk into a kitchen and you’re like, ‘I’m going to do the best job here. Who’s the best chef at this restaurant? I’m going to compete with [him].’ If you’re a woman … there’s only room for one, if you’re lucky, two [of you].’ In other words, in an industry in which support is essential, women are actually being encouraged to undercut each other. Cohen, of course, gets how detrimental and ridiculous this mentality is; still, she can’t completely free herself from that destructive conditioning. “That might not be true. But that’s how you feel. ‘Okay, it doesn’t even matter who the best cook is here; I’m going to be compared to this woman. And she might be horrible and she might be great, but that’s my competition.’ ”