Is the Bar Too Low for Special Education?

The Supreme Court is poised to decide the quality of instruction public schools must provide students with disabilities—a question that could get even thornier under the Trump administration.

In fourth grade, Drew’s behavioral problems in school grew worse. Gripped by extreme fears of flies, spills, and public restrooms, Drew began banging his head, removing his clothing, running out of the school building, and urinating on the floor. These behaviors, which stemmed from autism and ADHD, meant that Drew was regularly removed from the classroom in his suburban school outside of Denver and only made marginal academic improvement, according to court documents.

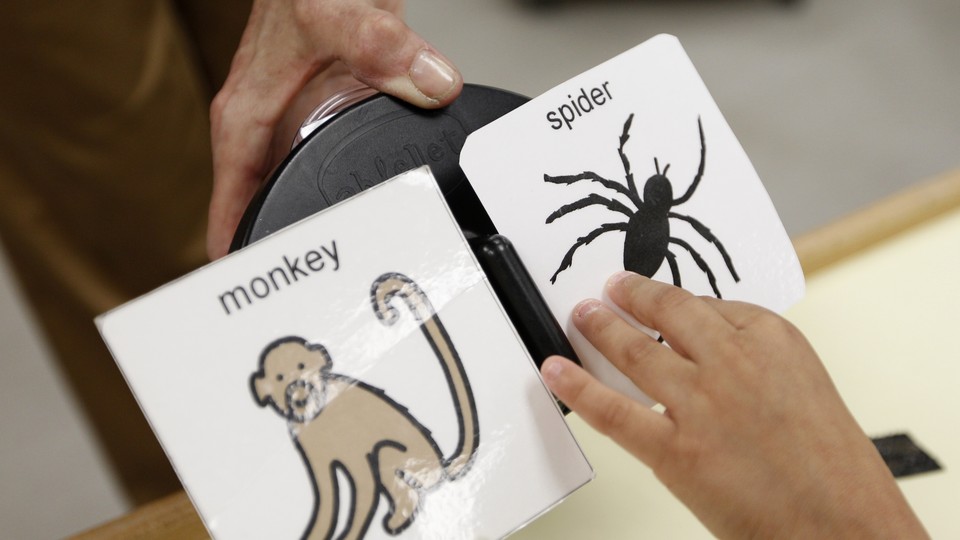

Alarmed by their son’s increasingly difficult behaviors, his parents placed him in a private school that specializes in autistic children like Drew. The new school controlled Drew’s behaviors using ABA therapy—a standard, but intensive, treatment for autistic children with behavioral problems that was not offered at his public school. Now age 17, Drew has made “significant” progress academically and socially at his new school.

In 2012, Drew’s parents filed a complaint with the Colorado Department of Education to recover the cost of tuition at this school, which is now about $70,000 per year. The lower courts ruled on behalf of the school district on the grounds that the intent of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is to ensure handicapped kids have access to public education—not to guarantee any particular level of education once inside. But the parents appealed, and the case—Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District—is now under review of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The case revolves around a central question: Must schools provide a meaningful education in which the child shows significant progress and is substantially equal to typical children, or can they provide an education that results in just some improvement? If the Supreme Court rules on behalf of Drew and his family, agreeing that special education shall be held to a higher standard, then it will open up a thornier question: Who should pay for it? And that question could be even harder to navigate under President Donald Trump, whose pick for education secretary, Betsy DeVos, during her Senate confirmation hearing last week said she believes that the rights of special-education students should be decided by the states.

Drew’s case marks the next chapter in the evolution of special education in the United States. In 1975, Congress found that children with disabilities were “either totally excluded from schools or sitting idly in regular classrooms awaiting the time when they were old enough to drop out.” That year, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act—which would, in 1990, become IDEA—and provided those children the right to to a “free, appropriate public education,” as well a customized process to achieve certain goals, called an Individual Education Plan (IEP).* For the 2013-14 school year, 6.5 million students—or 13 percent of the public-school population—received an IEP.

This case could expand special-education services even more. But it comes at a time that the federal government is showing signs that it wants to back away from this responsibility—even though IDEA wouldn’t allow for that to happen. At last week’s Senate confirmation hearing, DeVos admitted she was confused about the federal special-education law after indicating that she thought decisions for these children should be best left to the states. “After our meeting and her hearing, I have little confidence that she will fight for more special-education resources for public schools and give every student a fair shot at success,” Democratic Senator Jon Tester, of Montana, told Politico. DeVos’s statements have disturbed parents and advocates for children with disabilities.

Regardless of how, if at all, the education secretary-nominee alters the special-education landscape, Drew and his parents have broad backing from important players in the education-policy world. The National Education Association, 118 members of Congress, and Autism Speaks are among those who’ve expressed their support in favor of Drew’s parents. Gary Mayerson, a civil-rights lawyer in New York City and a board member of Autism Speaks, explained that this case will set a common standard for special education across the country.

Many states, like Massachusetts and New Jersey, meet Education Department requirements for IDEA, suggesting they provide a quality education for their special-needs students. But “this case will simply force those states that have a ‘let’s shoot for the gutter’ standard to improve quality,” Mayerson said. “Schools that have the attitude of ‘we’ll let them be in our schools and pay for a teacher to watch them like a babysitting service’ will have to improve.” These substandard states, Mayerson argued, have “balanced their budgets on the backs of special-ed kids for years.” They’ve spent money on sports programs, for example, and other amenities while often ignoring the special-needs population.

Access to public schools is not enough for children with disabilities, Mayerson contended—they need evidence-based programs and high-quality teachers, particularly because such opportunities can reduce the cost of supporting these individuals as adults. In addition, a new uniform standard would end the “refugee crisis” of parents relocating to states with better special-education services, he said.

But a number of education groups maintain that, despite decreasing state and federal support, the public-school system is serving this population well. The Council of the Great City Schools, the School Superintendents Association (AASA), and the National School Boards Association supported the Douglas County School District in this case. Sasha Pudelski, a lobbyist for the AASA, denied the need to increase the standards for special education, reasoning that “the current system is working. Educators are aiming high. They are already doing plenty.”

Citing the increased rates of inclusion of special-education kids in typical classrooms, as well as increasing graduation rates and decreasing dropout rates among such children, she said that educators “are devoting their lives to improving the lives of kids with disabilities”—even though they don’t always have all the best resources or know the best methods.” And when things aren’t working well, she added, the courts have stepped in appropriately.

A higher standard of special education, Pudelski said, would only create chaos and increase litigation costs, diverting money from students to lawyers; school districts already spend $90 million a year on conflict resolution—most of which goes to special-education cases. The courts would be forced to evaluate educational quality, determine if kids are receiving equal services, and monitor student progress—decisions, she said, that are better left up to educators. Wealthy parents with the resources to hire lawyers are the ones who would benefit most.

Moreover, according to Pudelski, a higher standard would weigh down on an “underfunded, overburdened system.” She said expenses for special education are already encroaching on general-education budgets, estimating the costs at roughly a quarter of those funds—though few states require districts to provide concrete data on these expenditures. Other populations in schools, including ESL students and students in poverty, also have high needs, she added, but don’t have the same protections as students with disabilities. “How will they fare if there is a heightened standards? We have to examine how all kids are being served.”

All this is happening in the context of decreasing funds for special education and education in general. The federal government never provided the 40 percent of special-education funding that it promised when it passed IDEA; right now, it’s only paying 16 percent of special-education costs.

Meanwhile, school budgets keep getting tighter. Thirty-five states decreased per-pupil funding between 2008 and 2014. “School districts are in a world of pain. If we raise the standards of special education, it will mean less money for the general population. Superintendents have to create a budget that benefits all kids. Funding for special-ed kids comes on the back of typical kids.” And there is little indication that funding for public schools or for special education in particular will increase with DeVos at the helm of the Department of Education. “If we want to see better results for special-ed kids, better outcomes, better IEPs, greater adherence to the law,” Pudelski said, “we need the dollars.”

Over the years, as a parent of a student with high-functioning autism who has been educated in three different public school districts, I have seen wide disparities in the quality of special-education programs. Sometimes my son has been offered a well-written IEP with rigorous, measurable goals and high expectations, staff with adequate training and support, and a clean classroom with windows; other times he has not. Keeping him in an excellent program has required an enormous amount of time and effort.

The quality of education has a huge impact on kids like my son. For children with more severe disabilities, simply being able to control troubling behaviors and learning a few words of speech improves their quality of life enormously. Clearly, Drew, the subject of this court case, benefitted enormously from his private school. A good education might give a child a chance at a future with, say, an assisted job at a supermarket and residence in a group home, rather than life in a depressing and expensive institution.

It’s clear that not all states are appropriately serving their students with disabilities. As reported by the Houston Chronicle, the Texas Education Agency put a cap on the number of students who would receive special education services in 2004, thus denying help to tens of thousands of children, even those with Down syndrome. Some families relocated to other states to get help for their children.

At the same time, it’s undeniable that special-education programs are costly and provide few tangible benefits for school districts. School districts are rewarded for giving high-achieving kids, like my oldest son, a variety of AP and honors classes, summer SAT prep class, and a varsity track coach that gets the team into the state championships. Good students raise test scores, increase the ranking of the school, and keep property values high. Special-education students are red marks on the ledger.

If the courts do find that public schools are responsible for providing students with a quality special education, the next step is figuring out a funding model that’s fair. Both sides of this debate maintained that the federal government must increase its funding of special education to at least meet the 40 percent promised to the states by IDEA. Without added dollars, the politics of special education—which is already ugly at the local level—is slated to become even more fraught in the coming years.

* This article has been updated to clarify that the law known today as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act is the revised version of the 1975 All Handicapped Children Act.