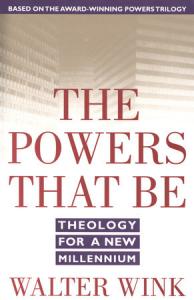

Walter Wink, a Methodist theologian and Bible scholar, has helped modern minds appreciate the New Testament’s language about spiritual reality. Most often for this side of reality we use the word “angels.” It sounds like beings separate from the physical world, interacting with that world occasionally but not by their very nature. In the New Testament, however, the spiritual and the material are close together. Wink sums up the New Testament’s various words for this angelic reality with the phrase: the powers that be.

Walter Wink has been an active campaigner against violence and injustice that the earthly powers that be perpetrate. He has visited South Africa, East Germany, Central America, and Chile in support of nonviolent resistance to oppression. Wink wrote about how Christians can use nonviolent resistance to defeat apartheid. He served on the national steering committee of Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam. With his wife June he has given workshops around the country and the world on Jesus and nonviolence. For Walter Wink non-violent activism and Bible scholarship flow into and support each other.

Until I learned about Wink’s ideas, I saw little point in angels. I could not see how belief in their existence—any more than belief in ghosts—would make a difference. How could they help me with the practical problems of living. But in those practical problems I run up against something bigger than what I can describe with materialistic categories. Walter Wink helped me see that. He also showed me how the New Testament’s language lights up, even for this twenty-first century, a way into that bigger reality.

Naming the powers

The New Testament has many names for angels, or specifications of the genus angels. They are powers, thrones, dominions, authorities, principalities and more. Power seems to be a common thread. In Naming the Powers (pages 65ff), Wink describes some of these that Paul names in Colossians 1:16):

- Thrones – power as located in a symbolic place that outlasts incumbents

- Dominions – the regions over which thrones hold sway, a sphere of influence

- Rulers – not the individuals as such but the “persons-in-office”

- Authorities (or powers) – legitimations and sanctions by which rulers maintain their rule

A sociologist would have a hard time coming up with a more complete, concise list of the political conditions under which we live.

Most of the time, Walter Wink says, that is the way the New Testament means these words—power as people exercise it on earth. It’s a pervasive theme for the Christian Scriptures. But for the world in which the early Christians lived, there was a close connection between earthly and heavenly realms. What happened in one was reflected in the other and vice versa. The same words apply to both and, depending on context, the reference and emphasis could be with one or the other or both.

Here is the whole passage from Colossians (1:16-20) in which Paul names these realities and twice locates them both in heaven and on earth:

He [Christ] is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers; all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have first place in everything. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

Changing the metaphor

Spiritual, or heavenly, reality was an important factor for the New Testament world. If it’s worth our attention today, then where does that reality lie? Metaphorically (usually not literally) Christians have thought of angels as somewhere above. They enter our world, cause some mischief or offer some assistance, and then depart. That’s the picture of two worlds that I noted and rejected in the previous post in this series. Walter Wink brings the two worlds together by a different spatial metaphor. Not above or beyond, but within is where the spiritual reality lies. Wink likens it to the spirit of a team or school or country. It’s a power bringing people together and facilitating feelings, thoughts, and actions – for good and bad – that wouldn’t occur to an isolated individual.

I think Wink means this “within” as another metaphor, but it’s hard not to imagine it literally as a kind of soul. Maybe God zaps it into an organization as humans establish its’ “outer” reality. Here Wink’s idea doesn’t satisfy me, and it may be because of his nearly constant concern with angels of human institutions. He provides hints about angels of nature and the physical world, but not much more than that. In my next post I hope to make good on that lack and bring angelology a little closer to tradition . I also hope not to lose Wink’s insights into principalities and powers.

Catholic theologian Karl Rahner moves in a direction similar to Wink’s, rejecting the idea of a separate world for angels but without trying to nail them down with a metaphor like Wink’s “within.” He says angels

… can be regarded as incorporeal … yet as ‘principalities and powers’ essentially belong[ing] to the world, i.e., the totality of the evolutionary spiritual and material creation. (Quoted from George J. Marshall, Angels … Bibliography, p. 327)

Rahner thinks it best not to think of “such large-scale configurations in nature and history” as resulting directly from God because they are often “antagonistic.” They point, rather, to “antagonistic cosmic ‘principalities and powers.”

Saving angels

Walter Wink proposes an idea that is new to me and, I think worth considering. He says angels, these principalities and powers, are fallen creatures awaiting salvation, like us. Both the New Testament and Wink concern themselves more with fallen and, hence, evil (for Rahner “antagonistic”) powers than good ones. We should resist them but not worry too much about them.

For I am convinced [Paul says] that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:38-39)

These are good creations. God made them in Christ. But we will judge them. (1 Corinthians 6:3) We (that is, the Church) can teach them.

… through the Church the wisdom of God in its rich variety might now be made known to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places. (Ephesians 3:10)

They are among the creatures to be saved, “reconciled,” as Paul says, through “the blood of the cross.” Salvation isn’t just for individuals. The book of Revelation sees nations as among those that God will save. The leaves of the trees on either side of the river of life “are for the healing of the nations.” (Revelation 22:2)

The good and the bad

We couldn’t live without these powers. In their earthly embodiment, as communities, institutions, customs, etc., they are what make existence possible. Contrary to a lot of political thinking in America, we are members of communities before we are individuals.

It would be hard to live without the roles or patterned behaviors that our institutions provide, like the roles of parent and child in the family. We can be creative with these roles. I was the chief diaper changer in my family in the 1980’s and enjoying those moments of closeness. It seemed to me that I was stretching the role of fatherhood as it existed at that time. We can also rebel against established norms. Whether creating or rebelling, we’re always operating from within a context larger than us.

This is a context of realities embodied in but larger than particular instances. They are spiritual realities, realities with power for good, but also power for evil. How do these “angels” turn away from good toward evil?

Idolatry, the primordial sin, but whose idolatry?

It seems unlikely to me that this story of the rebellion and fall of the angel Lucifer and his ouster from heaven by Michael could be factually correct. Can we even speak of facts before the creation of the world? If it’s a true story, it’s true in the way myths are true. Lucifer’s sin was idolatry. Idolatry is what turns the powers—the systems, institutions, ideologies, etc.—from good to evil.

Wink says the spirituality of an institution may be, “at any given moment, idolatrous.” (Naming the Powers, 135) It seems to me that that doesn’t happen unless people are the idolators. But an institution does tempt us to idolize them. We often fall for it. We serve a limited good as if it were an absolute good. What was a gentle power for good becomes demonic. We could direct them toward a greater good, but we let them become tyrannical powers for evil. There are many ways this can happen:

- In politics, love of country, a good thing, can become an idol when I say, “My country right or wrong.”

- Private property can become the idol of economics when I say, “I deserve what is mine and no one can tell me what to do with it” or when justice is only “to each his own,” supported by “law and order,” i.e., whatever preserves the current distribution of valuables.

- The theory of evolution can become the Third Reich’s scientific idolatry of the “superior race” and eugenics. The pursuit of knowledge can also become an idol, justifying cruel experiments on animals.

- In families, roles that ought to be flexible, allowing for give and take, can become frozen patterns of behavior. That’s also an idol.

- We worship social cohesiveness when we segregate ourselves, reject alternative lifestyles, and demonize immigrants.

- People might worship a religion or a religious institution instead of God. That leads to persecution of “heretics,” forced and manipulative conversions, and making religious freedom into a right to impose religion on others.

Angels become devils

In every one of these cases a relative good is mistaken for an absolute good. People can believe they are serving God or the greater good of humanity when they are actually serving an idol. Worship an institution or ideology, and the angel becomes a devil. The overarching context of patterns, structures, systems, institutions, ideologies, ways of thinking, and roles in society—this good world of ready-made meanings in which we live, making us what we are—becomes demonic. These powers keep on making us what we have thus become.

The next post looks at some good angels of the non-human world. They also can become demonic.

Image credit: Penguin Random House via Google Images