Search this site

After Her Father’s Death, a Photographer Explores Grief

“My dad was a good man with a substance problem,” the Canadian photographer Jackie Dives tells me. “He was unique. He was a cat lover, a mechanic, a carpenter, a goof, a friend, a caretaker, and also a drug user.”

When she was a child, Dives’s father taught her how to make things using her hands, from a garden to a go-cart. “My dad dug up a patch of grass behind his apartment building and we dropped pumpkin seeds in a row and pressed rhubarb into the earth,” she remembers.

“He taught me about composting. We raked leaves that became dirt over the winter. He climbed a tall rickety ladder to reach the cherries at the top of a neighborhood tree and we baked a cherry pie from scratch.

“I was always welcome in his garage, which was full of tools, and we made a go-kart and a jewelry box from the wood lying around. We threw spaghetti on the ceiling to see if it was cooked. I got a job when I was fifteen and bought a car with my earnings, which he taught me to drive. He showed me how to change the brakes and check the oil.”

As she grew, her relationship with her father became more complicated. “As I got older, the positive, tangible things he was passing on to me started to become eclipsed by lessons that were emotionally challenging,” she admits. “I was learning that I couldn’t rely on him to show up when he said he would and that he wasn’t paying child support.

“I learned that it wasn’t safe to get in a car with him even when he said he hadn’t been drinking, because, more often than not, he was lying. I stopped visiting him at home. We would meet for sushi dinners instead, but he would still drink too much. I switched to breakfasts, but he’d be drunk when he arrived at 9 A.M.

“I saved money for a year and went to Europe when I was eighteen. When I got back he told me that while I was away he had driven my little car (without a licence) and crashed it. I was learning that, for my dad, alcohol came first. We grew apart.”

Two years ago, the photographer was not in regular touch with her father anymore. She had not spoken to him for about a year, and she did not know where he was living. She expected that someday she would receive a phone call with bad news, and that call came in late 2017: her dad had passed away from an accidental drug overdose.

“After he died, I found out he had been evicted from the apartment he had been living in for over twenty years and was placed in a single room occupancy hotel (SRO),” she recalls. “SROs can be really tough places to live in and are generally unkempt and falling apart.

“Honestly, the thing that haunts me the most is the fact that my dad didn’t have a bed, but was sleeping on the floor in the middle of a room that was maybe 10×10 feet, with his food packed in Tupperware around him.

“The other thing that I always think back to was that both the T.V. and the radio were on, and that was very much like my dad.”

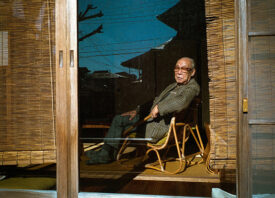

In the wake of the tragedy, Dives did what she had done as a child: she started to make things with her hands. Instead of a toolbox and an engine, she used her camera. She returned once to the SRO while she still could. “Even though it was a bit weird, I knew I would regret not taking photographs of it,” she remembers.

Even after she moved on from the room and someone new moved in, she continued to take pictures. Instead of interiors, she photographed anything that reminded her of her father, creating layered double exposures over several months.

“I would get on my bike and ride around the neighbourhoods where I grew up or where we would go when I was a kid,” she tells me. She also photographed her father’s body at the funeral home.

The decision to transition into double exposures was an instinctual one, but it also mirrored her experience with grief and the fracturing effect it had on her everyday life. “Creating double exposures was the perfect way to express my confused, messy, contradicting, and fraught feelings,” Dives explains.

“Losing him to a drug overdose has made me feel like the positive memories are in jeopardy and I have to protect them somehow,” the photographer continues. “Because his death is entrenched in stigma that perpetuates the idea that someone who uses drugs is less worthy of life, and therefore less worthy of remembering, I have to stand up for him and explain that he was more than his drug use.

“I have to justify his goodness, instead of simply mourning the loss of my father. Taking these photographs has been a way for me to reconnect with him and remember him in his complexity instead of just his faults.”

For Dives, the double exposures became a way of representing how she felt, but perhaps they also represent a kind of collaboration between a daughter and her father. There’s something of each of them in every frame: it was his room, but they’re her memories.

“I knew the project was coming to an end when I began photographing things with only one exposure again,” the artist says. “I think I was intuitively, through my photo-taking process, healing from the experience, and as I became more healed, my photos of once again returned to single exposures.”

Dives and her father might not have spoken in the year leading up to his death, but in these photos and the subliminal space they occupy, they do cross paths–again and again.

Jackie Dives is based between Vancouver and Toronto. You can find more of her work by visiting her website and following along on Instagram at @jackiedivesphoto.

All images © Jackie Dives