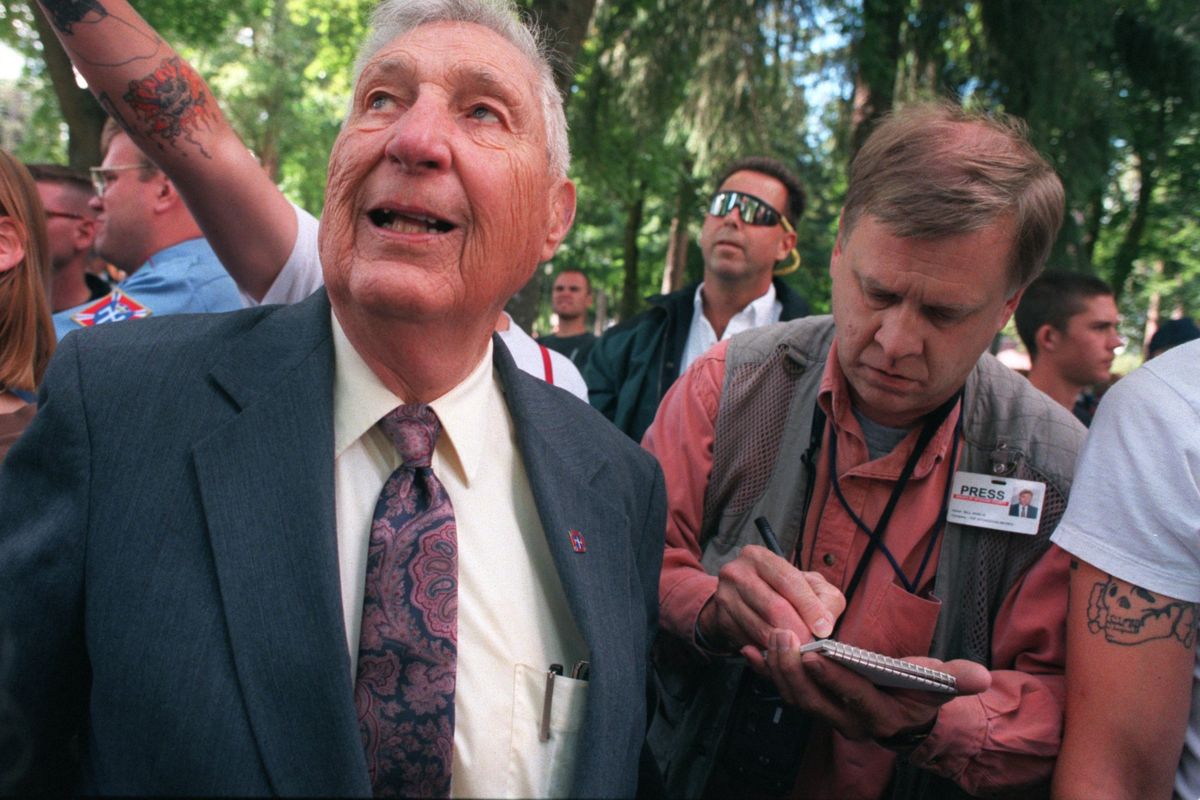

Spokane Daily Chronicle, Spokesman-Review reporter Bill Morlin, ‘a journalism giant,’ dies at 75

Bill Morlin, the dogged investigative reporter who covered everything from neo-Nazis and white supremacists to crooks and corrupt politicians in some four decades at the Spokane newspapers, died Saturday. He was 75.

A third-generation Spokanite born and raised in Peaceful Valley, Morlin combined a native’s knowledge of his community with a vast array of sources to break an amazing string of stories in his newspaper career, first at the Spokane Daily Chronicle and later at The Spokesman-Review after the papers’ staffs were merged in 1983.

Bill Morlin, Jess Walter and Shawn Vestal discuss Ruby Ridge for a podcast, Aug. 15, 2017, in Spokane, Wash. Dan Pelle/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW (Dan Pelle/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

“He was a Spokane kid who wanted to be an investigative reporter,” said Chuck Rehberg, a former newspaper executive who served as Morlin’s editor at one point on the Chronicle. Newspaper managers tried to move Morlin into an editor’s slot at one point, but he resisted.

“He wanted to be out there, mixing it up,” Rehberg said.

He always wanted to be a reporter, his wife Connie Morlin said.

As a youngster in Peaceful Valley, Morlin had three newspaper routes. He even produced a neighborhood newspaper with a set of letters and an inkpad that could be used as stamps, and made his sister and her friends deliver the finished products. He was the editor of the Eastern Washington University newspaper in college, and an intern for the Associated Press before coming to work at the Chronicle.

Karen Dorn Steele, who would later partner with Morlin on an investigation into Spokane Mayor Jim West’s use of city computers to search gay dating sites, said she first met Morlin through the local chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists when she was a reporter at KSPS-TV.

“I just really respected his work,” Dorn Steele said. “Behind his aggressive reporting style, he really cared about justice and people and journalism.”

“He was just a giant in the field of journalism,” said Tony Stewart, a retired professor at North Idaho College who helped form the Kootenai County Task Force on Human Relations to counter the presence of the Aryan Nations in the region. “I have such admiration for his work. I have never known a print reporter who had as much knowledge of hate groups.”

In the early 1980s, Morlin began writing about the Aryan Nations and its leader, Richard Butler, at a compound north of Hayden Lake. At the time, many regarded the group as a few crazy people who occasionally dressed up in uniforms to gather in parks or parade in the streets, and wanted to downplay their presence in an area trying to establish its tourism business.

“He never bought into that,” Stewart said, adding he and Morlin would tell people that ignoring Nazis didn’t work in Germany either. “He knew the danger of it all.”

Over the years, the Aryan Nations compound became a magnet for white supremacists, some of whom would spin off to form their own groups that committed murders and robberies. Morlin would keep track and chronicle their activities, including the bombing of the newspaper’s Spokane Valley office and a Planned Parenthood office by a group that called itself the Phineas Priesthood. The bombings were designed to distract law enforcement for bank robberies committed elsewhere shortly afterward.

Morlin led the newspaper’s coverage of the siege at North Idaho’s Ruby Ridge between federal law enforcement agents and Randy Weaver. He became a national expert, the go-to reporter for information on white supremacists and other hate groups because of his contacts with local, state and federal law enforcement.

At one point, he was so tapped in to federal law enforcement that he had a “scoop” his editors wouldn’t print. After the Alfred Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City was bombed on April 19, 1995, Morlin began “working the phones” and developed a story that people involved with right-wing militias were suspected of carrying out the bombing.

The national wires were reporting the prime suspects were Islamic extremists. The Spokesman-Review’s editors held Morlin’s story, and the next day’s front page carried a wire story that quoted an official FBI communiqué that the agency was “currently inclined to suspect the Islamic Jihad as the likely group.”

Two days later, Timothy McVeigh and two others with ties to militia groups were arrested for the bombing.

“He was a real journalist – the old-fashioned kind. He really worked hard to get to the hard news,” said Dan McComb, a former photographer for The Spokesman-Review.

McComb first met the newspaper’s senior investigative reporter after he had been at the newspaper for about six months and was pulled off an assignment of photographing kids at the Eagles Ice Arena with instructions to meet Morlin at the airport.

Morlin had a tip that Mark Fuhrman, the Los Angeles police detective who was a key witness in the O.J. Simpson murder trial, was there. As McComb approached, Morlin told him to be quiet and wait while Fuhrman checked in. He went up the concourse and eventually Morlin approached Fuhrman for an interview. After they talked, Fuhrman walked up the concourse toward McComb, who was taking photos. As the detective got close, he hit McComb with his briefcase, knocking the photographer to the ground and continued hitting; McComb continued to shoot photos.

Fuhrman was reportedly angry that McComb’s photos might also show his wife, who was accompanying him. Morlin ran up, dialed the newspaper’s editor and handed Fuhrman the phone. After a brief conversation, the attack stopped. The photo that accompanied the next day’s story about the Fuhrmans shopping for a home in North Idaho showed the detective striking at McComb but did not show his wife.

The two would later work together on stories about right-wing militias that allowed the pair to witness their training in the Inland Northwest forests. “Bill found ways to get people who would not want to reveal things to reveal them to him,” McComb said.

Morlin wrote about Spokane’s Gypsy community and its clash with city law enforcement and prosecutors over a police raid. He broke stories on a wide range of legal topics, from bodies that were allowed to decompose at a local funeral home to a “diploma mill” operating in the Spokane area that provided phony degrees to customers willing to pay its fees.

The mill’s mastermind, Dixie Randock, was eventually convicted of mail and wire fraud and sentenced to three years in prison. The newspaper traced people in government, academia and law enforcement who used the fake degrees as part of their resumes and produced a searchable database with thousands of the diploma mills’ customers.

In 2005, he teamed with Dorn Steele on an investigation into then-Mayor Jim West and reports of past sexual abuse and allegations that he used city computers to meet young gay men on an internet dating site. West, who at the time was one of Spokane’s most successful politicians, was later recalled in a special election.

Morlin had worked on the story – “following threads,” Dorn Steele said – for years. But it was so sensitive that in the months before the story was ready for publication the two reporters were moved out of the newsroom while they were researching it.

Dorn Steele said she respected Morlin’s ability to get to the bottom of things.

“He could keep contact with all kinds of sources – cops, prosecutors, white supremacists,” she said. “He was thorough and aggressive and fair.”

The two retired from the newspaper on April 1, 2009, but Morlin kept working. The next day he started his own company, Morlin Investigations, and did research for local attorneys. He also wrote about hate groups for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hate Watch and Intelligence Report, was a stringer for the New York Times and was a guest lecturer for college journalism classes.

“He was very engaged and very involved,” his wife, Connie Morlin, said Sunday. He recently had heard from two sources, one a former FBI agent and the other a former police officer with information about two unsolved crimes and was “fired up” about two possible stories.

Beyond journalism, he was a woodworker, carpenter and furniture builder, and a railroad enthusiast who kept building on his model trains. He developed a love for trains while watching them cross the bridge visible from their home in Peaceful Valley, she said. He was an avid skier who was proud that he taught his granddaughter to ski.

Although people who knew Bill knew the Rolling Stones were his favorite band, Connie Morlin said his taste in music was so eclectic that he kept up with current artists and sometimes introduced his grandchildren to new bands.

He was hospitalized in the Sacred Heart Medical Center Intensive Care Unit with a gall bladder infection about a week ago and on Saturday succumbed to sepsis. But he was in good spirits until the end, and at one point asked his wife to get out a notebook and write down some things he needed to tell her.

Along with his wife, he is survived by son Scott Morlin of Spokane, his wife Jaimie and their daughters; son Jeff Morlin, also of Spokane, his daughter and stepson; and a sister, Ann Morlin, also of Spokane.

Plans for a memorial service are pending.