Happy Inventors’ Day! That is, Happy Inventors’ Day if you’re in the United States. Plenty of other countries celebrate Inventors’ Day, but — perhaps to make the most of local inventiveness — it’s a different day depending on what country you’re in.

The Inventors’ Day in the US is on February 11, mostly because it’s also Thomas Edison’s birthday. In this country, he’s the poster boy of inventions. He registered over 1,000 patents, and managed to get credited for the electric incandescent light bulb and the movie camera. You could argue about Edison’s originality in any or all of those inventions, because really what he did in those cases was refine ideas that already existed until they were more generally useful. But that’s actually what most patents are; refinements. But Edison also invented the phonograph, which was pretty unique and didn’t have any prior art.

It’s the accumulation of patents that established Edison’s reputation as an inventor. He was an entrepreneur and a businessman — maybe more so than an inventor, in fact — who founded 14 companies, including a big one you may have heard of, General Electric. But he was also a nonstop experimenter.

He worked as a telegraph operator early in his life — starting in his early teens, in fact — and was working at Western Union in 1867 when he was experimenting with electricity. He was working with a lead-acid battery that leaked acid onto the floor. Buildings in 1867 were not what you’d call “up to code”, and the acid dripped down into the next level. Unfortunately for Edison, the next level was where his boss’s office was. The acid dripped right onto that man’s desk, and the next morning Edison was looking for a new job. But on the other hand, it might have been a stroke of luck for him. Freed of the constraints of going to work, he received his very first patent not long after, for an electric machine to record votes.

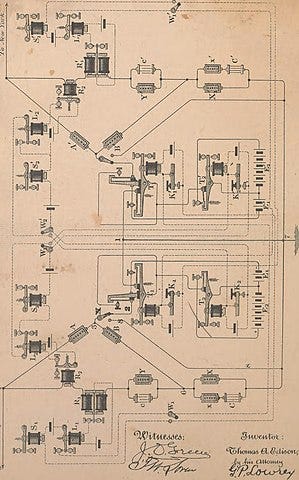

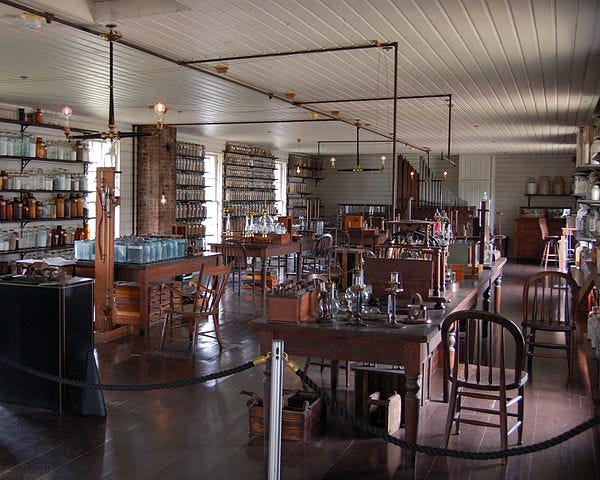

Not too long after that, Edison patented the “quadruplex telegraph.” It’s another example of his refinement of an existing idea. Telegraphs already existed, but his system doubled the messaging capacity of a single telegraph wire. He sold it to Western Union for $10,000 (he had expected them to offer only half of that). He used the money to fund what might have been his greatest invention: the research lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey. As far as anybody know, it was the first “industrial laboratory.” He hired people to conduct exhaustively detailed experiments at his direction. Anything patentable was submitted under Edison’s name — and that’s where his 1,093 patents came from.

But Edison didn’t patent every invention. There was a solar eclipse in 1878, and he came up with a device to measure infrared radiation so he could study to solar corona. He named the thing a tasimiter, and didn’t apply for a patent because he couldn’t think of any reason people would want to buy one.

That’s the key to patents. They have the image of innovation, but really a patent is a legal and economic thing, and doesn’t have much to do with originality. A patent is a license to exclusivity. If you have a patent on some device (you can’t patent just an idea), you can sell versions of it, and (at least theoretically) stop anybody else from competing with you. A patent doesn’t mean you had an idea that nobody ever had before. It just means you filed the paperwork first, and your idea is different enough from other similar ones.

Different enough is a value judgment, and patents are based on those judgments, made by the patent examiners. In the country, that is, where you applied for your patent. Because a patent is a legal instrument, so it’s valid only within the legal framework — the country — where it’s granted. If you patent a supergadget in the US, that doesn’t prevent somebody in a different country from making supergadgets (okay, there are treaties, but we’re dealing in generalities here). The real point is that invention, which is what patents are all about, is very much restricted to arbitrary political boundaries. Countries. And that’s why Inventors’ Day is celebrated in a lot of different countries, but on different days.

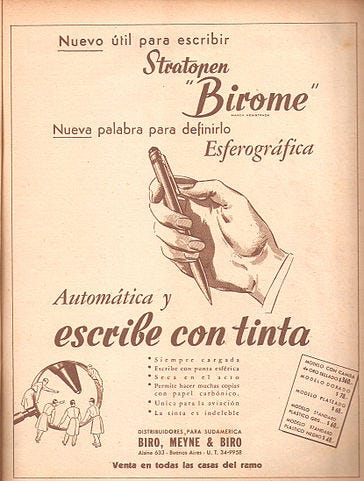

In Argentina, Inventors’ Day is celebrated on September 29. That’s because it’s tied to the birthday of a famous inventor from that country: László József Bíró. His invention portfolio? The ballpoint pen. Now, over in Hungary, they don’t care about Bíró, even though I’m sure ballpoint pens are as popular there as they are everywhere else. Nope, in Hungary, Inventors’ Day is on June 13. That’s because of the Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi, who isolated Vitamin C and won a Nobel Prize. June 13 isn’t his birthday, though; it’s the day he registered his patent (valid in Hungary) for synthetic Vitamin C.

Thailand celebrates Inventors’ Day too, but on February 2. The national inventor and patent in this case are King Bhumibol Adulyadej and the patent for a slow speed surface aerator. I’m not entirely sure what it does, but it’s something to do with purifying waste water.

We put a lot of credence into patents, and when somebody has one, or several, it just feels like they’re more creative and innovative that the average person. That might be tied into the old idea that things like inventions and scientific discoveries are the singular creations of individual geniuses. But that notion — which you could call the “heroic theory,” because it’s all about individual “heroes” — doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny. Most inventions, at least if you think of “inventions” as “things that get patented,” are refinements of other inventions. Edison didn’t invent the “electric light bulb”; he just came up with a longer-lasting filament tied to a whole system of electric power generation. The incandescent light bulb had been around for over a century before Edison.

As for scientific and mathematical discoveries, neither of which can be patented, the general rule seems to be that a number of people in a field are thinking about the same problem at the same time, and more than one of them comes up with a solution. Take calculus — that’s a legitimate mathematical discovery, and it was invented by Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, completely independently of each other, at roughly the same time. Analytic geometry is another of those — it came later, because you need calculus first — and both René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat came up with it. Neither was aware of the other’s work.

This is not to say that there aren’t real geniuses. They certainly exist, and there are probably a lot more of them than we ever find out about. In fact, R. Buckminster Fuller — who was himself recognized as a genius by at least some people — once said something like “everyone is born a genius, but the process of living de-geniuses them.” So try not to be de-geniused! But don’t measure your genius by patents. That’s another thing altogether.