How a Christian epidemiologist works to sway white evangelicals on COVID and vaccines

Emily Smith, an epidemiologist married to a preacher, has been able to reach evangelicals in a way others can’t, by meeting them where they are.

Listen 11:39

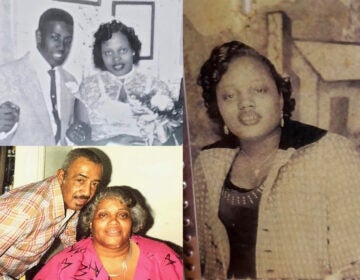

Emily Smith, an epidemiologist married to a preacher, has been able to reach evangelicals in a way others can’t, by meeting them where they are. (Courtesy of Emily Smith)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

How do you talk to people who don’t trust you?

Lots of public health officials have struggled with this question over the past year as they’ve tried to reach people who don’t think they should be vaccinated, or who don’t even believe the coronavirus pandemic is that big of a deal to begin with.

One group that public health officials have had particular trouble reaching has been white evangelical Christians. A recent poll found that among white evangelicals, 45% said they would not get vaccinated.

Emily Smith, an epidemiologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, says it’s imperative that this population gets vaccinated.

“The white evangelical group is a good proportion of the U.S. population. We have some work to do to get the message out, to get more of them … to reach herd immunity.”

Smith’s approach to epidemiology and public health messaging is a little different than most. She’s a woman of science and religion. She doesn’t see those two fields as that different.

“I’m also in the buckle of the Bible Belt here in Texas, married to a Baptist pastor,” Smith said. “I got into epidemiology because I see it as a story of the Good Samaritan, of quantifying who is most in need for any disease or health disparity and choosing not to walk by.”

She started breaking down scientific information for people early on in the pandemic, through her blog and Facebook page, Friendly Neighbor Epidemiologist.

“I really try to keep the friendly, the neighborly part,” she said. “You know, if I could talk with people in real life, I would probably have you at my kitchen table with cookies. That’s just my personality.”

Smith gets millions of visitors every month across platforms, a lot of them white evangelical Christians. Early on, she would answer questions such as “Can we go to church?” “Can we have a BBQ?” or “Should we wear masks?”

“At the very beginning … all of us had this sense of solidarity,” she said. “Flattening the curve, protect[ing] our neighbors, protect[ing] our health care workers, including in the church space.”

A politicized pandemic

But over time, the rhetoric changed, she said. There was a split between faith and science.

“The split happened because of the political ideologies that happened in 2020. And I get in trouble every time I talk about this because some will say, ‘Don’t bring politics into it,’ but you have to bring politics into it to see where the rhetoric happened.”

The more politicized the pandemic became, the more misinformation and disinformation Smith had to fight. She had to start debunking anti-science sentiments: people calling the virus a hoax, saying that masking was a sign of fear, that the vaccine was a “mark of the beast” or that it would ruin our immune systems.

“Those were only coming from faith spaces, and at the beginning it was far-right spaces,” Smith said. “Those have become a little bit more mainstream now. It all became this one messy thread of faith over fear. And I’m really trying to do my educational work to let [white evangelicals] see that the same people who were saying, `faith over fear,’ those groups have really infused this ‘global domination,’ ‘mark of the beast,’ ‘vaccines are going to ruin our immune system over time’ [rhetoric].”

Subscribe to The Pulse

She said it’s hard to get people to recognize this — and to recognize that sometimes there are some contradictions with these talking points.

“You know, they’re good people sharing really awful anti-science stuff, thinking that it’s truth. So there’s a lot of work to debunk what they don’t know that they’re actually reading right now.”

Smith finds the whole “mark of the beast” comparison especially worrying. You may have heard it before: It’s a biblical reference that has become wrapped up in conspiracy theories.

“The mark of the beast, from a Christian faith perspective, is something in Revelations,” Smith said. “It is supposed to be a mark in the end times. And the Christian space has heard theories on what the mark of the beast is for decades and decades and decades. … The latest one is a conspiracy theory about the vaccines or masks being mark of the beast. And it is just, it’s a warped way of viewing something that’s actually lifesaving as a mark towards something that is anti-Christian or anti-faith.”

Smith said, in terms of vaccine attitudes, it’s a spectrum: Some people don’t buy into these hoaxes and are just trying to wait and see. Maybe they’re a little nervous about the vaccine, and the seemingly new technology that allowed for their quick development.

But overall, she said, anti-vaccine sentiments are growing in this group, and it is something we should all be worried about.

“What is happening, though, is that a lot of the anti-science, anti-vax groups are now infusing this new vaccine hesitancy group in really sneaky ways.”

The message

Smith said the key in getting the right information to this group may lie in not only the message, but the messenger. And as the wife of a minister, as well as a Christian, and a scientist herself, she hopes that she might be more trusted among this group.

“I do think that that helps let people know that I’m just a real person,” she said. “I’ve got two children. I understand the church world from an evangelical perspective. I do think that that helps build some trust that … when I talk about science and wearing a mask and love for [my] neighbor, I don’t have a propaganda, or an agenda that is anti-faith.”

She said faith and science can be informed, and that trying to get people to recognize how they can both work with each other during the pandemic has helped. That it has helped people trust what she is saying and where she is coming from.

But she said an important factor in the success of her work has to do with tailoring her message — something that she said she does naturally. Take, for example, how she talks to other moms:

“When we were talking about schools, I talked about what I would do with my children. ‘What about playing with friends on the playground?’ Here’s what I’m doing with my kids, and really, that’s what I was telling my friends. I just wrote it down in a post.”

Smith said she’s gotten some pushback for this work. On Facebook, you might see the usual mean-ish comments, such as, “Why is it your business if I’m wearing a mask?”

But the comments get way worse sometimes, she said, such as when she writes about things like health disparities. She’s even gotten some death threats.

“That is new for me. I mean, I’m a scientist pastor’s wife. You know, you’re not really trained to figure out how to deal with that,” she said. “Those are very scary. And, you know, just some really nasty stuff about blaming immigrants, racial disparities, when I write on that, there’s always threats and messages that come. And I’m a mom, that’s scary for my kids.”

Although she gets those online threats, Smith said she’s still committed to doing this work.

“I just feel such a sense of obligation, especially from a Christian perspective, to be the Good Samaritan, and hopefully get people to band together and still wear their mask and get a vaccine.”

She says that although the job can be tough at times, it can also be inspiring.

“When I get [comments] from moms that are just like me,” she said. “And they heard different things, maybe from their friends or their pastors, that were not correct … And they went and got their vaccines and then they send pictures of [them] being able to hug their parents that they hadn’t seen in a year, that just means the world to me. That they trusted me enough to do that, that they could connect with their families.”

Emily Smith is an epidemiologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. On social media, she’s parsing out health info as “Friendly Neighbor Epidemiologist.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.